Turkey has the largest ethnically Kurdish population in the region, numbering nearly 15 million of its population. And their vote will play a crucial role in Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections on June 24. Kurdish votes, predominantly shared between Justice and Development (AK) Party and People’s Democratic Party (HDP), have shaped election results in recent elections.

Huseyin Alptekin, an assistant professor of political science and international relations at Istanbul Sehir University, said, “Of course Kurdish votes play a key role for upcoming elections. So far, Kurdish votes in Turkey have two specific addresses. They go to AK Party or to the HDP.”

In the southeastern cities of Turkey, where the AK Party and the HDP receive almost all the votes, Kurds are the majority of the population.

Journalist and writer Nevzat Bingol, deputy chairman of the New Middle East Strategic Research Center (YORSAM), said, it’s not only the southeastern cities that matter, “Kurdish votes are not limited to the provinces that are predominantly Kurdish populated. There are about 6-10 percent conservative Kurdish voters who vote for the AK Party in metropoles.”

YORSAM is based in Diyarbakir, a predominantly Kurdish city in southeastern Turkey.

The Kurdish society in Turkey express themselves in various ways, depending on their priorities: Sunni and religious Kurds identify themselves as Muslims, as the Kurdish identity comes first for the secular and left-wing ones. Alawites mostly identify themselves as Turkish citizens, not prioritising their ethnic roots.

The conservatives are to be targeted to gain support in the upcoming elections by the AK Party and the HDP, due to their swing votes.

On the path to the parliamentary elections, the AK Party, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and another nationalist party, the BBP, have built an electoral alliance named the People’s Alliance. Meanwhile, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Iyi (Good) Party, the Saadet (Felicity) Party and the Democrat party have formed the Nation’s Alliance.

All the parties in the People’s Alliance support the same candidate for the presidential elections as well: incumbent president and AK Party leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Efforts to put opposition parties, along with the HDP, together under a joint presidential candidate, who was discussed to be the former president Abdullah Gul, had collapsed before they formed the Nation’s Alliance. Since each party in the alliance has its own presidential candidate, they will only run in the parliamentary elections together. The HDP is running in the elections independently, its presidential candidate is the former co-chair Selahattin Demirtas.

Looking at the former choices of the Kurdish voters, there are two possible scenarios: One is to vote for the AK Party’s alliance with Turkish nationalist parties and the other one is to vote for the HDP, which has its presidential candidate and many members in jail on accusation for their links to the PKK terror group.

PKK is a designated terror organisation by Turkey, the US and the EU. It has been fighting the Turkish state for more than 30 years and left more than 40,000 dead, including civilians. Their attacks mostly targeted the security forces in the southeast of the country.

HDP is accused of having links to the PKK. The predecessors of the HDP had faced trials on terrorism charges over their links to the PKK and they were all banned from politics. The BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) was founded in 2009 after the latest predecessor was closed by a judicial order, and then rebranded itself as the HDP (People’s Democratic Party) in 2012.

AK Party’s policy and the “Peace Process”

One of the most important election promises by the AK Party since 2002 has been democratisation. In 2005, then prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said Turkey should face its past in his famous Diyarbakir speech.

Erdogan’s pledge for democracy gave hope to Kurdish society in Turkey.

Erdogan said, “Denying mistakes that were made in the past is not what strong states should do. The Kurdish problem does not belong to a certain part of this society alone, but to all of it. It is also my problem.”

During an interview to a Turkish local TV channel in August 2005, Erdogan said, “The Kurdish problem and PKK terrorism or terrorism are two different things. We must not confuse the two. We must separate the two. The Kurdish citizens are my citizens. [Kurdishness] is a sub-identity. We must not confuse sub-identity with supra-identity. They must all be viewed as a whole, as citizens of the Republic of Turkey.”

The AK Party government had taken some groundbreaking steps to solve the Kurdish problem between 2005 and 2009. And in 2013, Turkish intelligence started talks with PKK’s jailed leader, Abdullah Ocalan, known as the Peace Process that ultimately aimed to disarm the group.

PKK in Syria has caused problems

During the civil war in Syria, which started in 2011, the PKK’s Syrian affiliate, the YPG, took control of some cities and villages on the Turkish border in northern Syria, enjoying the power vacuum.

Syria’s north, which has around 2 million Kurds, neighbours the Kurdish populated southeast cities of Turkey.

Turkey has also held talks with the head of the PYD, the political wing of the YPG, in order to stop their expansion in Syria and to merge with the Syrian opposition movement, which is backed by Turkey against the Assad regime in Syria.

The YPG refused to cooperate with the opposition, and instead, indirectly cooperated with Assad to control a wider territory in northern Syria.

While fighting against Daesh, the YPG gained support from Western countries, especially from the US.

The first obstacle in peace process: Kobani

Daesh attacks on the YPG in Kobani started in September 2014. Kobani is a predominantly Kurdish city in northeastern Syria and only a couple of kilometres away from the Turkish border. The fight between Daesh and the YPG sparked violent protests against the Turkish government, protesters accused Turkey of inaction.

Turkey opened its border to the civilians fleeing Kobani during the fights, and let Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga use Turkish land to reach Kobani to help the YPG in their fight against Daesh.

Despite those steps, the HDP called their supporters “to the streets to protest Daesh attacks in Kobani and AK Party’s embargo on Kobani” on October 6, with a post on Twitter. Violence broke out after protesters took to the streets, with at least 40 people killed.

Entrenchment by the PKK

During the peace process, PKK militants entrenched themselves in the cities and villages of southeast Turkey, which was seen as a preparation for another act of violence.

Turkish Armed Forces and the police started a wide-ranging operation to clear all trenches and barricades and declared the curfew in December 2015, in all the towns and cities where the fighting was going on. By that time, the peace process had already ended.

Months-long operations were supported with heavy weapons and tanks deployments. Thousands of terrorists were neutralised and cleared from city centres.

More than 350,000 civilians were displaced because the PKK turned residential areas into war zones. At least 250 civilians and 350 Turkish security forces were killed.

Both the violence over Kobani in late 2014 and the months-long clashes in late 2015 caused outrage among civilians, including the Kurds. That led to a decrease in their support for the HDP, which they accused of encouraging the PKK.

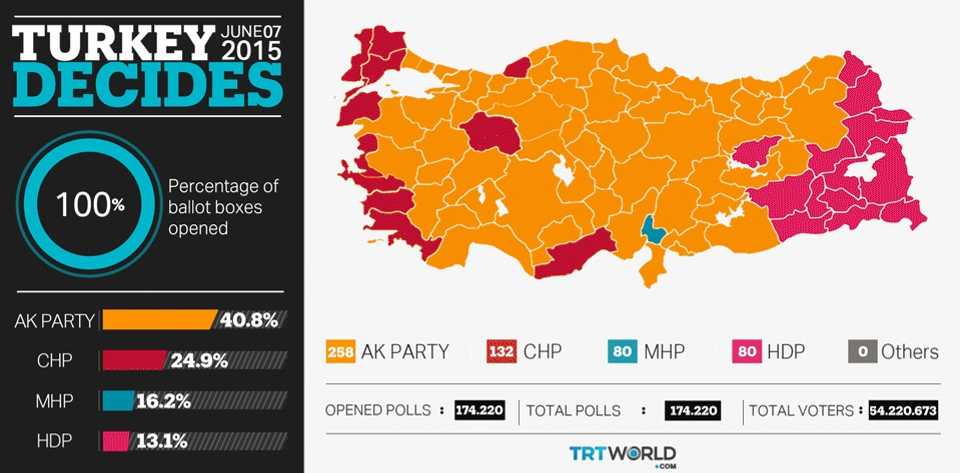

Parliamentary elections of June 2015

In the June 2015 general elections, which took place after the Kobani clashes when the peace process was still on, HDP passed the 10 percent threshold for the first time in its history and got more than 13 percent of the votes, having 80 seats in parliament. HDP was the leading party in eastern and southeastern cities, and the AK Party came in as the second party.

In Diyarbakir, one of the biggest cities in the southeast, where the majority of the population is Kurdish, the AK Party got 14 percent of the votes, while the HDP got 79 percent.

The AK Party was not able to form a government since it had less than 276 seats in the parliament, which is necessary to from a government. Political parties who had seats in the parliament failed to set up a coalition government.

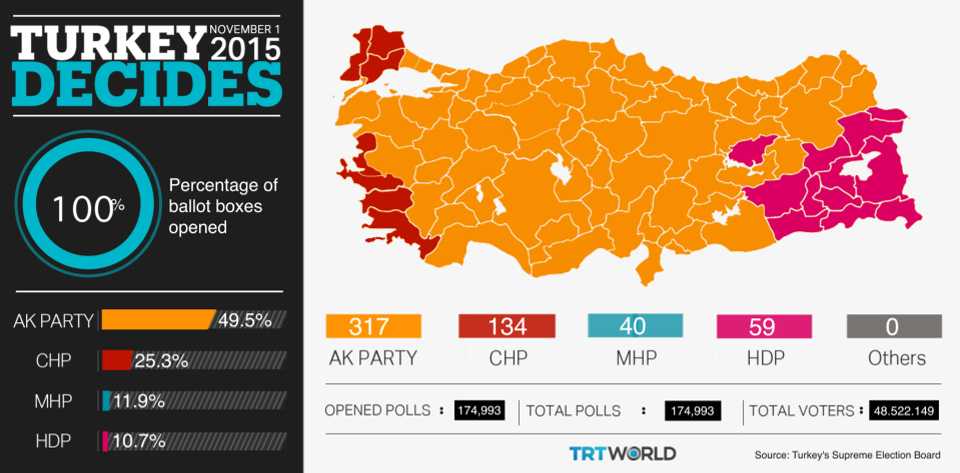

Election in five months in November 2015

Turkey went to the polls again on November 1, in the same year, since the parties couldn’t set up a new government. In the November 1 election, the AK Party received almost 50 percent of the vote with 317 deputies, while the HDP received 10 percent. In just five months, the AK Party considerably increased its votes in Kurdish-populated cities, showing that Kurds were also in need of stability instead of failed coalition governments.

The HDP got 59 seats in parliament.

The AK Party increased its votes to 21 percent in five months, while HDP’s votes decreased to 73 percent in Diyarbakir.

“The HDP was not able to form a coalition government with the AK Party despite HDP supporters expecting cooperation with the AK Party. In this respect, HDP voters were disappointed. Hence, the unwillingness of a party with 80 seats in the parliament to have an alliance with the AK Party caused serious resentment within its supporters,” Nevzat Bingol said.

According to Bingol, the Kurds who voted for the HDP were looking for more democracy. Since they couldn’t find what they had expected, they shifted to the AK Party.

Alptekin says the PKK attacks were the reason for the decrease in HPD’s votes, “From June to November, voters blamed the PKK. They thought that their votes for the HDP weren’t useful for a peaceful democratisation since the PKK could anytime highjack the ongoing talks. That’s why the HDP lost almost three percent after June election.”

PKK attacks in Turkey

Instability in domestic politics paired with a new wave of violence led to the HDP getting far fewer votes than previously.

One and a half months after the June election, the Peace Process ended when the PKK violated the ceasefire and killed two policemen when they were asleep in their apartments in late July. And the PKK attacks to the security forces continued.

But the real blow of violence came after the November elections, along with the clashes in the cities after Turkish security forces started the operations to clear all the trenches made by the PKK.

First, on February 17, 2016, a car bomb attack by the PKK killed 25 military personnel and four civilians near Turkish parliament in Ankara. One month later, the PKK targeted civilians with another car bomb that resulted in the death of 37 civilians.

On December 2016, civilians and police officers were targeted by a car bomb and a suicide attacker in front of a stadium in Istanbul’s busy Besiktas district when a football match ended and the supporters were walking out of the stadium. At least 44 people were killed and more than 100 wounded.

Referendum in 2017

Turkey held a referendum, proposed by the AK Party, for a presidential system on April 16, 2017. The AK Party and the nationalist MHP campaigned for ‘Yes’, while the main opposition CHP and HDP opposed the proposed system. ‘No’ votes were around 15 percent less than the HDP votes in the November 2015 elections in the predominantly Kurdish cities of southeast Turkey.

“I like to emphasise the importance of the votes cast in eastern and southeastern [regions]. We have seen 10-20 percent increases in all of the southeastern provinces,” Erdogan pointed out during his victory speech in Istanbul.

Decreasing turnout in years

The sign of decreasing support for the HDP is not only seen in the votes, but also in the turnout. In the June 7 election, voter turnout in eastern and southeastern cities reached a peak in modern Turkish history, with more than 85 percent.

However, from 2015 to 2017, election turnout gradually decreased. The total decrease is about 5 percent among the mainly Kurdish areas.

“Insufficiency of parties to meet electors’ expectancy and lack of confidence in politics and candidates can be seen as the reasons for decreasing electoral turnout over the years,” Nevzat Bingol told TRT World.

Alptekin gives one more reason for the lower turnout, “After the PKK moved the clashes in city centres with trenches and barricades, some people had to move out from Nusaybin, Cizre and Sur [towns in southeast Turkey]. Since they have not registered to vote in where they moved to, they couldn’t vote.”

And the second reason, according to Alptekin, is Kurdish voters’ consideration that “voting for the HDP couldn’t solve their problems since PKK was kidnapping their votes.”

What now?

According to YORSAM’s polls, “Voters still keep their silence and are still confused. In that sense, the AK Party’s interaction with the people in the region and promises for Kurdish electorate may affects votes,” Bingol explains.

Alptekin emphasizes that HDP will not be active for the second round, if there would be a second round, because they are not part of any alliances formed before the elections. So, many of them won’t go to the ballot boxes in the second round.

“Even if he can’t get more than 50 percent of the votes in the first round, Erdogan will clearly win in the second round. I think Kurds, who will go the ballot boxes, will predominantly vote for Erdogan. Erdogan’s votes from the Kurds will be higher than Kurdish votes for the AK Party in the parliamentary elections,” Alptekin said.

He added that due to their close cooperation with nationalist MHP, Erdogan and the AK Party need to convince Kurds that they will protect their rights.

Discussion about this post