Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, the world-famous modernist poet, novelist and literary critic, wrote that three authors determined the fate of the modernization of Turkish literature in the Tanzimat era of the 19th century, two of which are well known. Namık Kemal, the leader of the Edebiyat-ı Cedide (New Literature) movement, is known by everyone interested in the Turkish poetry and writing of that time, and Ziya Paşa, Kemal’s best friend, who is also familiar to those who have to say something about 19th-century thought and literature.

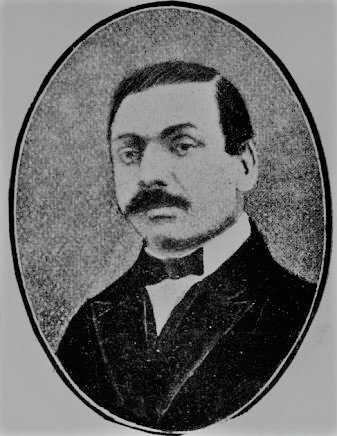

Ibrahim Şinasi, however, is the No. 1 pioneer of the so-called new literature and is the “secret box” mentioned by Cahit Tanyol, late sociologist and literary critic. Interestingly, Turkish language and writing departments have paid little or no attention to Şinasi’s life and work, perhaps because of the prejudice that he was not a major poet or that his writing was only valuable for its attempts at modernizing Ottoman thought and literature.

On the other hand, the only considerable thesis on Şinasi came from a sociologist, Bedri Mermutlu. He wrote a book on Şinasi as part of the history of modern Turkish social thought. According to Mermutlu, Şinasi was the first Turkish thinker to have a social agenda, which made him “the original example of the complete intellectual in Turkey.”

Early life

Şinasi was born in 1827 in the Tophane quarter of Istanbul. His father Mehmet was an artillery officer who died in the Russo-Turkish War (1828-1829) when Şinasi was only a toddler. Şinasi’s mother, Esma, who was originally from Istanbul, raised him alone. Şinasi was born, lived and died in the same house in Tophane, which is Firuzağa today.

Şinasi attended a district school before he was admitted to the Tophane Kalemi (Artillery Division Office), where he worked on both his reading and writing. His masters included Ibrahim Efendi and Mehmet Reşat Bey, a French convert who taught him Arabic and French. He also learned Persian from a Sufi leader, Sheikh Zaik Efendi, together with Hersekli Arif Hikmet, a talented bureaucrat and thinker of the Tanzimat era.

Şinasi worked for 10 years at the Tophane Kalemi, a time when he experienced an introduction to Tanzimat Westernization. Bey helped him get permission from Sultan Abdülmecid to visit Paris and enroll at a local college there. Şinasi was sent to Paris in 1849 to improve his French and knowledge about Western civilization. This was one of the first samples of a pattern that saw the Ottomans, and the Turkish Republic in later years, send young public servants and students to Europe so that they could bring back knowledge to improve the Turkish state based on a Western model.

Birth of a Westernist

The young poet improved his language skills and entered into Orientalist circles in France. He was a member of Societe Asiatique, a French learned society dedicated to the study of Asia. Şinasi was the second Ottoman national in the group. He met several significant figures, including French writer Alphonse de Lamartine and philosopher Ernest Renan, through the association. The French paid great attention to Şinasi thanks to his vast knowledge about Eastern cultures and languages. Societe Asiatique’s biannual academic journal covering Asian issues, “Journal Asiatique” referred to Şinasi as “the high-level official of the Ottoman government,” which was of course not completely true.

Şinasi returned to Istanbul in 1855 with excellent French and understanding of French literature. He then wrote a special book on Turkish language traditions called “Darub-i Emsal-i Osmani” (“Samples from Ottoman Idioms”), which included about 2,500 Ottoman idioms.

Officially, Şinasi worked at the French government office for finances, to acquire experience in accounting, but he refused to continue after his return. He instead became a member of the Education Council, which signaled his intentional move toward cultural and educational affairs.

Bearded or not

Şinasi wrote a eulogy for the former Grand Vizier Reşit Pasha in 1856, for which Ali Pasha, the incumbent Grand Vizier, fired the author. The Sadaret (Grand Vizier’s office) mentioned: “Şinasi Efendi is to be dismissed from his post at the council and excluded from the payroll as he must be disciplined for his actions and shave his beard, which does not suit neither his rank nor function.”

A short time later, Ali Pasha’s government collapsed and Reşit Pasha replaced him. The new government gave Şinasi his previous position at the Educational Council back and included him on the payroll again by the end of the same year. He later wrote another eulogy for Reşit Pasha and gave a petition suggesting that he was obliged to shave his beard for sanitary reasons.

Şinasi translated French poetry and published it in a special volume in 1859. He also founded and published the first Turkish newspaper Tasvir-i Efkar (Imagery of Thoughts) together with Agah Efendi in 1860. Tasvir-i Efkar should be considered Şinasi’s masterpiece from which he enacted his social programs and published books. His publications helped to create a public sphere for the Ottoman intellectuals.

Significant issues were discussed in the newspaper including reason, science, civilization and law. He was speaking as a reformer, who refused local traditions, either religious, literary or public. Şinasi was the first Ottoman intellectual who wanted a complete Westernization of Turkey so that it could become a full member of the modern world.

He indirectly criticized the new Sultan Abdülaziz in some of Tasvir-i Efkar’s editorials, which cost him his position as a public servant. Abdülaziz ordered his dismissal, and Şinasi was fired from his government position for the second time. Mustafa Fazıl Pasha supported Şinasi and his newspaper for the rest of Şinasi’s life. In a few years, Şinasi became involved in a conspiracy against Abdülaziz and visited Paris often, meeting Turkish, Italian and French politicians.

On the other hand, he was not a natural-born politician. In his second visit to Paris, he worked on an “Ottoman Lexicon” and he refused to get involved with the Young Ottomans, who also traveled to the city. Though Namık Kemal would praise Şinasi as “the leader of the New Ottomans” in later years, he never actually showed up in history.

Şinasi returned to Istanbul in 1867 at the request of Sultan Abdülaziz via Fuat Pasha. He was not happy, however, and he stayed in Istanbul for only a couple of months and returned to Paris for the third time after divorcing his wife, who had asked Fuat Pasha to help to acquire Şinasi’s home in Istanbul.

After two years, Şinasi eventually returned to Istanbul, where he died on Sept. 13, 1871.

Last Updated on Jul 10, 2020 3:14 pm by Irem Yaşar

Discussion about this post