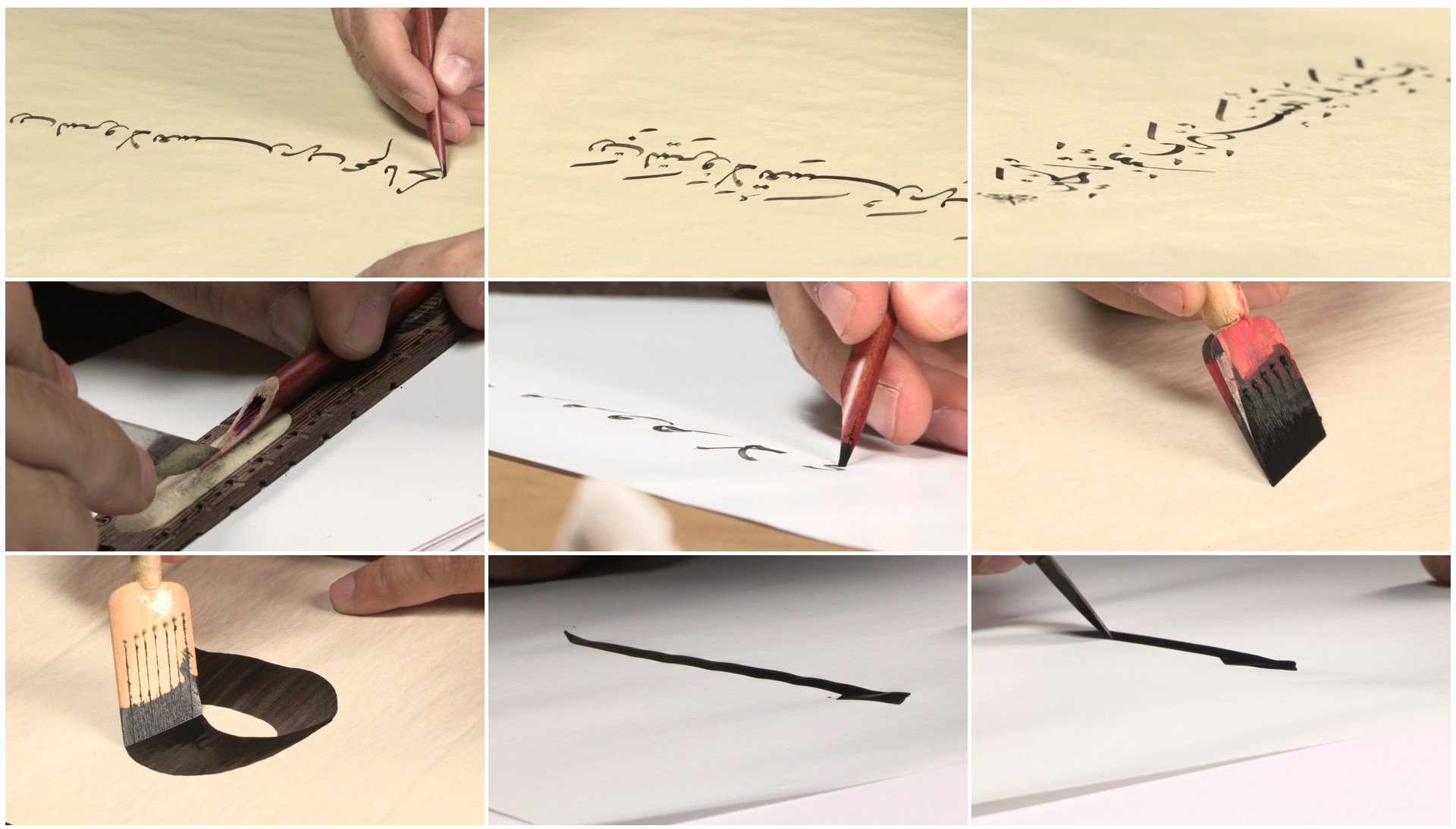

Turkish calligrapher Ömer Faruk Dere is bent low over a yellowed parchment. He traces a wisp of strokes over a cut of absorbent writing paper. In his masterful hands, Arabic script runs across the page like a visible gust, punctuated and accented with the flowing symbology of its silent echo in literate minds whose eyes have not succumbed to the usual, mundane course of language as prosaic. His calligraphic technique frees interpretation and renders meaning as sound into a historic order of visual poetry.

And under the capable lens of Ali Kazma, the angles by which to appreciate the traditional Islamic art of Dere comes into captive focus. “Calligraphy” (2013) is from the artist’s Resistance series, in which he portrays the human body as a function of grand ideas. Partway into the terse six-minute piece, Dere sharpens his writing utensil. It appears as a formidable craft on its own, complete with the disciplined precision of heightened perception required of skilled calligraphers.

The fine incisions that Dere makes across and into the elegant piece of wood that serves as his ink pen conveys a microcosmic allegory for the perfectionism of human design. It is then replaced by assortments of calligraphic writing tools. Their ends vary in width, so as to effect degrees of boldness from the medieval Semitic alphabet. With his subtle editing, Kazma shows how varying types of paper are equally influential with respect to the intuitive, creative process by which Dere embodies and conjures supernatural expression.

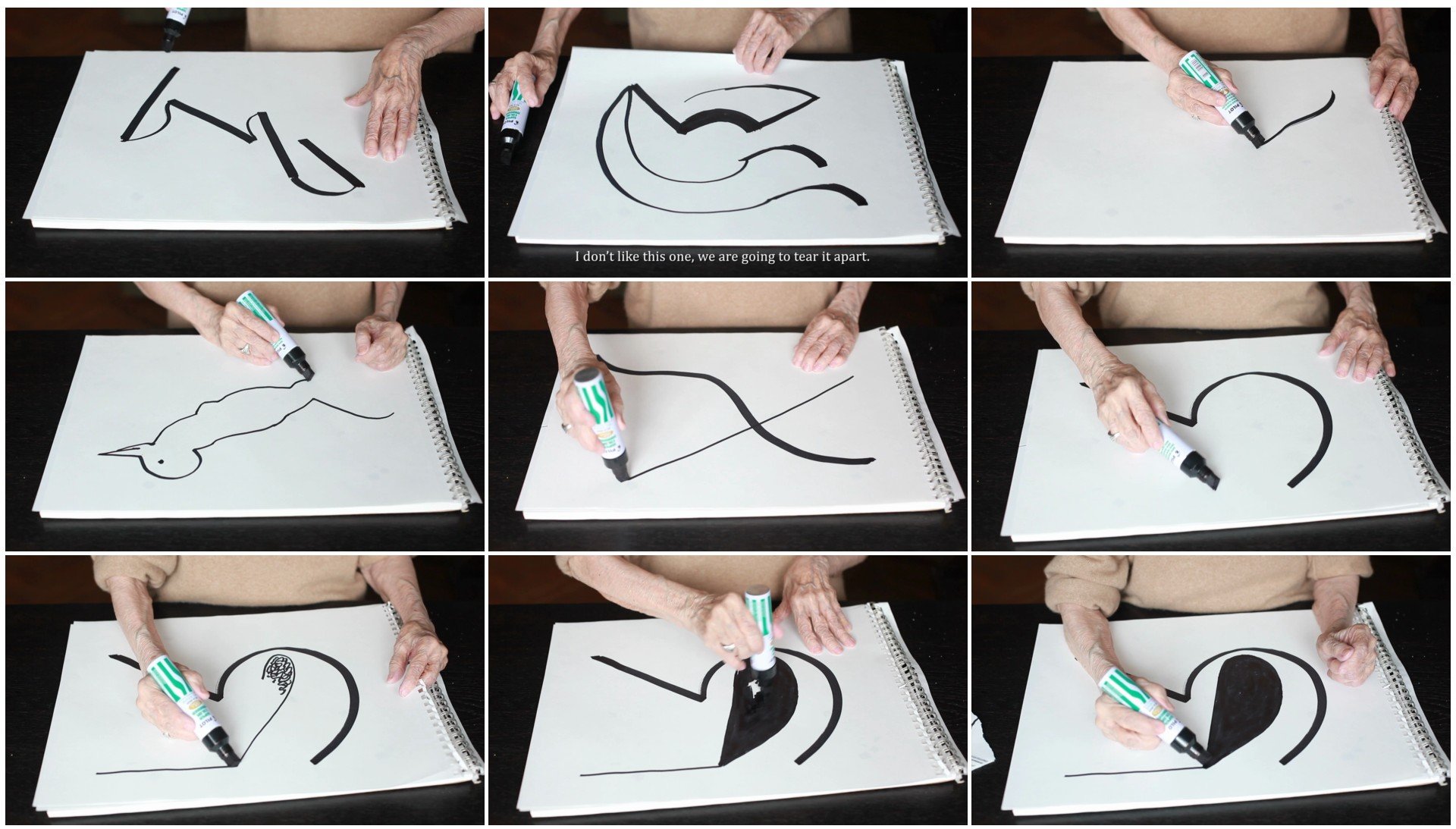

In a similar light, the late Romanian artist Geta Bratescu posed drawing as a kind of performance art in her 2014 video, “The Line.” The physicality of the act of drafting becomes more visceral than cerebral in her portrayal. A pair of elderly hands holds a thick black marker, and over a white notepad, draws a series of impromptu experiments on the nature of form. Brătescu comments, her face offscreen, frequently disliking her attempts to follow the whims of her able hands, seduced as it were by the slight rushes of her bodily momentum.

At one point in “The Line,” Brătescu draws a human figure in profile. She is not afraid to expose her most often imperfect efforts to represent natural figures. Unlike the meticulous science of calligraphy, which generally adheres to its original aesthetic, the drawings of Bratescu evokes the process-based naivety of modernism. Her style is reminiscent of that practiced by Ayşe Erkmen, particularly her series, “Elephants, Penguins, Kiwis” (2018), which was part of “Whitish,” her latest solo show at Arter’s inaugural opening.

Two is not a party

The second edition of Arter’s #playathome online video screening series features works by two artist duos. An untitled piece from 2006 by Marie Cool and Fabio Balducci questions the relationship between the person and their medium. Through the implications of their artwork, Cool and Balducci propose that there is greater reciprocity between the maker and their tools than normally perceived. Considering the idea that a tool might, from a certain angle, also use its handler, “Untitled” demonstrates the mutual visuality of the creative act.

For a brief span of 2 1/2 minutes, a woman hovers above a desk and dangles a piece of string over its sides. Her arms move parallel to its contours as she produces what could be described as three-dimensional drawings. The sketches appear as she shapes the simple white strand, forming fluid geometries that follow from her performative movements. Her body, then, mirrors the string, and not necessarily the other way around, as she looks on it with the curious, impromptu inspiration of her shared flexibility.

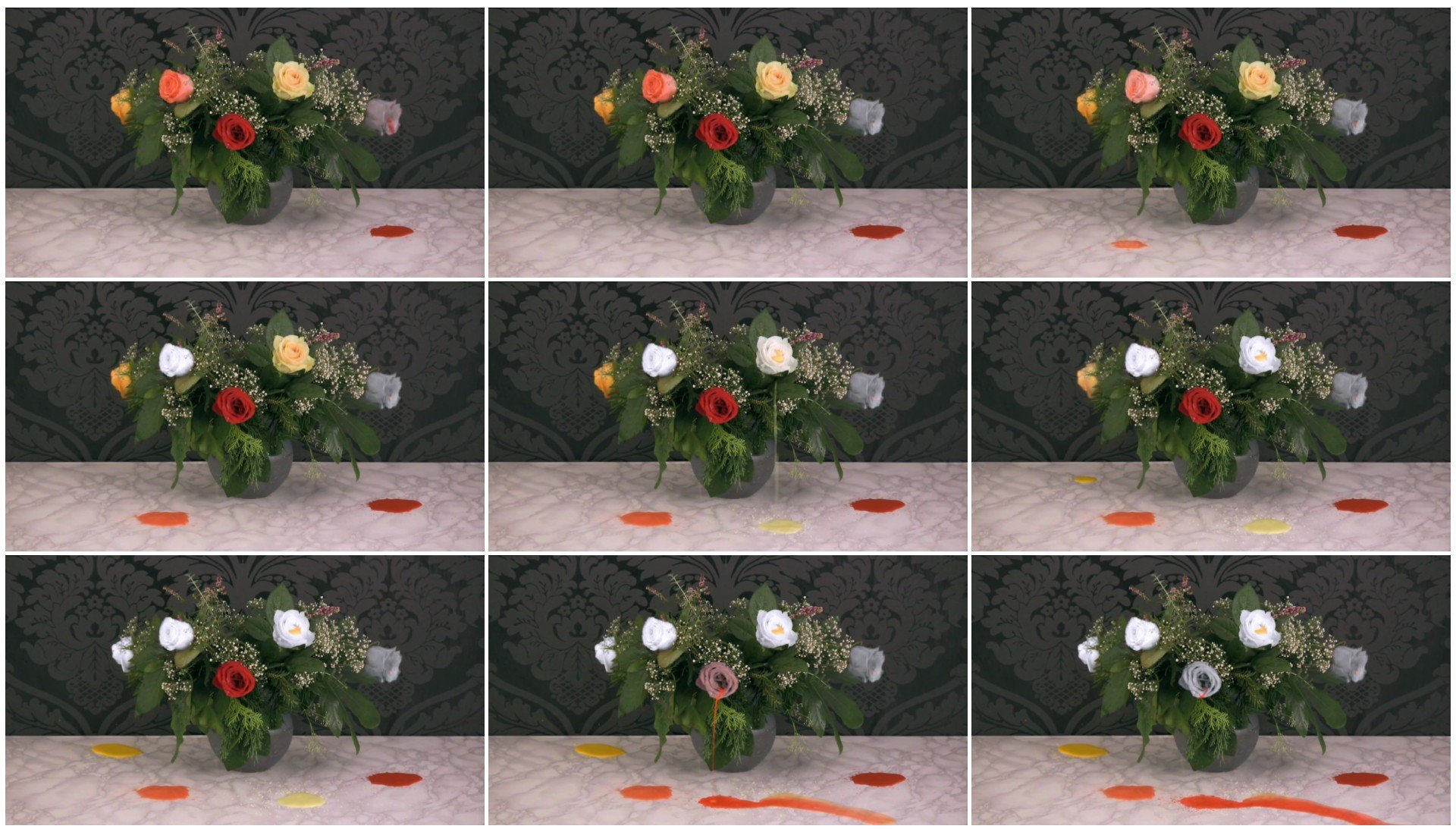

In a certain light, reflecting the dualism of their paired progenitors, “Untitled” is similar to the video by Diana Keller & Peter Rizmayer, titled “Still Life with Flowers” (2009). “Untitled” pictures a woman and a string, while “Still Life with Flowers” retraces the binary foundations of representational art with an inventive focus on the application of color. Keller and Rizmayer utilized the medium of video to produce a classical painting in reverse. Over five-plus minutes, the petals of a decorative bouquet leak out their hues and gray, in suit with the lifeless decor.

It could be said that the mother of dualities is, especially in visual terms, black and white, which shades the 33-second silent video, “Crossing Yangpu Bridge” by Josef Bares. It is a recurring theme among video artists to portray movement, not only as a material phenomenon but also as a psychological condition. Along one of the longest bridges in the world, Bares videoed a critical depiction of urbanization, juxtaposing the fast and the slow as a meditation on the transitory quality of life in the city as a function of infrastructural capacity for speed.

Another relative blip of temporal brevity is the 22-second video, “Short Program” (2013) by the young Hungarian artist Kata Tranker. In her early 20s at the time of its production, the piece is an evocation of her artistic practice, animating her drawings with a flip-book featuring the image of a figure skater, which can be read as a play on the meaning of representational art. There is a captivating twofold motion at play, as hands on-screen thumb through the sapphire blue watercolors of a skater attempting an aerial spin, falling and rising.

In through visions

At 14 seconds shy of two minutes, the video, “Constituting an Island” (2014), is imbued with ample narrative concept, yet one as invisible as its subject. The artist, Iz Öztat was born 11 years after the death of the enigmatic author named Zişan, who, as Arter confirms, appears to her in spirit and as a collaborative alter ego. Also exhibited at Arter’s ongoing group show, “What Time Is It?” there is a simple and arresting beauty to “Constituting an Island,” which centers around a succession of canoes paddling in a circular formation against a rural, mountainous backdrop.

Between the years of 1915 and 1927, history shows that Zişan composed a short story titled, “Cezire-i Cennet/Cinnet,” which translates to “Island of Paradise/Possessed.” Öztat followed in the writer’s footsteps, retracing his literary explorations to the last Ottoman territory in the Balkans, known as Ada Kaleh. But in 1968, after the construction of the Iron Gate hydroelectric plant, the island was submerged. Öztat drew attention to the loss of land and history while proving the role of art and writing in revitalization.

Last Updated on Jun 15, 2020 2:01 pm by Irem Yaşar

Discussion about this post