Working in a ward full of patients possibly infected with the deadly coronavirus is like surviving in a war zone. That is how Yusuf Ali Altunci, a 43-year-old emergency medicine specialist from Turkey’s third-largest city Izmir, described the situation of frontline doctors tackling the Covid-19 cases.

“It’s like there is someone firing into the crowd and you are trying to survive without getting caught by the bullets,” Altunci told TRT World.

So far, the pandemic has claimed 168 lives and about 10,827 of 76,981 people who have been tested for the coronavirus have tested positive, according to the Turkish Ministry of Health.

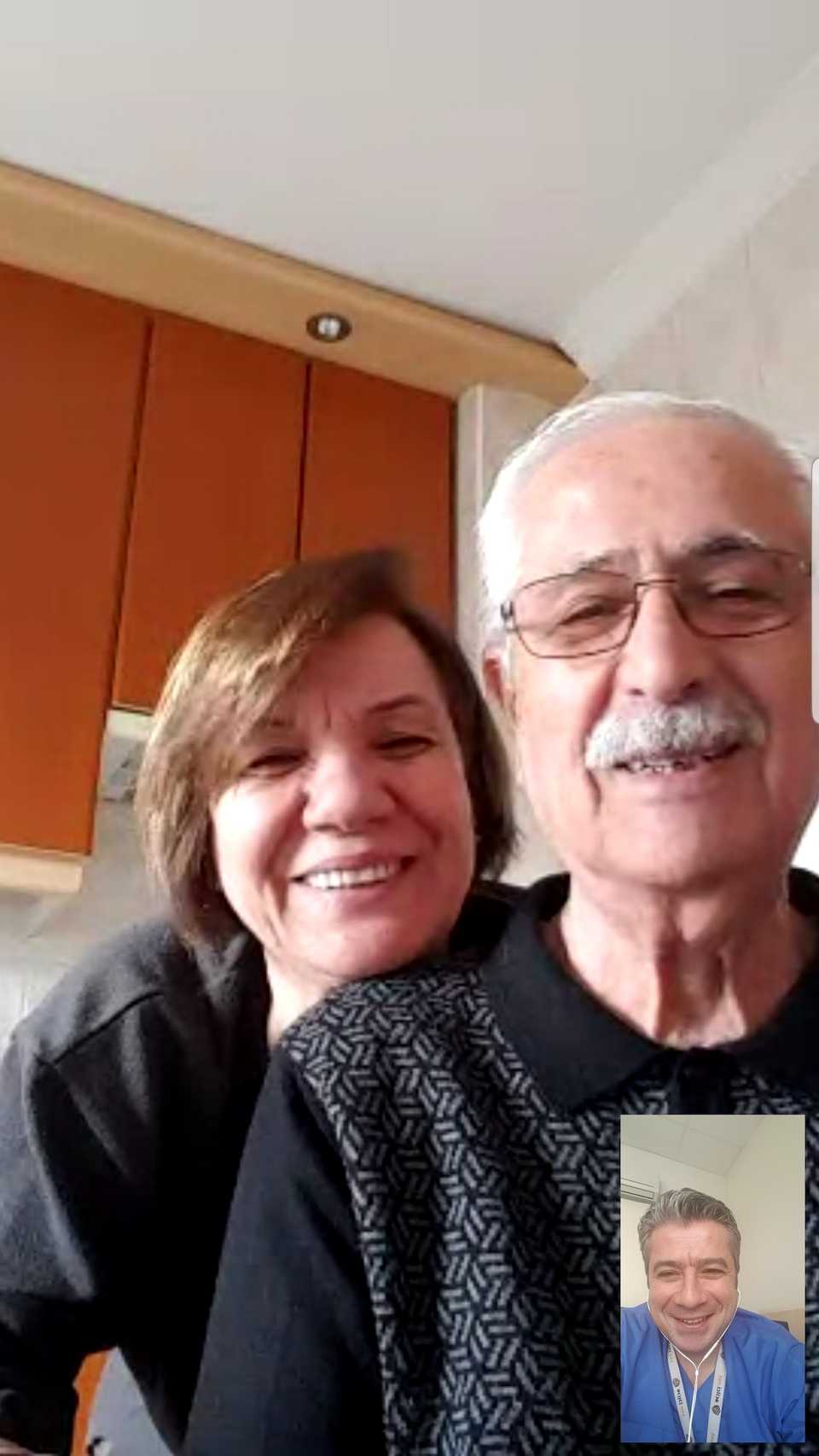

In his 18 years of professional life, Altunci has never been physically so distant from his parents. Ever since Turkey declared a medical emergency earlier this month, he hasn’t visited his elderly father and mother, who live just a few kilometres away from his house.

Things haven’t been the same with his family either. “I do not touch my children like I used to before. I try to touch them as little as possible. Every time I try to hold them, I feel nervous,” he said.

“As a father, I find it hard to keep distance with my children. And my kids worry for me. That’s upsetting me the most.”

To cope with mental and professional challenges — from examining patients to ensuring all the logistics are in place — Altunci said he and his colleagues are having frequent meetings to update each other about the patient inflow and other needs that arise while dealing with the Covid-19 infected patients.

“We feel mentally relaxed after making plans and discussing alternatives,” he said.

Altunci is dreading the time that he or any of his colleagues catch the virus while treating the patients. Although there are no positive cases among health workers associated with his hospital, he said it would be ‘quite traumatic’ to connect one of their own to the respirator.

Working in a pandemic has a physical toll on doctors as well. For instance, wearing protective gear — glasses, gloves, masks — for a 10-12 hour shift brings a lot of pain and discomfort. When the patient inflow increases, they cannot remove their suits for even a glass of water or a bathroom break.

“It is so hard to breathe wearing a mask all day long and to be exposed to the smell of disinfectants all the time,” Altunci said.

Altunci knows that they are in it for the long haul, so he’s considering turning his office in the hospital into a private room, where he can sleep, eat and change his clothes.

“If necessary, I will live in the hospital for a while,” he said. “Some doctors who live with children and elderly parents have already rented out a house together or moved in with their single friends.”

“So there are a lot of children who are going to bed without their fathers telling them fairy tales. But it’s our job. We can’t let fatigue or other pressures discourage us. Our biggest motivation is when patients look into our eyes with a mix of anxiety and hope. That keeps us going.”

Discussion about this post