In 1502, Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II sought to commission a bridge project across the Golden Horn connecting medieval Istanbul to Galata.

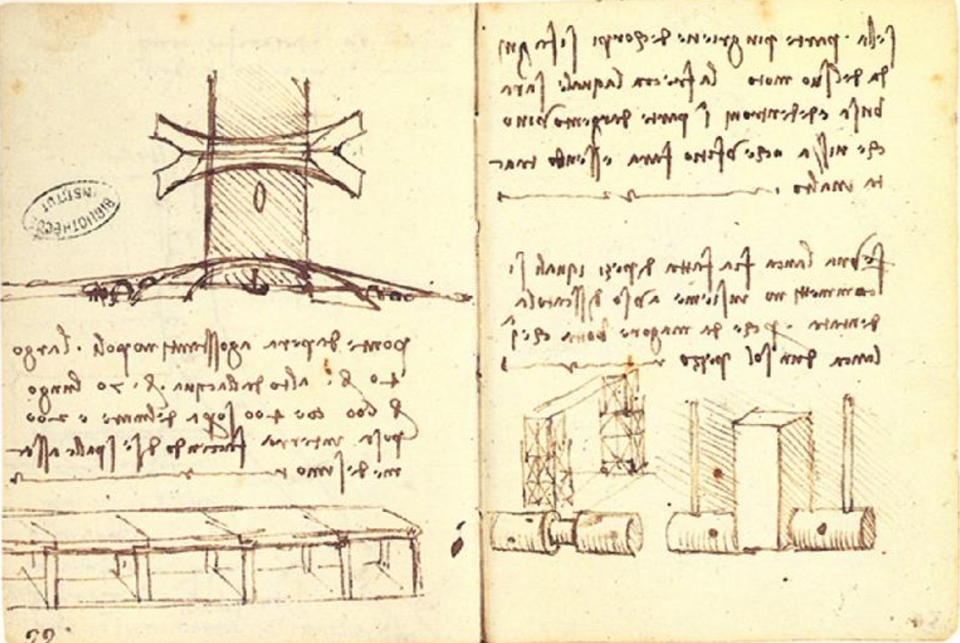

The Renaissance painter and inventor, Leonardo Da Vinci, spelled out his pitch for the contract in a letter sent to the emperor.

Now more than 500 years later, engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have tested the great Italian’s designs and have concluded the structure would have been structurally sound.

Graduate student Karly Bast, undergraduate Michelle Xie, and Professor of Architecture, John Ochsendorf, released the results of their research in October.

The team took into consideration the materials that would have been available and used at the time, construction methods, and geological conditions at the Golden Horn. Da Vinci’s bridge would have stood without mortars and fasteners within its stones to support it.

In ordinary long bridges from the period, semi-circular arches and piers were used along the length of the structure to maintain its structural integrity. However, the Italian proposed a single arch spanning the waterway, which would have rose to 43 metres above sea level and would have been 240 metres long. The specifications would allow boats to pass under the bridge with ease.

To prevent a collapse of the bridge, Da Vinci aimed to include parabolic abutments on both sides of the structure.

What inspired Da Vinci

Physics Professor Bulent Atalay, the author of Math and the Mona Lisa: The Art and Science of Leonardo da Vinci, spoke to TRT World about the Italian artist’s idea for the famed Ottoman capital.

After French troops invaded Milan in 1499, Da Vinci fled Milan with his assistant Francesco Melzi and his mathematician friend, Luca Paccioli. The trio eventually settled upon Venice, where they came into contact with Ottoman Turkish merchants.

The merchants informed the Italian that Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II was looking for an engineer who could construct a bridge over Halic, the Turkish name for the Golden Horn.

On their advice, Da Vinci sent a letter to the Ottoman monarch spelling out his designs. A copy of the correspondence was discovered in the Topkapi Palace archives in 1952. Ottoman officials, however, mistakenly attributed the note to a ‘Ricardo of Genoa’.

“He opens his letter with the usual refrain then spells out his interest in coming to Istanbul,” Atalay recounts.

“In his own notes, he always wrote in Italian from right-to-left (in ‘mirror script’), and on this occasion, he actually wrote a letter in Turkish in the ‘Arabic Style’ from right-to-left,” Atalay said.

“I, your faithful servant, understand that it has been your intention to erect a bridge from Galata (Pera) to Stambul… across the Golden Horn, but this has not been done because there were no experts available. I, your subject, have determined how to build the bridge. It will be a masonry bridge as high as a building, and even tall ships will be able to sail under it,” the letter said.

But the Italian’s ambitions did not end there, as he also proposed to build a further bridge connecting Europe and Asia, across the Bosphorus Strait.

“I plan to build a suspension bridge across the Bosporus to allow people to travel between Europe and Asia. By the power of God, I hope you will believe my words. I will be at your beck and call at all times,” he adds, signing the letter “Architect/engineer Leonardo da Vinci.”

At the time, the ideas were revolutionary, as no bridges existed along the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus. The first suspension bridges would not be built until 400 years after the letter, in the 20th century.

Other ideas Da Vinci floated, including a gristmill powered by wind, which used a bilge pump to expel water.

“I also paint,” Da Vinci added, according to Atalay.

However, despite his clear enthusiasm, the Ottomans did not hire the great artist and for hundreds of years, the letter was lost.

Why there was no response, remains a mystery.

“In the early 20th century, the sketch of a bridge appears in one of Leonardo’s notebooks in a royal library in France,” Atalay added.

A replica of that bridge was built in 2001 by the artist Vebjorn Sand in the Norwegian town of As.

That one was only a scaled version, one third of the size that the one in Halic would have been.

Nevertheless, the Norwegian structure, gives a glimpse of what could have been another of Istanbul’s magnificent architectural masterpieces.

Discussion about this post