Last Tuesday, April 21, marked the 47th death anniversary of one of the most prolific authors and intellectuals in Turkish literature – Kemal Tahir.

Known for being a realist and a social justice warrior, Tahir put his goal in writing in this single phrase: “To tell the drama of a man who finds himself in trouble within a context of events.”

He wrote about real people, and himself. He portrayed the lives of those living in rural Anatolia and gave insights into their feelings – the conflicts and confusion they experienced after moving to chaotic cities, dealing with an uncomfortable culture shock. His works also carried a didactic tone, chastising the twisted relationship between hungry landlords and sharecroppers in villages.

Let’s see how his life shaped his whole career and many works.

Tahir was born in Istanbul in 1910 to parents who had both been in the service of Sultan Abdülhamid II and his royal family. His father, Captain Tahir Bey, was an aide to the sultan, while his mother Nuriye Hanım, was a maid to Naile Sultan, Abdülhamit’s daughter. And although it seemed like he was lucky being born into a courtly family, life was not kind to him from the get-go.

His mother died when he was a teenager, and he had to discontinue his studies at the Galatasaray High School and start working.

Between the years 1928 and 1932, he worked as a lawyer’s assistant and also served as a warehouse officer in a coal mine in the northern Turkish province of Zonguldak.

Then in 1932, Tahir embarked on his journalism career, which would eventually shape his future. He was mentored by some of the most famous and leading authors of the period, namely Yakup Sabri, Ertuğrul Şevket, İsmail Safa and Arif Nihat Asya during this time. He even dabbled in art publishing, leading print efforts for the art magazine Geçit (Passage or Gateway in English), which was discontinued after just seven issues.

That same year, he also started working as a proofreader, interviewer and translator at the Vakit, Haber and Son Posta newspapers. This stint lasted until 1938.

He also took on more administerial duties as secretary at the Yedigün (Seven Day) and Çizgi (Line) magazines, all the while producing work as lead writer at the daily Karagöz and becoming editor-in-chief for the daily Tan (Dawn).

In 1938, when Tahir joined the military, he was tried on charges of “inciting military rebellion” along with Nazım Hikmet, another famous Turkish poet and novelist.

After spending 12 years behind bars for political reasons, Tahir was released based on the general amnesty scheme in 1950.

He wrote several novels while he was doing his time: Zoraki Nişanlı, Bir Nedim Divanının Esrarı, Cami Kıran Çocuk, Halk Plajı, Gönül Denilen Hayvan and Aşk Pınarı.

Aware of the political situation and driven by a sense of responsibility and social justice, he refrained from using his real name, İsmail Kemalettin Demir, in his works until 1954. He adopted the pen name, publishing his works as Kemal Tahir until that year.

Following his release from prison, Tahir set off toward Istanbul and started working as the Istanbul correspondent of the İzmir Commerce newspaper.

After working in various newspapers and publishing houses, he founded the Düşün (Think) Publishing House along with Aziz Nesin in 1957.

However, when the 60s came round, the author shifted his entire focus in his novels.

The celebrated novelist focused on topics such as the Ottoman period, the constitutional monarchy and Republican period, the one-party regime, village institutes, and Asian-style production.

His novel Devlet Ana (Mother State, 1967), which defines the ideal state by attributing to Turkish history, made a great impact both in literature and on the political agenda in 1967. The novel contains many historical and cultural references, drawing from the famed tales of Dede Korkut and several Anatolian legends as well as verses from the Holy Quran and the Bible.

He received the 1967-1968 Yunus Nadi Novel Award, one of the most prestigious cultural and arts awards of the period in Turkey, for his novel “Yorgun Savaşçı” (“The Tired Warrior,” 1965), which tells the story of a Turkish soldier who fought for the independence and liberation of Turkey.

In 1968, he also received the Turkish Language Association’s Novel Award for his novel Devlet Ana.

His untimely death came at the age of 63 on April 21, 1973, due to a heart attack.

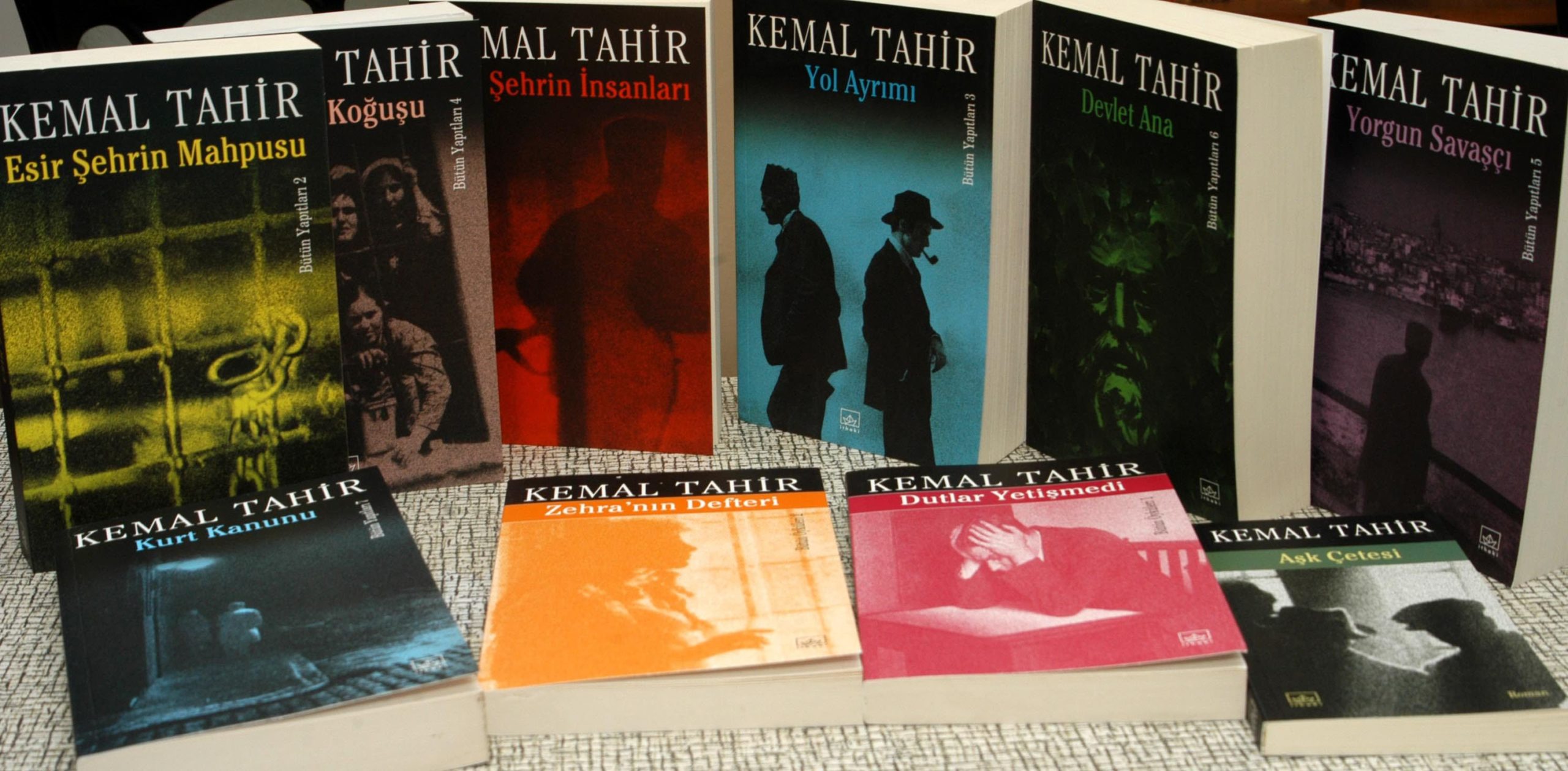

His written works:

Stories: “Göç İnsanları” (“The People of the Lake,” 1955)

Novels: “Sağırdere” (1955), “Esir Şehrin İnsanları” (“The People of the Captive City,” 1956), “Körduman” (1957), “Rahmet Yolları Kesti” (“Mercy Waylaid,” 1957), “Yedi Çınar Yaylası” (“The Highland of the Seven Plane Trees,” 1958), “Köyün Kamburu” (“The Village Hunchback,” 1959), “Esir Şehrin Mahpusu” (“The Prisoner of the Captive City,” 1961), “Bozkırdaki Çekirdek” (“The Seed in the Steppe,” 1962), “Kelleci Memet” (“Memet, the Headhunter,” 1962), “Kurt Kanunu” (“The Law of the Wolf,” 1969), “Büyük Mal” (“The Big Merchandise,” 1970), “Yol Ayrımı” (1971)

Posthumous novels: “Namusçular” (“The Defenders of Honor,” 1974), “Karılar Koğuşu” (“Women’s Ward,” 1974), “Hür Şehrin İnsanları” (“The People of the Free City,” 1976), “Damağası” (“The Lord of the Roof,” 1977), and “Bir Mülkiyet Kalesi” (“A Fortress of Possession,” 1977).

Some of his works have also been adapted to cinema, namely “Yarın Bizimdir” (“Tomorrow is Ours,” 1963), “Haremde Dört Kadın” (“Four Women in the Harem,” 1965) and “Namusum İçin” (“For My Honor,” 1966).

Last Updated on Apr 24, 2020 5:18 pm

Discussion about this post