May 27, 1960

Key developments

The One Party regime in Turkey came to an end with the first truly free elections of 1950. The Democrat Party (DP) won, and governed Turkey for the next decade. Large sections of the army saw themselves as the real masters of the country, and the DP as civilian rabble who had somehow usurped the traditional prerogatives of the military-bureaucratic establishment. They bided their time, and eventually jumped on the opportunity provided by economic shortages as well as continuous student unrest. A junta that called itself the Committee of National Unity arrested President Celal Bayar, Prime Minister Adnan Menderes and the rest of the DP leadership, charging them with treason. Fifteen defendants were sentenced to death, but for 12 this was commuted to various prison terms, whilst PM Menderes, Foreign Minister Fatin Rustu Zorlu and Finance Minister Hasan Polatkan were executed.

Media: At the time there was no television in Turkey, only radio stations run by the state, which were promptly seized by the junta. As there was no tradition of resisting the army, all national dailies also toed the line, mostly applauding the coup, and some of them even stooping to dirtier tricks such as circulating fake news about DP politicians so as to turn the public against them and thereby legitimize the coup.

May 22, 1963

Key developments

Some in the army did not want a return to civilian politics. The armed forces, they thought, should establish a permanent Nasser-style or Baathist-type dictatorship in order to impose what they termed “reforms.” One among such die-hards was Colonel Talat Aydemir, the commander of the Army Officer School in Ankara. Using the young cadets in his charge, he tried twice: on February 22, 1962 and May 21, 1963. The first time he was pardoned, the second time arrested, tried and executed.

Media: During his May 21, 1963 attempt, Aydemir’s cadets seized Ankara Radio, lost it, and seized it yet again, only to be silenced when the government cut all power. Aydemir admitted the importance of controlling the media, writing rather pedantically in his diary: “We were defeated because we were unable to control the radio.”

March 12, 1971

Key developments

From 1961, and especially, from the 1965 general elections onward, Suleyman Demirel’s centre-right Justice Party (with AP as its Turkish acronym) had inherited the DP’s mantle to promote economic growth and ensure a degree of democratic stability. But this was eroded by the rise of Cold War polarisation between the extreme right and the extreme left, that dovetailed into street violence. Foreign currency imbalances proved to be the Achilles’ heel of import-substituting industrialisation, inflation took off – and once more the military took advantage, intervening yet again in the name of “restoring order.” A five-man junta comprising Chief of Staff Memduh Tagmac, alongside all four force commanders issued a memorandum to force PM Demirel to resign, underwriting a series of technocratic governments. At the same time, instead of abolishing the National Assembly, they ruled through a mixture of martial law with Justice Party support in parliament.

Media: The five generals’ March 12, 1971 ultimatum was first read and announced on public broadcaster TRT’s radio broadcasts before being delivered in writing to the government. This reflected not only the importance that the top brass attached to public opinion, but also the dismissive contempt in which they held civilian government.

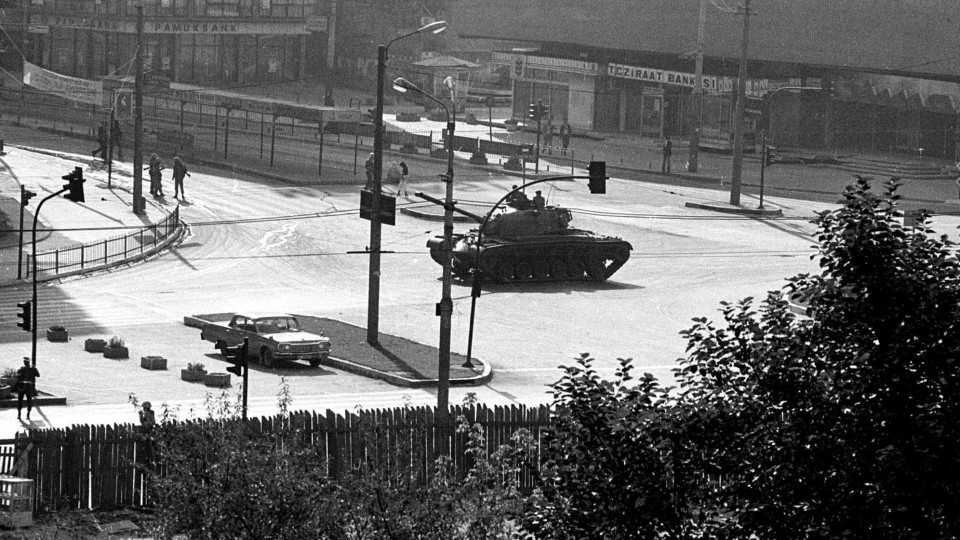

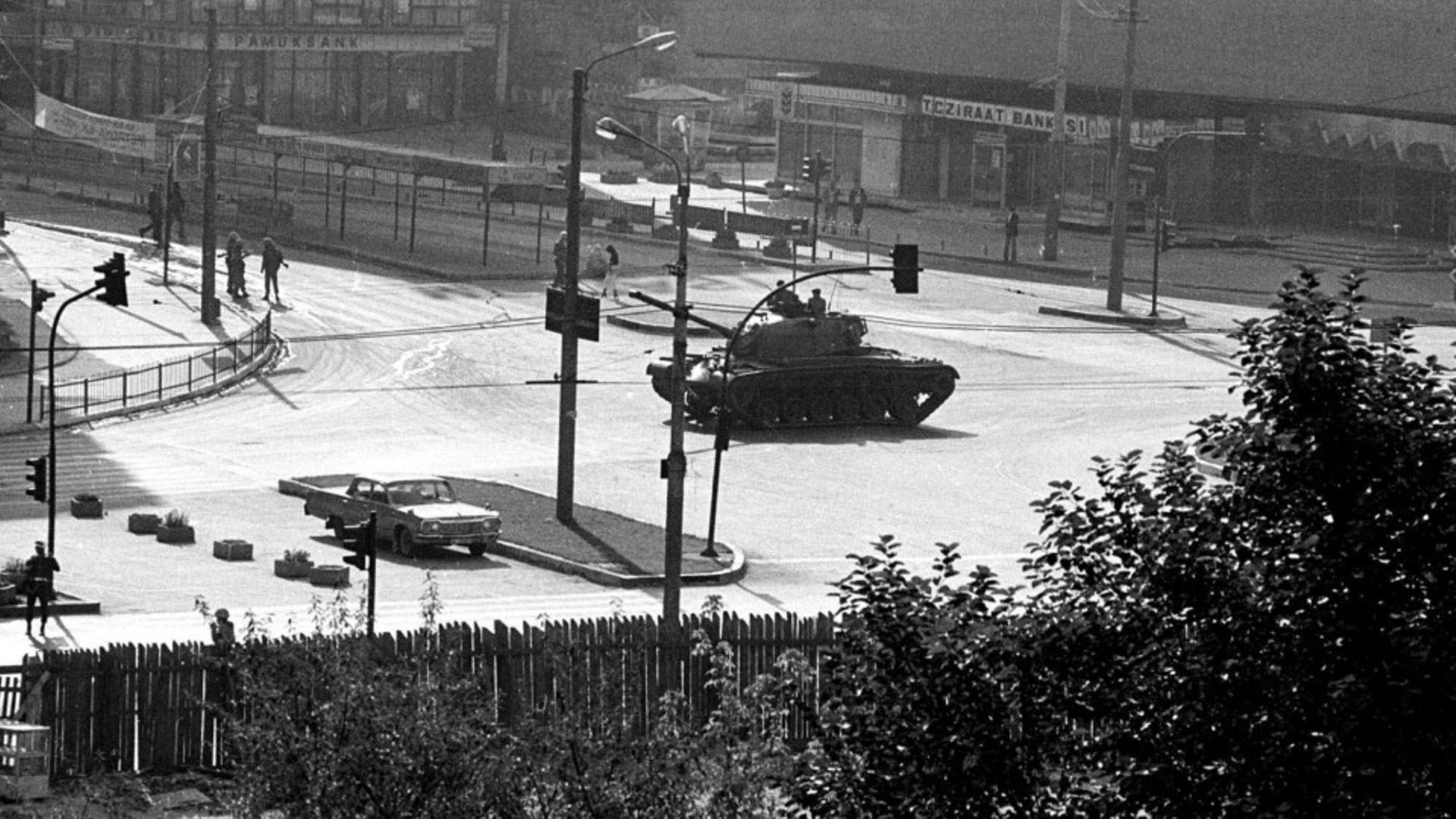

September 12, 1980

Key developments

Street violence kept escalating between the extreme right and the extreme left; the two main parties, Bülent Ecevit’s centre-left CHP and Süleyman Demirel’s centre-right AP, failed to come to any kind of centrist agreement between themselves to defend parliamentary rule, enabling the military to step in yet again on the pretext of restoring democracy. This time not only parliament but all political parties, too, were abolished, and Draconian martial law imposed, so that over the next few years some hundreds of thousands of people were arrested, many tortured, and dozens executed. Disappearances and extrajudicial killings were rampant. Chief of Staff Kenan Evren, who had led the coup, got himself elected president and remained in power until 1989.

Media: The pattern resembled the 1960 and 1980 attempts. The junta seized and controlled TRT, turning the public broadcaster into its mouthpiece. All statements and declarations were announced on radio, including martial law decrees and regulations across the country.

February 28, 1997

Key developments

Religiously led parties became more and more popular in the 90s, only to be confronted by a rigid sort of anti-democratic intransigence on the part of the military-bureaucratic establishment. Necmettin Erbakan was the long-standing leader of political Islam in Turkey, and his Welfare Party (RP in Turkish) had surprised the establishment both in the 1994 local and the 1995 national elections, emerging without an absolute majority but with a strong pluralist base. Erbakan had gone on to form a coalition with the centre-right’s Tansu Ciller (a Demirel protégée). The semi-military, semi-civilian National Security council that had become an instrument of tutelage over democratic government then issued a series of policy directives targeting PM Erbakan and the RP. Mr Erbakan was forced to resign, as was Ms Ciller. A provisional government was formed while the Welfare Party was disbanded, and several of its leaders, including current President Erdoğan, then-mayor of metropolitan İstanbul, were banned from politics for several years.

Media: The buildup to this “light” or “postmodern” coup, as it came to be called, was theatrical and even farcical at times. The media highlighted some very marginal sects, spread rumours about their allegedly sexually deviant ways, and tried to stir up secularist sentiment in general, so as to prepare the ground for a military intervention. Many such manipulations would be exposed as fake news in subsequent years.

April 27, 2007

Key developments

Parliament was due to meet and elect a new president, with the AK Party’s Abdullah Gul as by far the strongest candidate. A simple majority was needed as a quorum, and then a two-thirds majority (meaning 367 votes) would have been needed to elect a candidate on the first round. But then some high justices intervened to throw a pseudo-legal spanner in the works. Sabih Kanadoglu, former Chief Prosecutor of the High Court of Appeals (and therefore former Chief Prosecutor of the Republic) came up with the strange idea that a two-thirds majority should also be interpreted as the requirement for the National Assembly to meet in the first place. Much of the media as well as the main opposition party, CHP, started clutching at this last straw as the only means of keeping the Presidency out of the AK Party’s hands. And in a yet more obscure fashion, the Constitutional Court upheld Sabih Kanadoglu’s fiction, resulting in political deadlock. Typically, the Chief of General Staff chose precisely this moment to issue an “e-memorandum” about “secularism not just in words but in deeds,” which as a motion to get at the AK Party was generally regarded as further military intervention in political life. The deadlock was eventually broken when some political groups in parliament had enough of playing the army’s game, and appeared in the National Assembly to satisfy the two-thirds quorum requirement.

Media: The “e-memorandum” regarding the Turkish presidential election was put on the official website of the Turkish General Staff. Coverage by several mainstream media outlets was essentially pro-coup.

Click here to see TRT World Research Centre’s book reflecting on the anniversary of the July 15 coup.

Discussion about this post