The reported deal between the two countries has been overstated, and its motives misunderstood.

The relationship between China and Iran has been in the spotlight recently. A huge, 25-year deal is reportedly being considered that would see $400 billion of Chinese investment in Iranian energy and transport infrastructure in return for oil supplies discounted by as much as 32 percent, along with ramped up security cooperation that might involve Chinese troop deployments and the transfer of Persian Gulf islands to Beijing’s control.

Prominent US media outlets such as the New York Times and Washington Post see the deal as proof that Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran has failed. Far from isolating Tehran, as intended, the policy has driven it into the arms of Beijing.

In Iran, politicians have attacked President Rouhani’s government for selling out to China, with ex-president Ahmadinejad slamming the “secret” deal in a June speech.

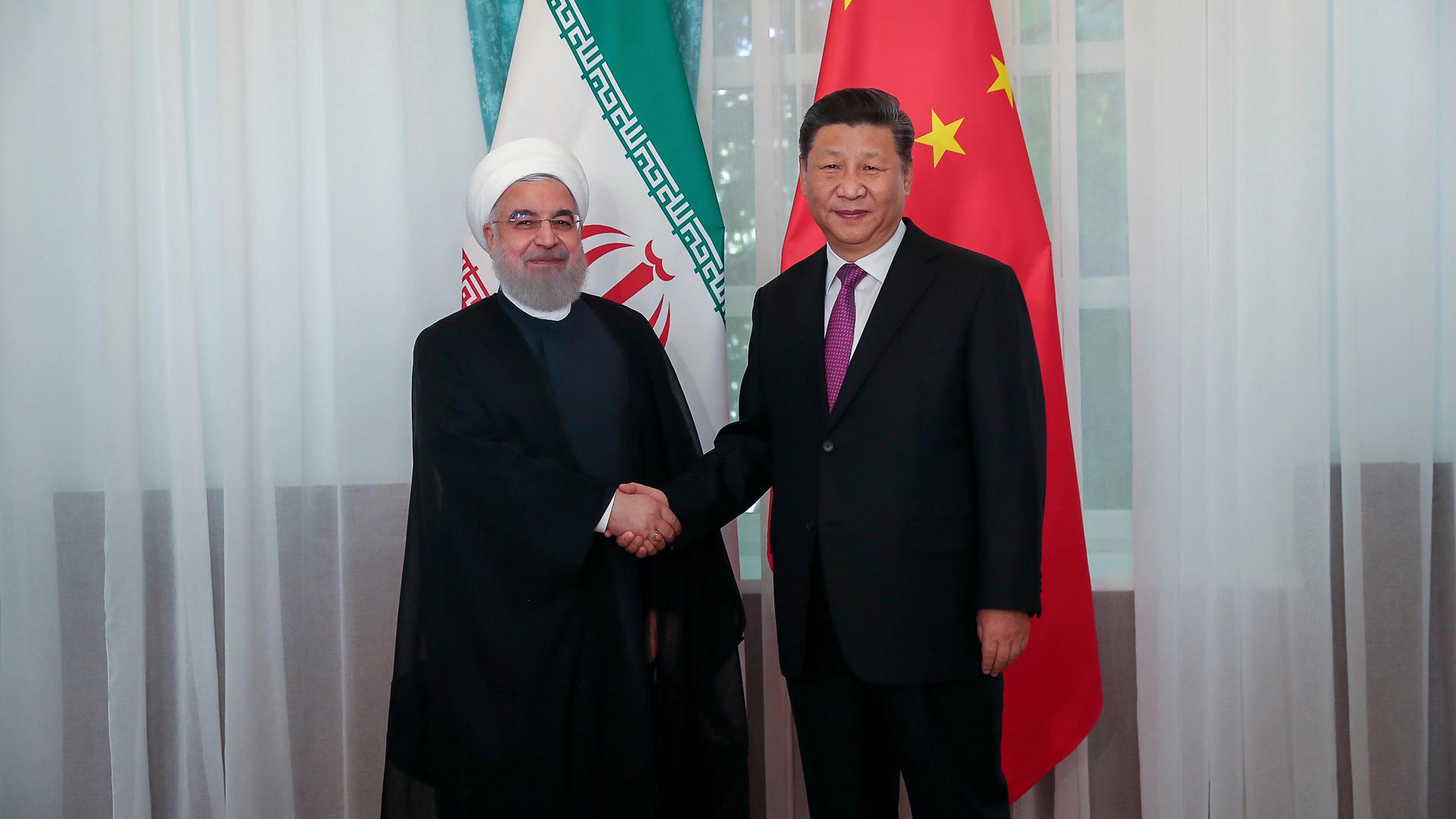

But this is all hype. The deal is not a secret pact concocted recently in response to Trump’s aggression, but the long-expected fleshing out of a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’ (CSP) publicly agreed between presidents Xi and Rouhani in 2016.

The text of the 2016 partnership states that “both sides agree to put consultations and discussions aimed at concluding a bilateral 25-year Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement on their agendas”.

A version of the plan has been leaked online, although the Iranian government has not yet confirmed its authenticity. The document is far less impressive than some reports suggest. It makes no mentionof the $400 billion statistic, of discounted oil, or of troop deployments and Iranian islands. It is little more than a roadmap, laying down broad areas of potential cooperation without granular detail.

And it is not unique. China has CSPs with other Middle East countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE (both Iranian rivals). Far from engaging in the sort of bloc politics that characterised the Cold War, when there were American and Soviet spheres of influence, Beijing aims to cooperate with all states in the region, including US partners. To assume that China wants an anti-American alliance with Iran is to misconstrue its strategic approach.

The numbers don’t add up

Reports of a $400 billion Chinese investment package are wildly implausible. According to the American Enterprise Institute, China invested $26.92 billion in Iran from 2005 to 2019. To go from that level of investment to a triple digit figure while the Iranian economy is reeling from US sanctions and low oil prices is, to say the least, far-fetched, especially when one considers that Chinese investment in Iran has been on a downward trajectory for years.

In 2016, after the nuclear deal (JCPOA) had been concluded and sanctions lifted, China invested $3.72 billion in Iran. By 2018, that figure had fallen to $2.08 billion and, by 2019, to $1.54 billion.

Now compare that with the UAE, where China invested $4.15 billion in 2016, $8.01 billion in 2018, and $3.72 billion in 2019, even though the Emirates is a much smaller country. Likewise with Saudi Arabia, which received $5.36 billion investment in 2019.

No doubt a large cooperation agreement between China and Iran, of the kind that is being reported, would raise eyebrows in GCC countries, some of which fear Iranian aggression.

Does Beijing really want to jeopardise its important economic relationships with Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and others for the sake of an impoverished pariah state which is on a crash course with the US?

Chinese companies have often struggled in Iran. Some projects have faced delays, such as work on the North Azadegan oil field, which got going six years after the contract was signed in 2009. Others have stopped. China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) was booted out of the South Azadegan oil field in 2014, for example, and last year it withdrew from the South Pars gas field, having done so before in 2012.

According to data tweeted by Iran expert Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, China earns more from projects in Saudi Arabia and Iraq than in China, “where turnover hasn’t grown since 2009,” while hosting significantly fewer Chinese labourers. Last year there were more than 200,000 Chinese expatriates in the UAE, far more than in Iran.

Iran and China have a history of exaggerating their economic prospects. In 2016, they agreed to boost bilateral trade to $600 billion, an unrealistic goal even before US sanctions were reimposed. Previously, in 2011, they had aimed to increase trade to $100 billion, which eventually had to be revised down to $60 billion.

Although China is Iran’s top trading partner and an important economic lifeline, commerce has been greatly attenuated by US sanctions. Despite fears that China would ignore the restrictions and continue to trade with Iran, its oil imports have fallen off a cliff, dropping by a massive 89 percent between 2019 and 2020.

This is partly because China wanted to appease the US and secure a ‘phase one’ trade deal. Analysts often point out that the US is far more important to China than Iran. When Trump imposed new sanctions on the Iranian economy in early 2020, China was quick to comply. The trade deal was signed soon after.

A pawn

Tehran has become something of a pawn in Beijing’s fraught relationship with Washington. Chinese experts interviewed for a recent Chatham House report spoke dismissively of Iran, saying it was peripheral to China’s national interest, while noting that Chinese businessmen “do not believe that it is worth doing business with Iran, given the difficulties involved.”

Progress on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Iran has certainly been minimal. Rail freight between China and Europe tends to pass through Russia, not Iran. And, in any case, most goods travel by sea, which is cheaper. The BRI has fared much better in the Gulf, where the China-backed port at Khalifa in Abu Dhabi is already up and running.

But reports that China and Iran might increase their military cooperation are realistic and in line with recent naval exercises. However, troop deployments are improbable, as they would anger the Gulf states and might be unpopular in Iran. In 2018 controversy erupted when Russian aircraft used an Iranian base for refuelling.

It is feared that China will greatly increase its arms sales to Iran once a UN arms embargo expires in October. But Iran might not be able to afford Chinese weapons, and has developed an indigenous production capability for drones and other equipment. Furthermore, US sanctions prohibit Iranian arms imports, even without the embargo.

For all the gushing rhetoric coming out of Beijing and Tehran, China is not popular with Iranians. This became apparent during the coronavirus crisis, when Iran’s health ministry spokesman slammed China on Twitter for presenting misleading information about the virus, prompting the government to quickly row back his comments.

Although the Sino-Iranian relationship is often exaggerated, Iran has vast resources and great economic potential that could be unleashed if sanctions were removed. Should Joe Biden win the 2020 US presidential election, the JCPOA might be restored, which would improve China’s prospects.

Either way, Beijing will keep the door to Tehran open, even if little can be expected from their relationship in the short term. China usually takes the long view.

Author: Rupert Stone

Rupert Stone is an Istanbul-based freelance journalist working on South Asia and the Middle East.

Source

Discussion about this post