Though Turkish architectural patrimony dates back to prehistoric ages and includes the works of various civilizations, modern Turkish architecture started with the deliberate policy of the state to cut ties with the Ottoman tradition, the latest link of the patrimonial chain. The republican administrators left too many monumental works of Turkey to ruin until the 1930s when the initial preservation endeavors began.

However, the Turkish architectural tradition is still considered as a matter of heritage and preservation, and not as a possibility of resilience and continuity. Very few attempts have been made to renew or reinterpret the domestic architectural values, forms and construction styles. Besides, when the Turkish-Islamic tradition is considered, the general inclination is to think about public architecture, whether liturgical or official. Turkish traditional housing, which indeed has continued until recently, was not credited much in the range of architectural debates until the early 1970s.

Reinterpreting artistic tradition

The 1970s experienced a shift toward the domestic traditions in the fields of arts and thought. While Turgut Uyar, a major ultra-modernist poet belonging to the Second New movement, published a poetry volume named “Divan,” a modernist interpretation of the Ottoman diwan poetry, many young poets took a left-wing populist path toward the folklore. Filmmakers also began to make populist movies with rural themes, while photographers took humanistic pictures of Anatolia. Rediscovery of Anatolia promised the resilience of the Turkish people with their eclectic lifestyle and artisanship. Turkish handmade arts, artifacts that constitute 75% of all cultural industry exports from Turkey today, were discovered and public policy began to preserve those. Marketing also helped to carry the Turkish artisanship to the future.

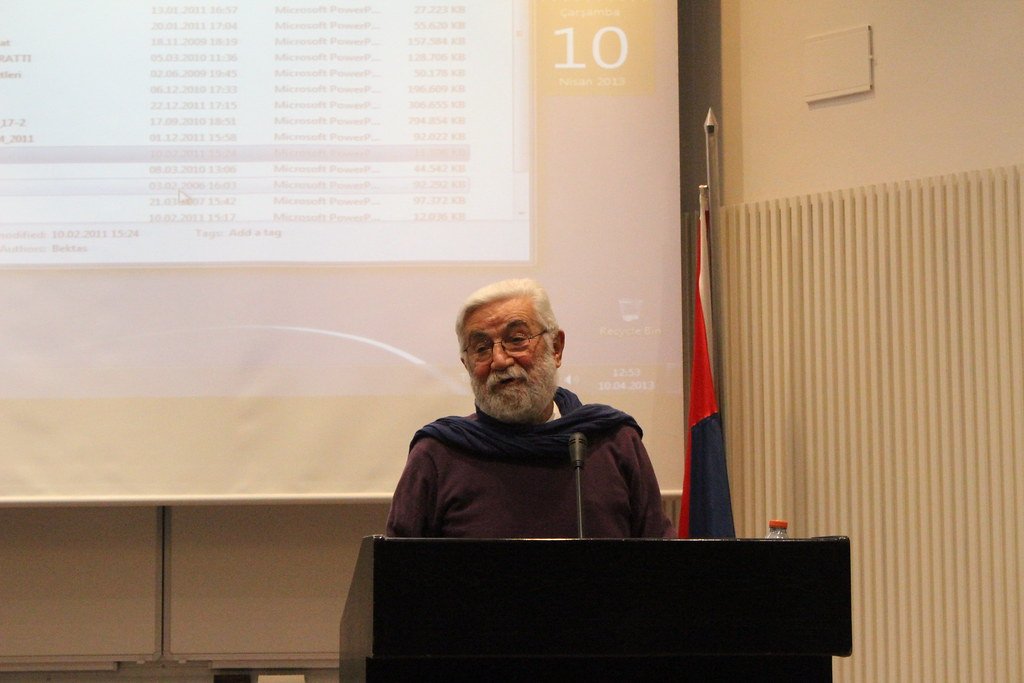

On the other hand, Turkish people’s housing architecture that has never employed architects, designs or plans could resist until a certain point. The population increase, geometrically increasing economic needs and modern housing projects became a great pressure on the humble but resilient housing tradition. Too many old but beautiful houses have been destroyed to make way for apartment buildings. Besides, only a few architects considered reinterpreting the Turkish vernacular housing traditions. Cengiz Bektaş, a poet and an architect, is the best-known person to make such attempts. Bektaş has repeatedly said that he understands the tradition as something that has the resilience and continuance, not as a dead heritage, which explains his reinterpretations of Turkish housing in his individual housing projects.

Architect

Bektaş was born on Dec. 26, 1934, in western Denizli province in a crowded family including eight siblings. He was schooled in Istanbul. He graduated from the Istanbul Erkek Lisesi (Boys’ High School) in 1953. An interesting thing about Bektaş’s early life is that he refused the money coming from his father, mother and uncle. Instead, he asked his father to sponsor him until he finished high school on a condition that he passed the classes with honor. He thought that he should earn on his own, and he really did. He was good at painting; so, he decided to study architecture at a university.

Bektaş graduated from the State Fine Arts Academy Architecture Department in 1956 and Munich Technical University Architecture Department in 1959. He founded a cooperative at school in order to help his underprivileged friends in buying expensive books at cheaper prices.

Though Bektaş was invited by the Middle Eastern Technical University (METU) as a lecturer, he refused this offer thinking that his English was not sufficient to give courses at METU. Instead, he chose to have a career as a private architect. He started his own business with a friend, Oral Vural. Bektaş and Vural departed in 1969, when they had won 25 prizes already. Bektaş decided to work alone and not to apply for any prizes after that.

Bektaş gave lectures at the Mimar Sinan University City Planning and Architecture Department (1961-1962 and 1999-2000), Zafer Engineering and Architecture College at Ankara (1967-1969) and Trakya University Architecture Department (1998-1999). He also gave graduate courses on architecture and living culture at the Istanbul University Sociology Department. Bektaş offered lectures as a visiting professor in such countries like Macedonia, Germany and the U.S.

Bektaş had a special interest in the Anatolian vernacular architecture. He examined, wrote and lectured on the traditional Turkish housing since the early 1970s. His published works covering designs, photographs and narratives about the traditional houses in various districts of Turkey including Bodrum, Antalya, Şirinköy (Gökçeada), Akşehir, Kuşadası and other places. “Türk Evi” (Turkish House) book is his masterpiece.

Poet and essayist

Though Bektaş is a famous architect and lecturer of architecture, he also has a good reputation as a poet and essayist. Belonging to the “Blue Anatolia” movement — a humanist artistic and philosophic movement in Turkish — Bektaş has written on people and land, offering a perspective on Mediterranean civility. Bektaş was also the chairman of the Turkish-Greek Friendship Association and Pen Turkey for years.

Bektaş received many awards as an architect, poet and essayist, including the Agha Khan Award, Turkish National Architectural Award, Turkish Language Institute (TDK) Poetry Award and others.

Last Updated on Mar 05, 2020 5:58 pm

Discussion about this post