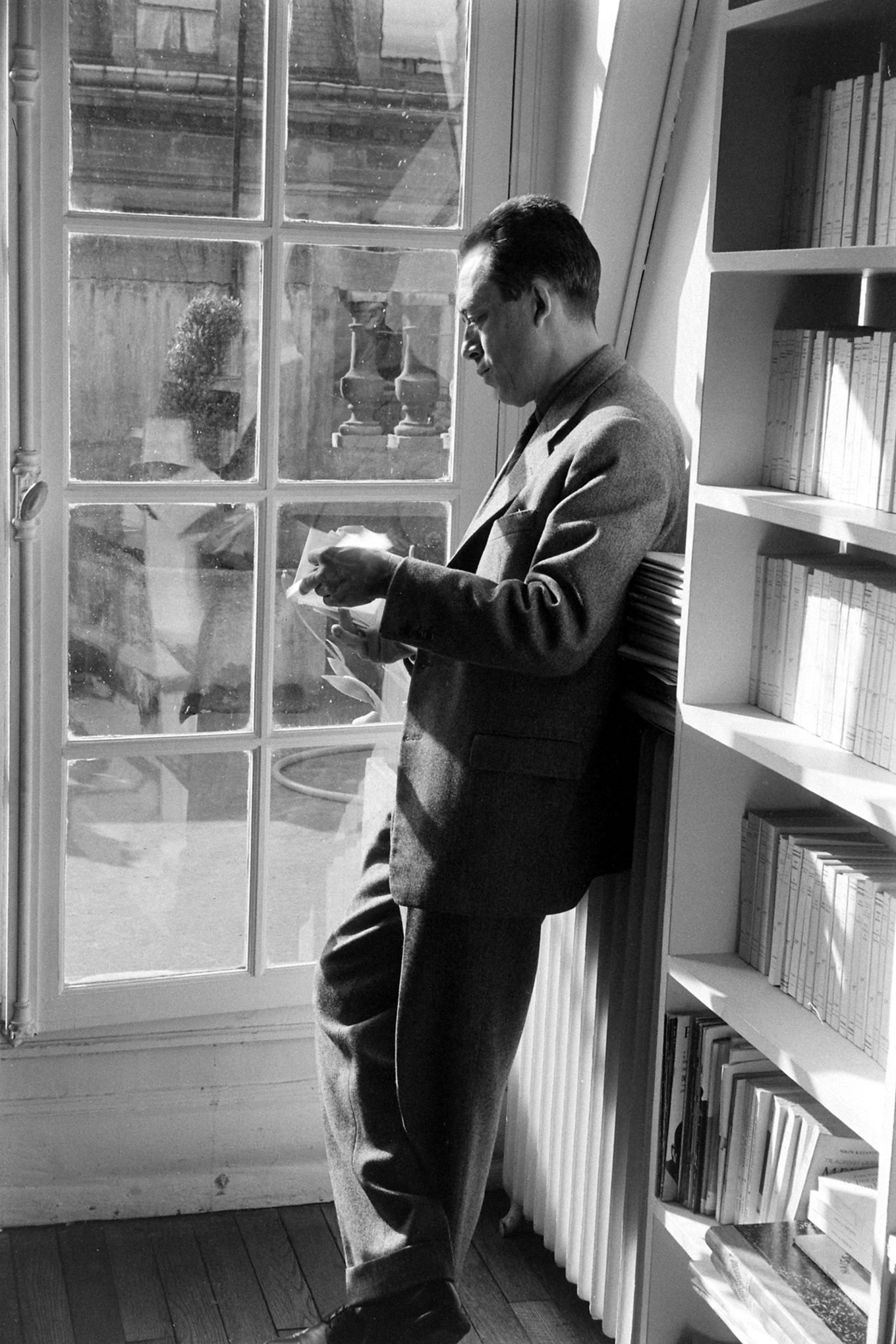

Across the globe, 191 countries have now been struck by the coronavirus or COVID-19 pandemic, a story and a very post-modern human tragedy, both poetic and political in a time of crisis. At this junction, few writers are mentioning Albert Camus’ novel that evokes so vividly and on such an epic scale the story we are currently living every day, “La Peste” or in English, “The Plague.”

Most of us read “The Plague” as teenagers in Junior High and High School, yet this novel, a classic of French literature, is almost nostalgic in these moments of pandemic. Millions of people who were asked to stay at home, are dusting off their bookshelves and looking for other Camus novels, like “The Stranger” and “Revolted Man,” but we should look to “La Peste” to find responses and better understand our situation on the literal level, as well as political, in the wake of the coronavirus crisis. A Camusian style is defined, as in “The Plague,” creating a feeling of fear and depression among people, obliging world leaders in a race against the clock to “ eradicate” and confront the coronavirus; through narration international and national media try to identify medical experts, doctors and policy makers who are launching preventive campaigns against the pandemic, starting in the 21st century plague’s ground zero, Wuhan province, China.

Those who remember Camus’ novel “La Peste” know that it took place in the western city of Wahran (Oran) in Algeria, a city that he lived in and loved, with his wife Francine. They both left the city of Algiers for a prohibited love (un amour interdit !) in Wahran.

The warning

Camus warned humanity and world leaders, after defeating fascism in Europe, that perhaps the world will be better off, prosperous and healthier, but his cautioning to us also includes a touching side, using the tragic epidemic in Oran, and social injustice in the great famine of the Kabylie region in the mid-1930s. This was Camus’ first cri-de-coeur – a report about misery and racial inequality, a result of harsh colonialist policies – that pushed him to move to France, and take a break from local journalism.

Later he published “L’étranger” (The Stranger), a book former American President George.W. Bush recommended that his fellow citizens read. One hopes he was not just reading about Westerners killing Easterners for no reason.

Millennial metaphor

Nonetheless, there is evidently another reason we should introduce “La Peste” to the millennial generation these days, to let it know that COVID-19 is not an unforeseeable pandemic, to be characterized on social media metaphorically as a matter between evil and good. It could represent something deeper about pestilences, both moral and metaphorical, that happened in Camus’ own lifetime as a teenager and a young rebel in Algeria, and later in France.

So it is worth reflecting on this tragic moment for humanity, what would the plague signify now for people and politicians, notably in France and in the U.S., whose political leaders failed miserably in their crisis management of this public health disaster? It is harming their credibility and their political future. Nowadays, “La Peste” tells the story of a different kind of plague: that of destructive materialism and its imperatives that Western and Eastern societies alike must obey.

For Algerian society, for instance, following the Red decade of dystopian groups’ terrorism and tragedy of state counterterrorism acts, 1992 to 2000 was the gravest crisis in Algerian post-modern history. But for all the suffering and the ultimate effects of fear and the socioeconomic depression of the Red decade, it was reassuring to once again stand united. Unfortunately, this led to an era of political stagnation and corruption, which manifested during the two decades of the ruling Bouteflika system.

Paradoxically, in the summer of 2018, the region of Blida, and its neighboring provinces, were hit by a cholera outbreak. The epidemic surfaced because of filthy streets across the province and within the city, that is ironically called the “City of Roses.” A lack of understanding about the transmission of cholera allowed the disease to spread. Seven decades later, it is idiotic that today people in Algeria and elsewhere still don’t take the coronavirus seriously – it’s covid-iotic!

Reflections

Today Camus’ novel “La peste” describes very well a society where the greed of world leaders leaves millions of migrants on their own across Europe and in the U.S. They are dying in the Mediterranean Sea and in the American desert in search of a better life that comes full of empty promises.

Camus saw no dichotomy between the emptiness that lies at the center of the immorality of politics and in the tragedy of morality. For example, the worryingly high morality in the Parisian suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis, located in Ile de France, the richest region in the country. Of course, this area is also the hub of France’s largest Maghrebian and Sub-Sahara communities. This department, known locally as le neuf-trois (93), is part of a fallacious storyline; that of white France and its ignorant media and arrogant elite who look at the department as the source of French malaise and the birth of France’s “multiculturalism.”

Several factors explain this progression, it is the second most populous department of Ile de France. The 93 is also the youngest, with 30% of the population under 20 years old. One factor, however, could be favorable. The fact that young people are less affected by the coronavirus than the elderly. But why does “La Peste” resonate so loudly to us today? Everything mankind does in a turbulent time is distracting to social behavior and even the nature of humanity means it’s very difficult to isolate one’s self, especially within families who are feeling that tragedy is only a way of assembling human misfortune, of subsuming it and thus of justifying it. What could humanists have to say about the tragedy that sparked from Wuhan?

The human brain reacts quickly to images and imagination. Is it able to detect signs of good and evil? If so, why would human beings be closed off? We need a new school of thought, which is likely to need much intention and action nurturing the poor and the voiceless through a new world order of citizens.

A new sort of thinking and the raising of awareness develops, as when Camus spoke about justice and his mother, he said, “I choose my mother.” He said this in a context, where through the liberation war in Algeria against Camus’ motherland, France, the Algerians made it clear they had enough of social injustice and epidemics. The nationalists decided to challenge France’s colonialism in Algeria and this existential question of France’s future in Algeria, later became the central tenet of evolutionary humanism that his friend, Jean Paul Sartre, set against Camus’ idealism and romanticism.

Camus is left to choose for good between his place of birth and the injustice of his imaginary patria (French military unit). Today, all states are preparing for all possibilities to prevent and fight the spread of the pandemic, which they will overcome with solidarity, discipline and patience.Though the mask of politics has fallen and the gloves are off, the world’s citizens are desperately wearing masks and gloves to prevent this invisible enemy, COVID-19, while remaining gripped with fear of socioeconomic depression and plagues of injustice.

* North Africa expert at the Center for Middle Eastern Strategic Studies (ORSAM)

Discussion about this post