Remdesivir has been shown to speed up recovery times for patients with COVID-19 in a major U.S.-led trial, becoming the first drug with proven benefit against the disease.

Here is what you need to know.

What is remdesivir?

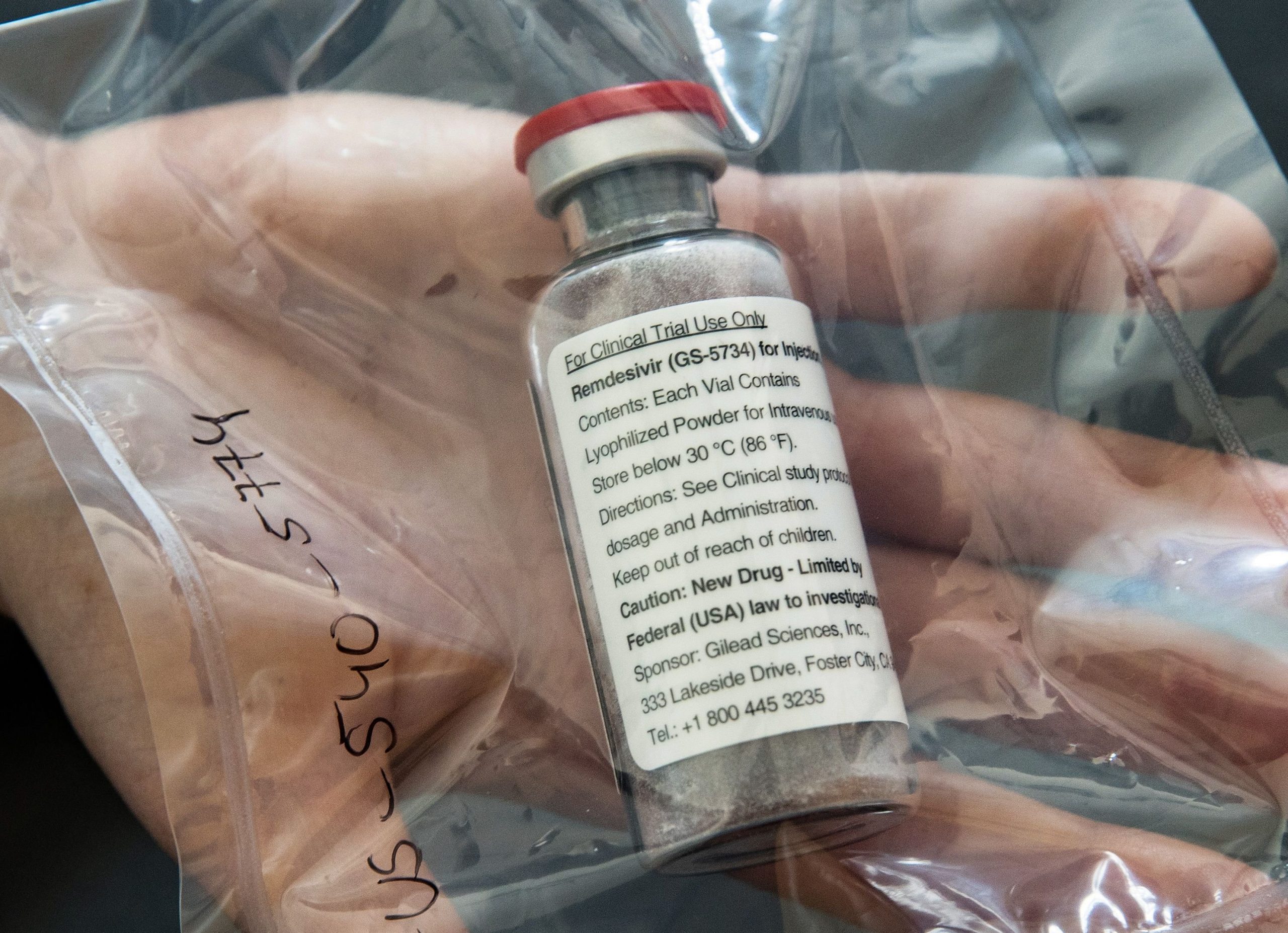

Remdesivir is an experimental, broad-spectrum antiviral medicine made by U.S. pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences that was first developed to treat Ebola, a viral hemorrhagic fever.

It showed early promise in a primate study in 2016 and was later rolled out for a major trial in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where it was compared against three other medicines. That study concluded in 2019 when it was discontinued because it did not boost survival rates as greatly as two monoclonal antibody drugs, which are lab-engineered immune system proteins.

In February, the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) announced it was dusting off remdesivir to investigate against SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen that causes COVID-19, because it had shown promise in animal testing against fellow coronaviruses SARS and MERS.

How effective is it?

The NIAID announced the results of its trial involving more than 1,000 people on Wednesday, finding that hospitalized COVID-19 patients with respiratory distress got better quicker than those on a placebo. Specifically, patients on the drug had a 31% faster time to recovery.

“Although the results were clearly positive from a statistically significant standpoint, they were modest,” Anthony Fauci, the scientist who leads the NIAID, told NBC News on Thursday.

In other words, while it works, it’s not a miracle cure. It is however considered a “proof of concept” that could pave the way for better treatments – just as the early medicines developed to treat HIV in the 1980s weren’t nearly as effective as those used today.

The results suggested remdesivir might lower mortality rates – from 11.7% to 8.0%, but this data is considered less reliable because it was above the cut-off of statistical significance.

Why have there been mixed results?

The findings from the U.S.-led trial were announced on the same day as the results of a smaller study were published in The Lancet, which found no statistical benefit from remdesivir.

This study involved just over 200 people in Wuhan, China, and was also a randomized controlled trial – considered the gold standard for evaluating treatments. Importantly, however, it had to be stopped early because it could not recruit enough patients, and was roughly five times smaller than the NIAID study.

“The numbers in the trial are too small to draw strong conclusions,” said Stephen Evans, a medical statistics expert at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

When might it be available?

Remdesivir has already been given to patients around the world, both in clinical trials and outside, with Gilead responding to “compassionate use requests” for emergency access.

Most recently, in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug for emergency use on coronavirus patients.

Since the medicine is complex to manufacture and is administered via injection, rather than a pill, there have been questions about whether supply could initially be limited.

The drugmaker company is also looking into potentially developing an inhaled formulation, but hasn’t given a timeline.

How does it work?

Remdesivir belongs to a class of drugs that directly attack viruses. It is what’s called a “nucleotide analog” that mimics adenosine, one of the four building blocks of RNA and DNA.

“The virus is not very careful about what it incorporates,” said virologist Benjamin Neuman, of Texas A&M University.

“Viruses usually try to go fast and they trade speed for caution,” he said.

Remdesivir sneakily incorporates itself into the virus’s genome instead of adenosine, which in turn short circuits its replication process.

Speaking during an earnings call Thursday, Gilead’s chief medical officer Merdad Parsey said that while patients who had had symptoms for less time seemed to respond better to the medicine, there also appeared to be some benefit for those who were more critical.

This is because the virus triggers an abnormal immune reaction called cytokine storm responsible for lung injury.

“By limiting the viral replication, you’re going to limit the inflammation, you’re going to reduce the number of people who develop lung injury, and you’re going to get them off the ventilator faster,” said Parsey.

Last Updated on May 04, 2020 12:48 pm

Discussion about this post