The new Turkish mini-series “Alef” (Aleph) is one of the productions that reached many viewers during the quarantine. Aired jointly by the Turkish streaming platform Blutv and American TV channel FX, the series centers around the murders of a serial killer with a mystical messages. In the storyline, Settar, a veteran detective at the end of his profession, starts the first murder investigation with his new partner, Detective Kemal, transferred from Scotland Yard. However, they will encounter another case before they can solve the first one. They will find themselves in the middle of a story in which Sufi codes are interspersed with a series of similar murder cases.

Starring Kenan İmirzalıoğlu as Kemal, Ahmet Mümtaz Taylan as Settar and Melisa Sözen as associate professor Yaşar Turan, the series has an original story where ambiguities unfold at a heavy tempo. The occurrence of events in Istanbul’s winter creates an even heavier atmosphere. However, our serial killer will try to tell us something by leaving messages about Sufism and cults.

Series of coincidences

In the production (spoiler alert if you don’t want to know), the killer asks the team to find and print a novel within a week. The novel written by Faik Ahlat Karaca, who committed suicide in the 1960s, should be published by one of the best-selling publishers. Otherwise, new murders will follow.

Their research on this novel takes the team to associate professor Turan from Istanbul University’s Department of Islamic Research, because her article is the only one they can find on the topic. With her involvement, the story shifts toward Ottoman history, mysticism and religious groups.

The clues left by the killer in the murders lead us into a mystical setting. For example, he draws the symbol of Aleph, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet which signifies the number one and indicates the oneness and unity of the creator, with blood on the wall. This symbol can also be seen in the way the murderer ties up his victims. He inserts an antique dervish mirror into the belly of one of the bodies. Most importantly, the novel, which he wishes to be published, tells about the arson of a marginal religious group.

At the home of one of the victims, a miniature painting draws the attention of detective Kemal. This painting is also present in the novel that the killer wants to be published. The traces of the miniature lead them to a still active Sufi community. While the team looks for the owner of the miniature, who is also a friend of author Karaca, they reach the name of a businessman who has lost his mind. Coincidentally, this man is none other than Turan’s father.

Consulted only for Karaca at first, Turan once again crosses paths with Kemal. Based on both the content of the novel and other clues in the murders, Kemal wants to learn the details of the link between the religious groups and these murders. Turan will tell Kemal about the marginal religious communities, especially the Qalandariyya-Malamatiyya mystical groups.

Two different theses on history

There are problematic points in Turan’s information about Qalandars and other religious groups. The script seems to have been built in line with the theses built by the socialist historians in Turkey.

According to the thesis, marginal religious communities like the Qalandariyya were eliminated because they did not submit to the official ideology of the Ottoman Empire. This thesis again suggests that these dervishes represent the religious understanding of the commons and the lower classes. Upper classes, especially the Sunni ulema, cannot tolerate this situation. The Ottoman central administration imposed its own ideology by suppressing these communities. Our killer in Alef believes in the same ideology. Is this the actual truth?

Ahmet T. Karamustafa from Washington University Department of History and Religious Studies refutes this thesis. His book titled “Gods Unruly Friends: Dervish Groups in the Islamic Later Middle Period” is one of the most comprehensive works of these marginal dervish communities.

He states that these groups in the Islamic world do not reflect “popular Islam” but are minority dervish communities with marginal ideas and practices. He also draws attention to the inaccuracy of categorizing such dervish groups according to classical classes and interpreting them in a modern framework such as “hostility to ideology.”

Inquisition in Ottoman Empire?

One of the most remarkable and realistic scenes in the series is the dervish arson scene where the details of the mentioned novel were animated as if they were real. Here we seem to be watching a witch hunt scene of the Medieval Inquisition. However, such a situation occurs in neither Western nor Eastern sources.

State intervention against a certain group, whether religious or not, has two conditions in Ottoman history. This group should either display behaviors that would disrupt public order or should provoke the people with hatred and a grudge to encourage rebellion and attempts of revolution. This is still true today.

Although they are non-Sunni and non-Islamic, many groups that pay attention to these values have survived. However, the Kadizadelis, who seem excessively Sunni, were liquidated even if they side with the state’s ideology. The state treated the communities according to their effects on the social order and economy, rather than their ideologies. The same is true for the Qalandariyya, Haydariyye, Malamatiyya, Bektashiyya, and many other religious communities.

Who are Qalandars?

Like Detective Kemal, we are curious about these dervish movements. In Sufism, Qalandariyya is the first community that comes to mind regarding the religious orders of Malamatiyya.

The Arabic word “malamah” means “scolding, condemnation, blame, shame.” In Sufism, it refers to “a religious group, which does not give importance to settled rituals such as clothing, dhikr and rite and which is based on self-blame, self-condemnation, and thus moving away from the compliment of the people and getting closer to God.”

In addition to the same meanings as the malamah, the word “Qalandar” in Persian means “one who doesn’t care about worldly goods, tolerant, mild-tempered, humble.” Qalandariyya is a movement that does not attach importance to the appearance of worship, try to win hearts with sweet words, pay much attention to following fards or religious duties in Islam commanded by God, at prayers and is not fond of the worldly goods.

It is stated that it deteriorated by marginalizing over time in different regions. In the sources, they are called “antinomians (those who see everything permissible) and the zindiqs (those who look religious and do not perform the basic requirements of religion), and we also see positive or neutral names such as Qalandariyya and Abdalan-ı Rum. This controversial situation is related to the disinformation of Qalandariyya at different times and regions.

The deterioration is based on two important reasons. The first is the deterioration of the political and demographic structure from Asia to Anatolia as a result of the Mongol invasions, and the religious groups to be dispersed and exposed to abuse. The second is that in the Iran-Ottoman conflict, Iran made its propaganda through some religious groups and installed intelligence functions on these groups. Therefore, those who have been identified with Iran have been severely liquidated. It is understood that the ability of Qalandariyya to show itself down and outward is misused in various ways.

As a result, there are two types of Qalandars. While the first group is those who are actually Sunni, perform their worship but try to seem miserable and deranged and thus break their desire to show hypocrisy and arrogance, the second group is those who do the begging, fortunetelling and reject the basic orders and prohibitions of Islam and do so with the dervish guise and arguments.

Qalandars through the eyes of travelers

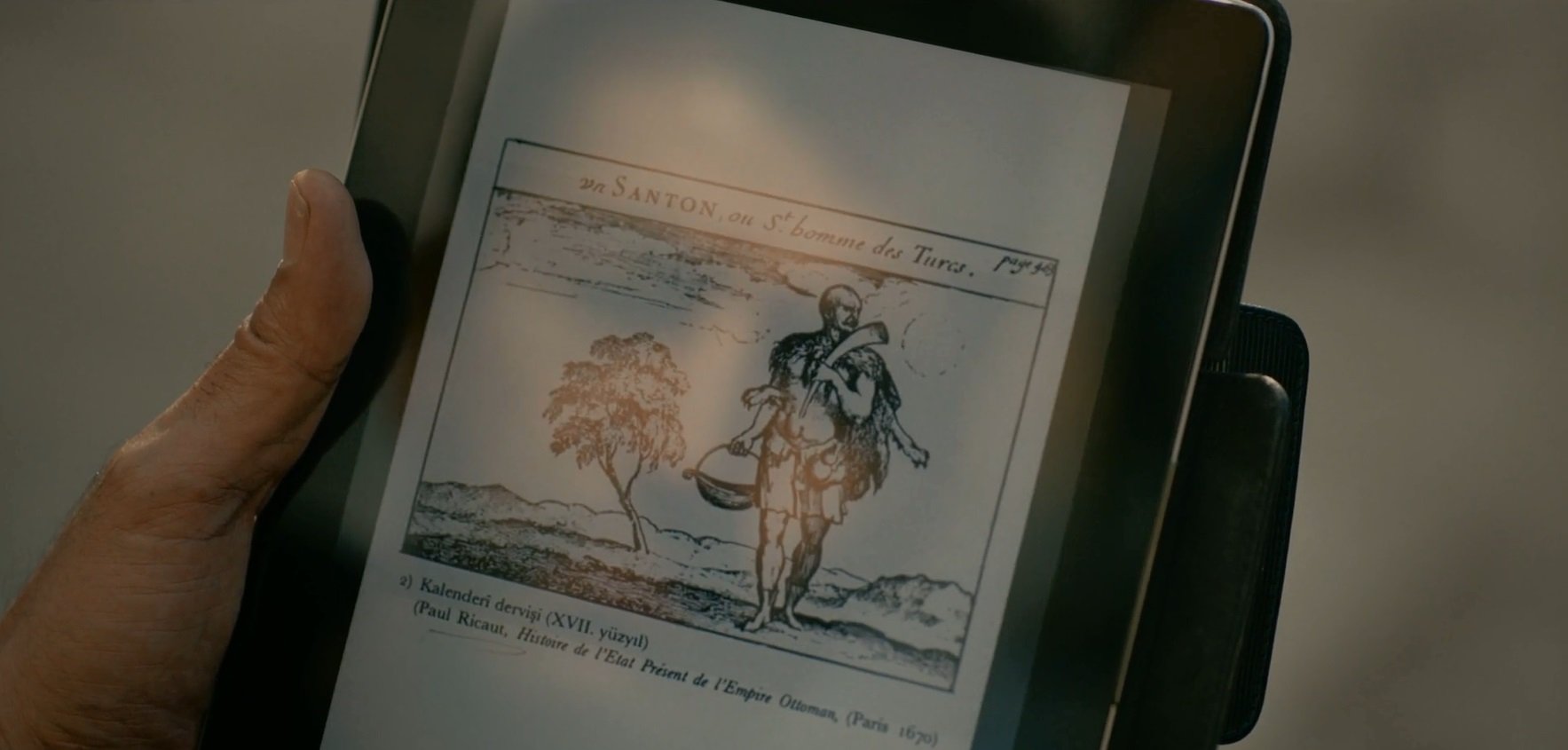

Turan tells Kemal that the travelers are talking about these Qalandari dervishes and show the pictures they drew. For example, Spanish traveler Ruy Gonzales De Clavijo says that he passed through the village called Delilarkent (the city of Deliler, today called Deli Baba) in Erzurum, in Eastern Anatolia, where strange dervishes resided.

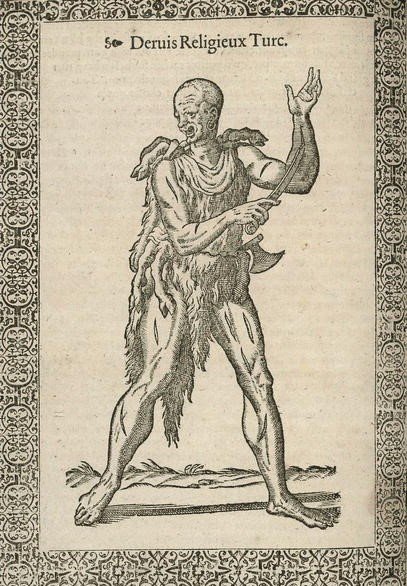

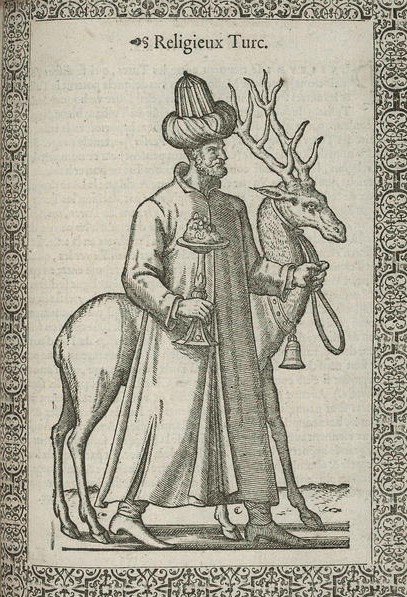

Other travelers traveling the east in various centuries talk about dervishes in similar ways. Some travelers like Nicolas De Nicolay also drew pictures of the dervishes called “abdal, Torlak, Qalandar.”

The most detailed observations about the appearance of marginal dervish groups are made by Giovan Antonio Menavino. In his book, he describes the groups we call the second type as follows:

“Dressed in sheepskins, the torlaks (read Qalandars) are otherwise naked, with no headgear. Their scalps are always clean-shaven and well rubbed with oil as a precaution against the cold. They burn their temples with an old rag so that their faces will not be damaged by sweat. Illiterate and unable to do anything manly, they live like beasts, surviving on alms only. For this reason, they are to be found around taverns and public kitchens in cities. If, while roaming the countryside, they come across a well-dressed person, they try to make him one of their own, stripping him naked. Like Gypsies in Europe, they practice chiromancy, especially for women who then provide them with bread, eggs, cheese and other foods in return for their services. Amongst them, there is usually an old man whom they revere and worship like God. When they enter a town, they gather around the best house of the town and listen in great humility to the words of this old man, who, after a spell of ecstasy, foretells the descent of a great evil upon the town. His disciples then implore him to fend off the disaster through his good services. The old man accepts the plea of his followers, though not without an initial show of reluctance, and prays to God, asking him to spare the town the imminent danger awaiting it. This time-honored trick earns them considerable sums of alms from ignorant and credulous people. The torlaks … chew hashish and sleep on the ground; they also openly practice sodomy like savage beasts.”

In short, “Alef” seems to arouse curiosity about other religious groups and Sufism besides the references to the Qalandarriye. It also shows the groups that continue their activities underground. How the series will continue is now an enigma. Will it present a successful fiction story, or will it make the audience bored with its heavy pace? We will see all this in the following episodes.

Last Updated on May 13, 2020 2:33 pm by Sinan Öztürk

Discussion about this post