Growing scepticism of vaccines in Europe, especially in countries like France should be a cause for concern.

Vaccinations are essential; the World Health Organization nor I can stress that enough. This past week in Toulouse, France, for example, a case of measles was reported on one of the city’s largest campuses. This is just one of the 90,000 cases in the first half of this year alone in Europe. To put that into perspective, in all of 2018 a little over 84,000 cases were reported.

The increasing prevalence of this preventable disease in this region shows an emerging trend of a mostly Western mistrust of immunisation.

This past September, a global summit hosted by the European Council took place in Brussels, and the central focus was vaccinations (or the lack thereof) and the current risks at play. What can be highlighted is that there is a growing mistrust of vaccination, fear of side effects, and, “herd immunity.”

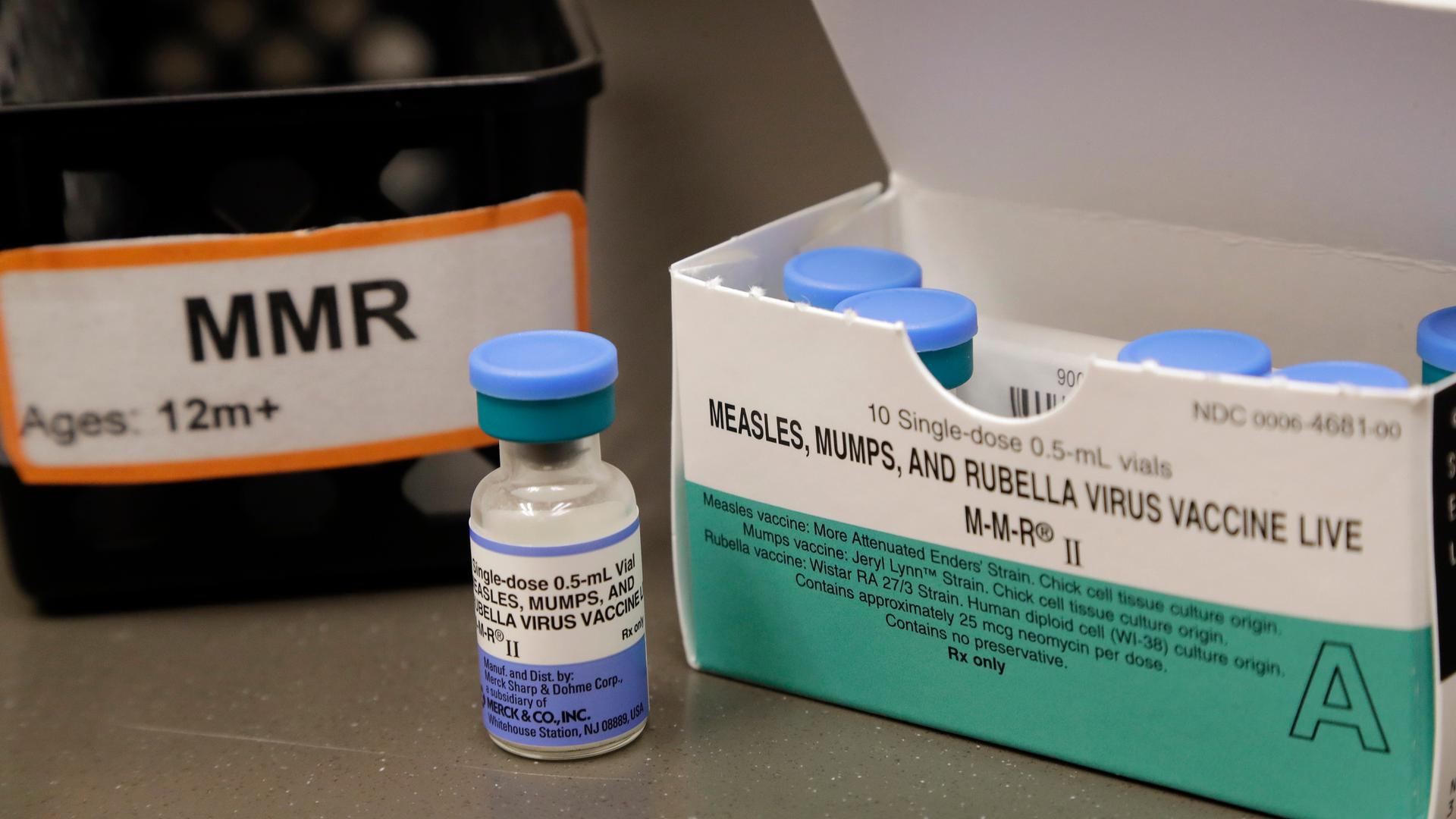

Several references cite the general spread of disinformation to be the leading cause in the mistrust of vaccines and overall declining trust in science. Fear of side effects has also been affected by misinformation – particularly the false information that the MMR vaccine that protects the individual from Measles, Mumps, and Rubella causes autism.

This leads back to an almost fictional study released in the late 90s in the UK that has been disproved time and again. The paper’s author, Andrew Wakefield, had his medical license revoked – he had falsified results. However, this was another trigger to a still ongoing battle of false information around the subject.

Important to understand the pressing need for all people, particularly children, to vaccination is the concept of herd immunity. This means that when a sufficient number of the population is vaccinated against the disease, an outbreak can be prevented. But declining numbers opting to vaccinate on the European continent according to recent trends is causing an increase in preventable disease.

Figures from the Brussels meeting show that 50 percent of the population in the EU believes vaccination causes severe and damaging side effects, and 38 percent believe that vaccinations cause the disease they claim to be protecting against.

In France, a substantial amount of the population, 30 percent, believe vaccines are not safe – making the French the least likely internationally to trust in immunisation. The World Health Organization has marked these beliefs and general hesitancy towards vaccines as one of the main threats to global health in 2019. In France, a large part of the distrust is due to the misunderstood actions of the resale of H1N1 vaccines in 2010 – where unsubstantiated claims led to a dip in public confidence.

Strangely, there is no fixed vaccination policy across the EU, and each country implements some mandatory and other optional choices. These differing policies end up decreasing the public’s awareness and imply that it is not a top priority and that there are diverging governmental positions on vaccinations – though the opposite seems true.

The three main recommendations are currently in the process of being adopted: an EU common vaccination card, investment into vaccination research, and the conception of a vaccine information sharing system.

In contrast, a large number of developing nations already have mandatory vaccination policies in place combined with a generally high faith in the importance of immunisation.

A study found in 2018, countries with the highest conviction in the effectiveness of vaccination came mainly from so-called developing nations. The highest reported was India and Bangladesh, joined by countries such as Egypt, Iraq, Rwanda, Ethiopia, and Liberia.

The United Arab Emirates, joined by several other countries, employs a mandatory vaccination policy and is implemented by schools and their medical staff to ensure that all children in the country are vaccinated in a timely and effective manner. Even recent breakthroughs such as the HPV vaccine have already been incorporated into this system.

The high levels of trust held in these nations are likely due to the public witnessing their effectiveness first-hand. There are several case studies in the MENA region, in central Africa and some parts of Asia where outbreaks were either prevented or quickly controlled by immediate immunisation efforts.

The cholera outbreak in Iraq in 2015 and the Middle East polio outbreak earlier in 2013 were ultimately controlled through mass immunisation by a coalition including the American Center for Disease Control. Unfortunately, it is these same countries that have the most difficulty in accessing vaccines.

In India, public health has been a social and political priority since 2010. The country has made great strides eradicating a number of preventable diseases including polio and tetanus. The country has undertaken a second immunisation wave beginning in 2017 that aims to protect 405 million children from measles and rubella by the end of this year.

Differing local and international perceptions may give the impression that it is not vital to your nor the public’s health. However, vaccinations have eradicated diseases, controlled outbreaks, and saved millions of lives since their introduction to public health.

Avoiding vaccination is a massive public health risk with potential mass impact. It is the responsibility of every individual to find information on the matter and to understand how to filter facts from fiction.

Author: Nadine Sayegh

Nadine Sayegh is a multidisciplinary writer and researcher covering the Arab world. She has covered topics including gender in the region, countering violent extremism, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, amongst other social and political issues.

Source

Discussion about this post