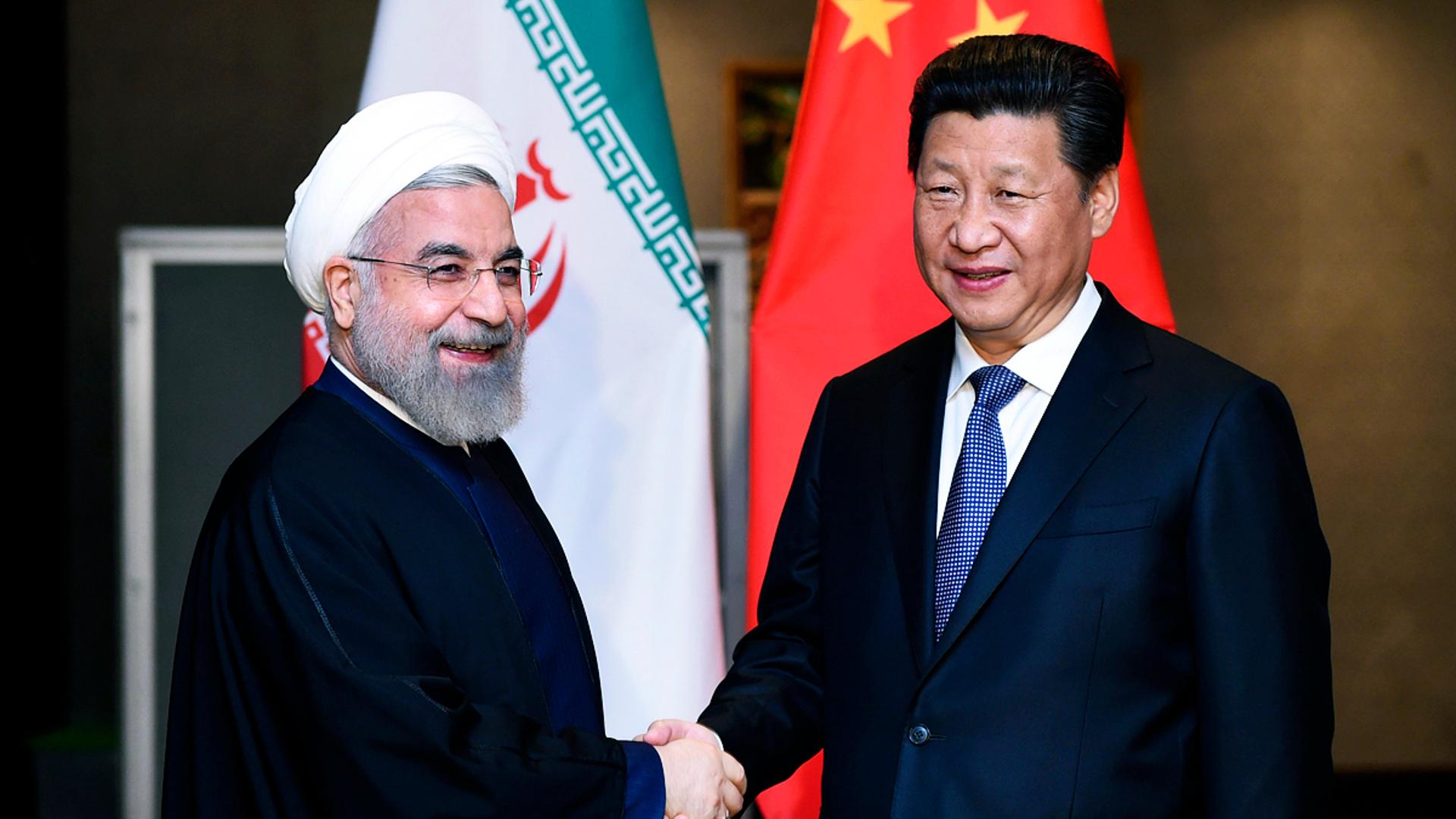

Iran and China are deepening their strategic relationship. For Turkey, this could mean a more regionally emboldened Iran.

During a parliamentary session in July, Iran’s Foreign Minister, Javad Zarif, acknowledged for the first time that his country is negotiating a 25-year strategic partnership with China. The announcement came after a storm of criticism about the secretive plans.

Many experts, conservative lawmakers, and even former officials, such as Iran’s former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, voiced their opposition and accused the government of hiding the details surrounding the agreement.

Some of them went even further and suggested the pact will allow China to plunder the country’s resources with the blessing of the regime, relinquish the country’s sovereignty, and turn Iran into a client-state for China.

Shortly after, an 18-page draft text was leaked on social media. Some experts claimed that it is the general framework that both sides are negotiating. The document reflects a desire to promote the strategic partnership between Iran and China not only in areas that cover the economy, energy, finance, trade, tourism, infrastructure, and communication sectors, but also other domains such as security, defence, military, and intelligence.

Unlike in other countries such as India, Pakistan, and some Arab Gulf states, the Iran-China pact was not the focus of attention in the Turkish press, mainly because Ankara has more urgent regional issues to worry about.

That said, it would be a mistake to ignore the implications of such a deal on Turkish strategic calculations in the region – especially on a security level. If sealed, the agreement could pose challenges to Turkey’s vital interests and upset the balance with Iran.

Turkey and Iran are regional rivals with contrasting agendas, visions, and interests. Syria is the most visible example of the rivalry between the two countries; Ankara chose to support the Syrian people while Tehran opted to back Bashar al Assad’s regime.

In Iraq, Tehran blocks further economic and security cooperation between Turkey and Iraq and prevents Ankara’s economic and security interests from surpassing northern Iraq.

When it comes to the Gulf, although the Saudi-led blockade against Qatar in 2017 forced Doha and Ankara to draw closer to Iran, Tehran is not happy with the Turkish military presence in the Gulf.

In Libya, there has been increasing evidence of Iran’s support towards its allies (Assad and Russia) who support the warlord Khalifa Haftar against the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) backed by Turkey.

In this context, there are three things concerning the Iran-China pact that might sound an alarm in Ankara. First is the question over how Iran is going to use the money it will receive from Beijing.

The strategic agreement will allow Tehran to circumvent US sanctions allowing it access to a large basket of funds in return for the oil it sends to China. Will Tehran choose to use the money to fund its malicious regional activities and proxies, or help its own people? This will complicate Ankara’s mission in places like Syria, Iraq, and possibly Libya, too.

Second, given the proposed cooperation between Iran and China in the defence industry – there is speculation that a UN arms embargo on Iran may expire in October – things could become much more challenging for Turkey.

Iran already supplies its proxies, IRGC franchises, and allies with a variety of weapons including anti-tank weapons, anti-ship weapons, anti-air weapons, drones, Katyusha rocket launchers, and even ballistic missiles. Hezbollah, for instance, has Iranian made ballistic missiles that can reach as far as Iraq, Jordan, and the Sinai in Egypt.

The proliferation of Iranian-made weapons with the help of China would constitute a bigger security risk for Ankara. During the last few years, Tehran has aided Ankara’s foes in Syria, Iraq, and Libya with weapons.

Since 2016, Turkey has noticed an increase in Iranian-made weapons possessed by the PKK, an organisation recognised as terrorist by Turkey, the US and the EU.

In Syria, the situation was no different.

During the Olive Branch Operation in Afrin in January 2018, Turkey seized a huge cache of Iranian-made weapons that belong to the YPG, the Syrian branch of the PKK terror organisation. Recently, Iran pledged to equip the Assad regime with anti-air defence systems.

Another worrisome issue for Turkey would be Iranian-Chinese military cooperation. Some have suggested that Tehran and Beijing are negotiating the possibility of a mega arms deal that would boost Iran’s conventional military capabilities in an unprecedented way, particularly since the establishment of the Islamic Republic.

This development, coupled with several other factors, such as advancing its long-range ballistic missile capabilities, could heighten Ankara’s threat perception.

The lack of advanced conventional capabilities in Iran and the NATO defensive umbrella, have always boosted Ankara’s confidence, all the while diluting any sense of a security threat emanating from Iran.

Yet, the Syrian crisis and the Turkey-Russia standoff at the end of 2015 showed that the NATO umbrella has flaws and might not protect Turkey when push comes to shove.

When it comes to China, the pact with Iran is expected to boost its presence and influence in the Gulf, and the region, in an era of US decline. This variable could harm Ankara’s regional interests and challenge its rising security role.

Turkey and China are at odds on several regional issues. Although Beijing tends to portray its involvement in the region as purely neutral and of an economic nature, the last few years have uncovered otherwise.

China, for example, backed the Assad regime against its people by using its veto at the UN security council 10 times between 2011 and 2020. This is 66.6 percent of the Chinese vetoes used since the People’s Republic of China became a permanent UN Security Council member on 25 October 1971.

These vetoes in favour of the Syrian regime, have resulted in emboldening Assad, increasing the death toll of civilians, protecting him against punishment for using chemical weapons, exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in Syria, the burden of refugees, and the security risks towards Turkey.

China has actively blocked aid from reaching Syrian refugees and internally displaced people through neighbouring borders. The most recent case of vetoing cross-border aid came last month where Beijing used it twice.

Moreover, Chinese weapons have been increasingly used by several countries and militia groups against Turkey, its interests, and allies.

On the Libyan front, Haftar relied heavily on advanced Chinese weapons, such as Wing Loong-2 drone versus the Turkish backed UN-recognised GNA. An Iran-China pact that would empower Beijing in the region, would only fortify this trend and increase the regional threats coming from China.

Finally, the 2017 Gulf crisis has prompted Turkey to play a direct role in the security of the Gulf for the first time in almost a century.

The Iran-China pact might offer a military foothold for Beijing in the area. Although the Iranian government is denying this, many reports suggest that the strategic Kish Island will be handed over to China and turned into a military base, while others anticipate that Beijing could be offered military facilities elsewhere along the Iranian coast.

While Ankara and Beijing have no capacity, nor the will to substitute the US security role in the Gulf, giving China a foothold in that region will certainly complicate Turkey’s calculations.

Author: Ali Bakeer

Dr. Ali Bakeer is an Ankara-based political analyst/researcher. He holds a PhD in political science and international relations.

Source

Discussion about this post