“When we would travel between Damascus and Latakia on vacation with my family we would stop at a famous sweet shop called Tayyba,” says Mustafa al Homsi*, who now lives in Istanbul working as a tech developer.

“It was a tradition for every Damascene family travelling to Latakia to buy some sweets,” Homsi tells TRT World, recalling life in Syria before the revolution.

An activist during the height of the Syrian revolution, for Homsi the road to Latakia now has a different resonance and the once-famous sweet shop Tayyba, in the strategic town of Al Nabk just of the M5 and about 90km outside of Damascus, now lies in ruins, bulldozed by the Assad regime.

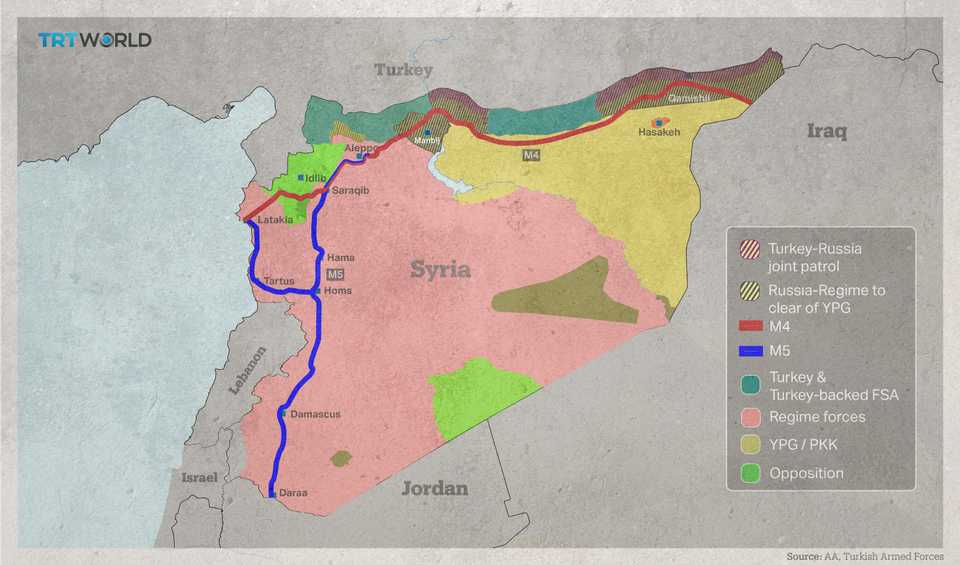

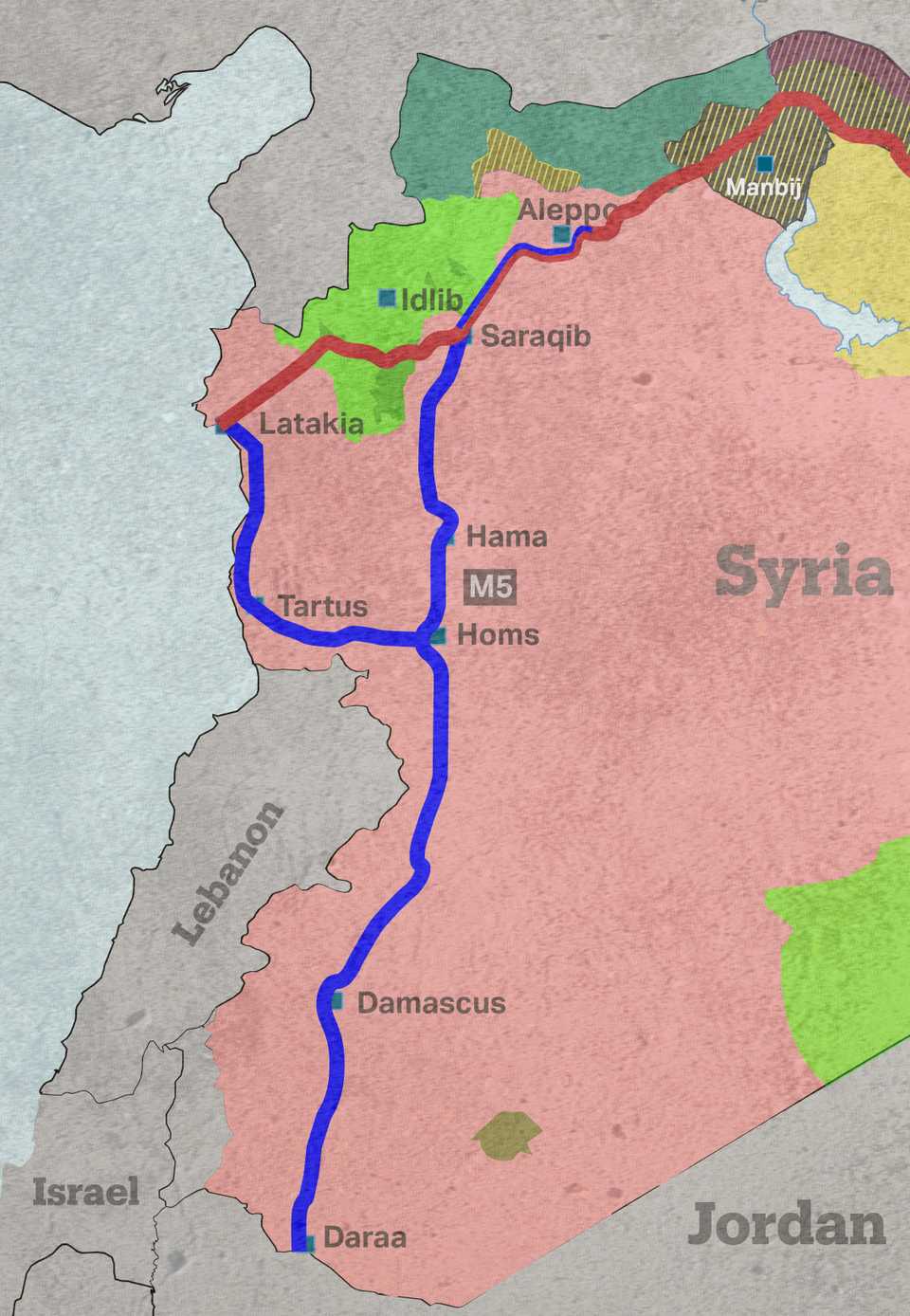

Many Syrians call it the “international highway” – a 474km stretch of road and a critical artery, known officially as the M5, connecting the entire breadth of western Syria from the Syrian-Jordanian border to Aleppo.

“Whoever controls this road can control the commercial movement between these two cities [Damascus-Aleppo],” Anas Tracey, a Syrian reporter living in Idlib, tells TRT World.

The M5 highway is also critical in linking Syria with the Jordanian border and in the recent past to Turkey’s southern city of Gaziantep, an industrial hub and a centre for imports and exports.

The Assad regime at one point had lost control of vast sections of the road to a smorgasbord of Syrian groups fighting to overthrow the family that has ruled the country with an iron fist for the last 40 years.

Functioning as the backbone of the national road network, the M5 connects cities that have also become internationally known as sites of brutal destruction.

The city of Douma, just outside of Damascus, is located close to the M5 motorway and was the site of at four chemical attacks as the regime sought to take back control before finally falling in 2018.

The siege in Hama again saw the regime bludgeoning a city into submission, one that had already been the scene of a brutal massacre in 1982 by Hafez al Assad, the current ruler’s father. The Assad regime encircled vast sections of the Hama countryside that surrounds the highway.

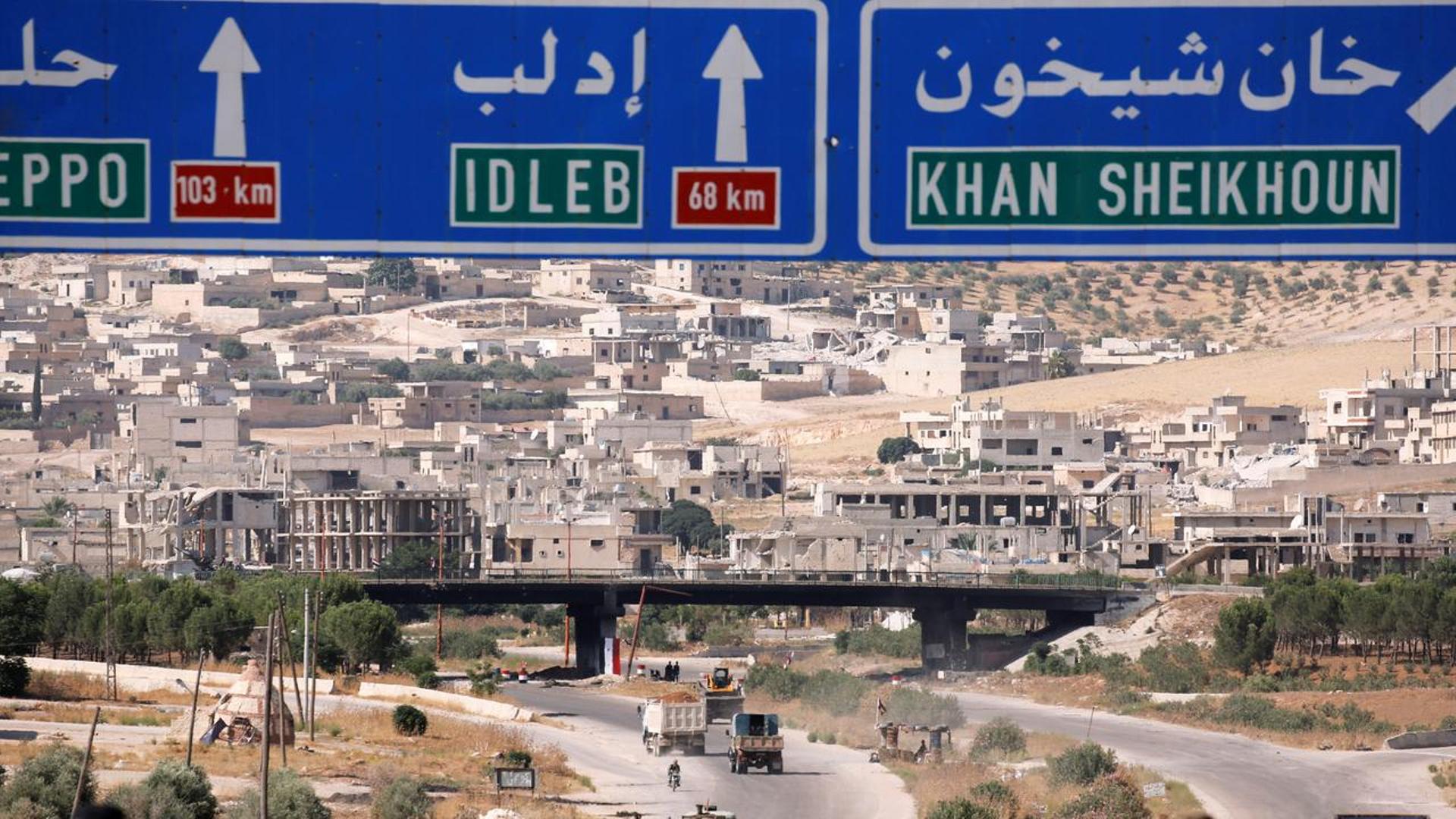

Even small towns like Khan Shaykhun, south of the Idlib governate, became internationally known due to a regime chemical weapons attack which killed 89 people and left more than 500 injured. Were it not for the M5 motorway running directly through the town it may have been spared.

The M5 highway has been a critical road map of destruction as the regime seeks to establish a semblance of sovereignty over Syria and, more importantly, to connect to Aleppo, formerly an economic hub.

“This highway has economic importance because it connects the city of Aleppo, which was the industrial capital, with Damascus and also continued to the southern border that was the main highway for transit trade, whose revenues were previously estimated at $3 billion annually, from 150,000 trucks,” Kinda Hawali tells TRT World from Idlib, one of the last bastions of the Syrian resistance.

The M5 motorway has further critical extensions to the port of Tartus, home to Russia’s only naval base in the Mediterranean, and Latakia, the home of the Assad family clan and Russia’s largest electronic eavesdropping post outside its territory.

Beginning in December 2019, the Assad regime moved aggressively to conquer the M5 section of the road that is still within Idlib, making it difficult for Damascus to tighten its grip on Aleppo, a city it conquered in 2016.

Of such critical importance was the M5 highway that between 2012 and 2016, regime forces in Aleppo could only be supplied through airdrops or new hastily built backroads.

“It is difficult for me to accept that both Russia and the Assad regime want the highways for industry or for an economic purpose, there is no industry in Syria since 2011, most of the factories were destroyed by bombing, no fuel in Syria now, no agriculture as before,” says Hawali.

The recent Assad regime offensive and capture of Saraqib, a town at the intersection between the M4 and M5 in Idlib province, was a strategic coup.

Not only did the regime open up a critical part of the M5 motorway leading to North Aleppo but also west to the M4 highway leading to Jisr Al Shughur one of the largest cities in Idlib province and still under rebel control from there to Latakia.

Beyond the strategic importance of the highway for anti-regime rebels, controlling the M5 would have meant the physical collapse of the authority of Syrian regime leader Bashar al Assad.

Lina Shamy, a Syrian activist, studying and living in Istanbul speaking to TRT World, believes that as long as the regime did not exercise “control over this international highway, it meant that the revolution succeeded in weakening the regime’s domination all over Syria”.

The grinding military machine of the Assad regime oiled by its allies has resulted in Damascus becoming close to taking back control of Syria, with the support of Russia and Iran and “marketing the regime as the key to stability” and to “regain legitimacy in the international community” adds Shamy.

Even as the Assad regime connects the M5 with Aleppo, it won’t be for economic reasons.

“What the regime and Russia really want is to push the Syrian opposition into a corner and make it choose between death and surrender – both mean the same thing,” says Hawali.

The Assad regime’s recent capture of the city of Ma’arrat Al Nu’ man along the M5 highway, previously one of the few places still under rebel control in Idlib, suggests that Damascus and its backers want to push rebels and civilians alike to the countryside in their bid to control urban centres.

“Russia is trying to rearrange things in Syria to convince the world that the problems in Syria are over and that Assad won against the ‘terrorists’,” adds Hawali.

In rebel-held Idlib however, the so-called “terrorists” that bear the brunt of Assad’s liberation are civilians. The majority of the 3.5 million population in Idlib are displaced refugees from other conflict areas in Syria and no longer have anywhere else to go.

“It became a small Syria without Assad,” says Shamy describing Idlib and the surrounding provinces which have yet to fall into the clutches of the regime.

The international community has largely remained silent as a humanitarian crisis unfolds in Idlib – an impending crisis that has been clear for years.

As the last stronghold of the Syrian revolution, the continuous bombing “not only threatens the lives of the people living there but also threatens the hope of democracy and freedom for future Syria” says Shamy.

The Sochi agreement of September 2018 was meant to avert an assault by the Assad regime on Idlib. A memorandum of understanding between Russia, Turkey and Iran was signed that would have opened the M5 and M4 motorway to traffic while also maintaining the status quo in Idlib.

The Assad regime and its allies, however, have used the Astana and Sochi process to freeze different conflict areas and go after rebel areas one area at a time.

“It’s not just about the M4 and the M5 highway,” says Nour Abdulrahman Hallak, a civil society activist based in Idlib. “All the armed opposition, activists and civilians who refused to live under the Assad control moved to Idlib.

“If the regime controls these two highways, it means that the regime defeated the opposition politically and on the ground.”

Even as the Assad regime consolidates its hold over critical infrastructure, the country is unlikely to ever return to the same social and political borders it once had.

Many of the remaining opposition-held areas, whether in Afrin, Idlib or the outskirts of Aleppo, hold ordinary Syrians who don’t want to live under the Assad regime and the brutality of its secret service and may not want reconciliation. Syrians living in regime-recaptured territories previously opposed to Assad have repeatedly faced reprisals from the Syrian regime.

Whereas the Assad regime has seen its resources depleted, critical infrastructure destroyed, human capital has fled or been killed. Neither Russia nor Iran have the financial clout to rebuild Syria.

Damascus’s hold over cities recently conquered along the M5 motorway is also tenuous. Protests in the regime-controlled city of Deraa against a statue of Hafez al Assad being erected suggest that it’s not business as usual, irrespective of how brutal the regime is.

*Mustafa al Homsi’s name has been changed for security reasons.

Discussion about this post