It is a rainy day in Suleymaniye, one of the seven historic hills of Istanbul, where the area’s famous mosque was finished in 1557 after seven years of construction.

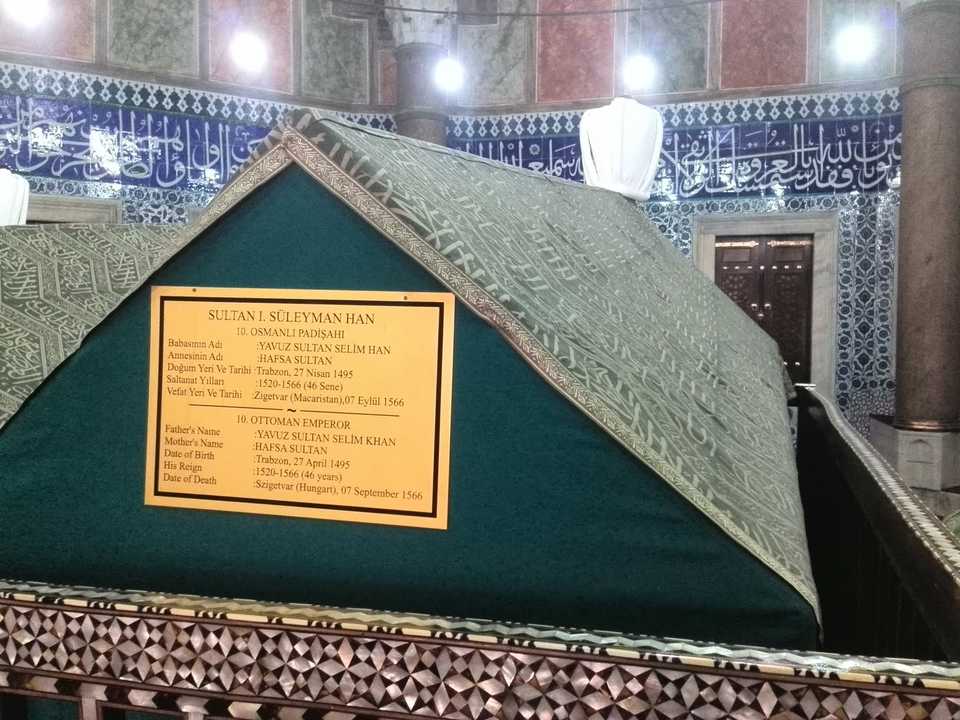

Many unique features distinguish the mosque and its complex, which until last century included several university colleges (madrasas), a hospital, a hamam, a charity foundation and its cemetery – alongside Sultan Sulayman’s tomb.

Most of these facilities are lost, but one still remains and gives tranquillity to visitors passing through the yard of the mosque complex – the cemetery.

The rows of tombs are located at the front of the complex so that they can be seen as a lesson on the importance of death by those praying inside. The graves serve as a reminder that man is mortal and that his presence on Earth is temporary.

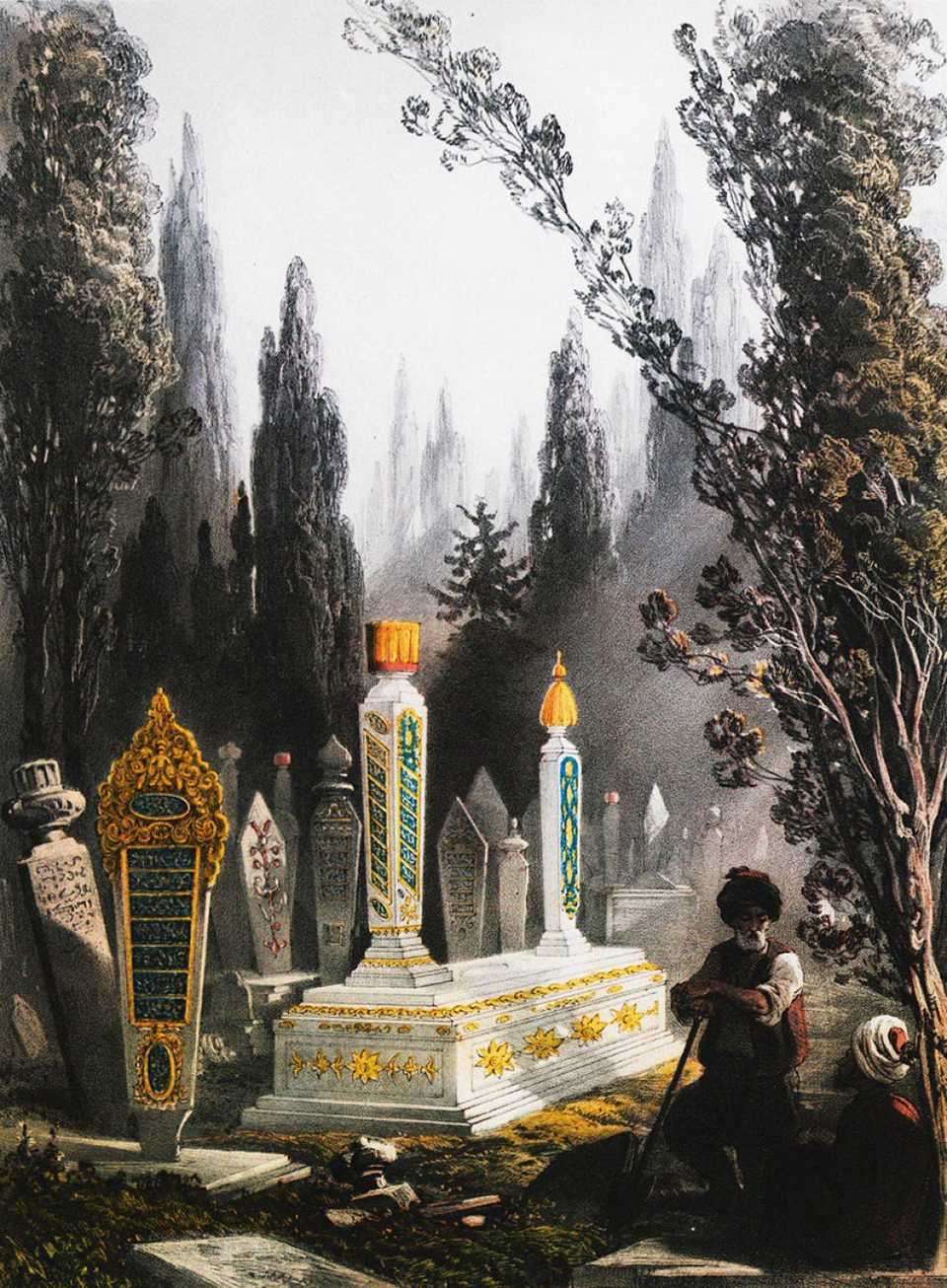

But they also serve to preserve the artistic interest the Ottomans had in gravestones.

“The Ottomans had a cemetery and tombstone art culture. Some cemeteries are at a mosque yard, others in the middle of a neighbourhood,” Associate Professor Suleyman Berk Associate Professor at Yalova University and expert in Islamic-Turkish Arts History tells TRT World.

More significantly, he explains that every tombstone is unique in its characteristics and story.

“It represents the biography of the deceased person”.

One tomb shows the graveyard of the naval captain (Kaptan-ı Derya) Ibrahim Pasha, who passed away in 1725.

According to the historian Talha Ugurluel, this tomb shows a captain with an anchor, rope, and broken mast who enters the ship that takes him to the afterlife, his final resting place.

The ancient tomb with two stones, belongs to the young woman Fatma Müşerref Hanım from Thessaloniki. She passed away when she was engaged, why on the left gravestone is a bridal dress.

On the right tombstone of the same grave is a broken rosebud, marking the death of a female family member. The tomb was built by her father, Mustafa Fevzi Bey.

The graves of different Sufi orders and their dervishes are also distinguished with different coloured cloth and head coverings.

Their symbols have been appended to their gravestones. For instance, this man was a dervish from the Bektashi order.

People of knowledge and sultans

“The reality of death was seen as a form of balance in life…in our culture graves have a high value. One prays for the deceased when one passes cemeteries and graves. The special thing about gravestones from the Ottoman period is their aesthetic character. Cemeteries have a lively atmosphere,” tells us Ass. Prof. Suleyman Berk.

Some gravestones have different colours to depict details of the person’s life. For instance, green was a common colour used by scholars and leading intellectuals in science.

Artists graves are marked with their occupation. Writers with books, pencils, and paper.

Ottoman sultans don’t have gravestones, but instead have their own tombs. The turban or fes they wore was put on the top of their tombs.

These “spiritual resting gardens” created by Ottoman society were designed to memorialise the deceased as well as the culture they inhabited. They can still be experienced today, especially in Istanbul.

Discussion about this post