It took only months for the effects of the Arab Spring to spread across Syria, triggering an uprising that tried to topple regime leader Bashar al Assad, with support from the West, Turkey, and some Gulf states.

But supporters of the opposition forces from the Gulf states, excluding Qatar, didn’t want a triumph by the Muslim Brotherhood, which led the Arab Spring. The rivalry led to divisions among the opposition groups in Syria, as different groups were backed and influenced by different countries.

Disorganised opposition groups claimed control of some territories until the beginning of 2014.

Then Daesh evolved in Iraq, and Assad’s release of al Qaeda members from his country’s prisons led the group to expand to Syria. Daesh’s first stronghold in Syria was in Raqqa in January 2014.

The US’ priority of supporting the opposition changed, turning its focus from the Assad regime to Daesh.

Turkey has been a loyal supporter of the moderate Syrian opposition fighting against Bashar Assad since 2011.

Turkey, which has the second largest army in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), is also a part of the US-led coalition forces against Daesh. The coalition has been using Incirlik military airbase in Turkey for its operations against Daesh in Syria.

A shift in the US’ focus in the Syrian conflict led to the first dispute between Turkey and the US, even though both countries were still supporting the opposition and fighting against Daesh. The dispute was first apparent during the train and equip program.

Turkey and the US had agreed on training and equipping opposition groups in Syria in early 2015. Turkey’s aim was to train them to fight against both Daesh and the Syrian regime, while the US insisted on targeting only Daesh.

The dispute grew when the US decided to co-operate with another group in its fight against Daesh instead of the opposition groups—the YPG.

That changed the stance of global powers who were involved in the conflict that has killed more than 500,000 people and displaced many more, both internally and externally.

Turkey’s security concerns

Ankara and Washington have long been in co-operation with each other since the Cold War, and are allies in some international organisations, including the security alliance NATO.

The two countries’ co-operation in Syria was also expected, as was the case during the uprisings in other Arab countries, but it lasted until the US started to arm YPG militants in Syria and described them as “a powerful ally” against Daesh.

The decision, first taken by former president Barack Obama in late 2014, and followed by current President Donald Trump, angered Ankara, since the YPG is the Syrian extension of the PKK.

The PKK has been fighting the Turkish state for more than 30 years and has caused the deaths of more than 40,000 people through their attacks, including with suicide bombings targeting civilians.

Despite a clear statement by the former secretary of state Ash Carter that there are direct links between the YPG and the PKK, the US does not consider the YPG to be terror group, even though the PKK is designated as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the US, and the EU.

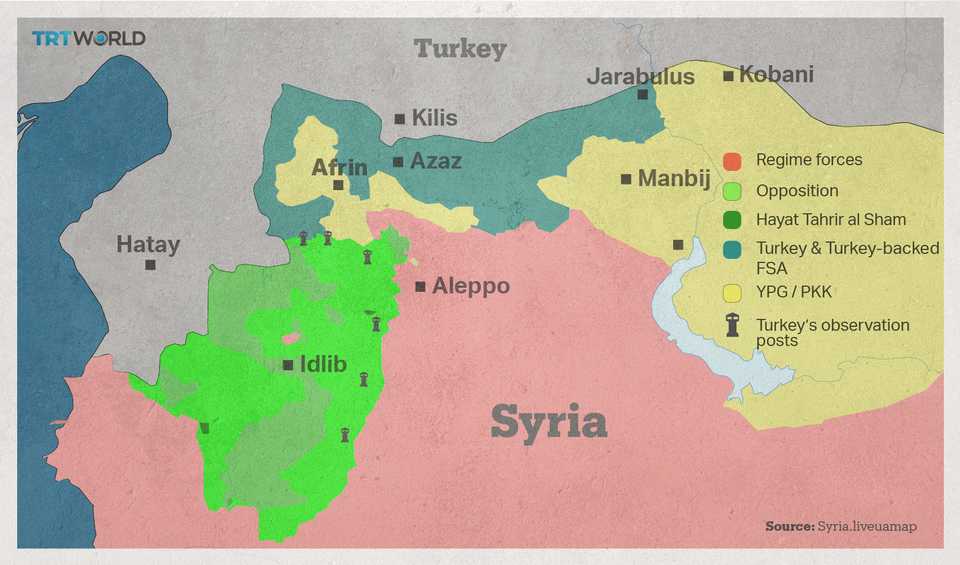

Turkey has repeatedly urged Obama and his successor Trump to stop arming and training the YPG. Washington said that the co-operation was only meant to be temporary until the defeat of Daesh. But despite the fact that the presence of Daesh in Syria had dwindled by the end of 2017, the US has still been supplying arms to the group. The YPG now controls nearly a quarter of the country.

However, the most exasperating move for Turkey came when the US announced it was working with YPG to set up a 30,000 people border force located along Syria’s border with Turkey.

Ankara considered the move to be a direct threat to its national security, bringing relations with the US to an all-time low. Ties were already strained after Turkey accused the US of sheltering the leader of the group that Ankara calls the Fetullah Gulen Terror Organisation (FETO).

FETO is responsible for the July 15 coup attempt that killed more than 250 people and injured more than 2,000 others in Turkey.

The US’ co-operation with these groups prompted Turkey to look for other allies in Syria.

Growing Russian influence in Syria

Russia had become an important actor in Syria since late 2015 when its air force began operations against anti-Assad forces, including moderate opposition groups.

Bashar Assad was losing ground against the opposition, but after Russia’s direct involvement, he reclaimed most of the territory he had lost, thus allowing him to retain his power.

Turkey’s interests in Syria have been different from Russia. Moscow supported the regime while Ankara was allied with the opposition groups. But their bilateral relations, including trade and the sharing of energy resources, were not affected.

That was only until a Turkish aircraft shot down a Russian jet that was targeting the opposition groups along Turkey’s border, violating Turkey’s air space in late 2015. That dampened relations between the two countries.

It was around that time when the US intensified its support for the YPG, and Ankara decided to focus on its own national security. Hence, in June 2016, Ankara and Moscow agreed to resolve their disagreements and work together in Syria.

Relations between the two states reached a peak level, especially after Turkey’s failed July 15, 2016 coup attempt when Russia reacted quickly and called Erdogan to offer support.

A month later, Turkey started its first military operation in Syria in the north, in an attempt to defeat Daesh, and to prevent the YPG from claiming more territory along its borders.

Russia controls the air space in Syria, which allowed Turkey to make deals with Moscow on ground and air operations.

Turkey’s second military operation in Syria’s Afrin started in January, again in co-ordination with Russia. This time, the operation directly targeted the YPG’s expansion.

Turkey and Russia’s co-operation wasn’t limited to Turkey’s Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Operations.

Late in 2016, Russia, Iran and Turkey gathered in Kazakhstan’s capital Astana to discuss how to bring an end to the conflict.

The trio has made significant progress on establishing de-escalation zones inside opposition-held areas in Syria to prevent more confrontations and civilian casualties.

Iran has been supporting the Assad regime, along with Russia, and has been powerful on the ground through its proxy militias. Iran’s involvement in the Astana talks dramatically changed the situation on the ground and helped to implement the de-escalation zones.

Later, the trio started talks in Sochi to discuss the future of Syria. The first summit of the three leaders was held on November 22 in Sochi. The next one is expected to be held in Istanbul on April 4.

Disputes over the future of Syria continue

Iran and Turkey share a border, as well as their concerns over the YPG. YPG/PKK is not limited to Syria and Turkey, the Iranian affiliate of the group is called the PJAK.

A possible division of Syria, which could create an autonomous region in the north for the YPG, would also pose a direct threat to the national security of Iran and Turkey.

But it hasn’t stopped Iran’s proxies and regime forces from helping the YPG with reinforcements in Afrin.

Russia also supported the YPG diplomatically during the Astana talks. Its soldiers were based in Afrin together with the YPG militants.

But Russia was more sympathetic to Turkey’s security concerns over YPG presence in Syria, according to officials Ankara.

Despite the fact that Ankara still considers Assad to be an illegitimate leader who has contributed to the killing of millions of Syrians—considering its national security interests and also Russian and Iranian influence in Syria—Ankara has developed better relations with the two countries than its Western allies have.

The three countries have the same approach for the implementation of a democratic election after the war ends, for Syrians to be able to chose their own leader, as well as for the territorial integrity of Syria.

Discussion about this post