ISTANBUL — When Guliz Erginsoy was a young girl, she often pointed at her grandfather, Huseyin Atif Bese’s torso and asked, “where are those scars from?” Bese would answer, “oh, these are bird bites,” and change the conversation.

Bese served as an ordinary soldier for four years on western and eastern fronts of the former Ottoman Empire. Six decades later, as an old man in his 80s, he never spoke about what he had experienced in World War I.

“Most probably he was traumatised,” says Guliz, who’s now 62-years-old. “He also didn’t want to affect his son and later on his granddaughter [Guliz].”

Guliz’s most memorable childhood memory with her grandfather is that she often sat on his lap, combing his hair with lemon cologne. In his calm and quiet demeanour, he would let her play with his hair. But there was something in the house that always evoked Guliz’s curiosity. Three leather-coated books stacked in the library Bese had built for his son.

At times Guliz would ask her father if she could have a read of the books. He would let her do so but with utmost delicacy and care. “It was in Ottoman-Turkish. His calligraphy was marvellous, now I understand it, of course. His drawings were marvellous. He was a man of talent and craft.”

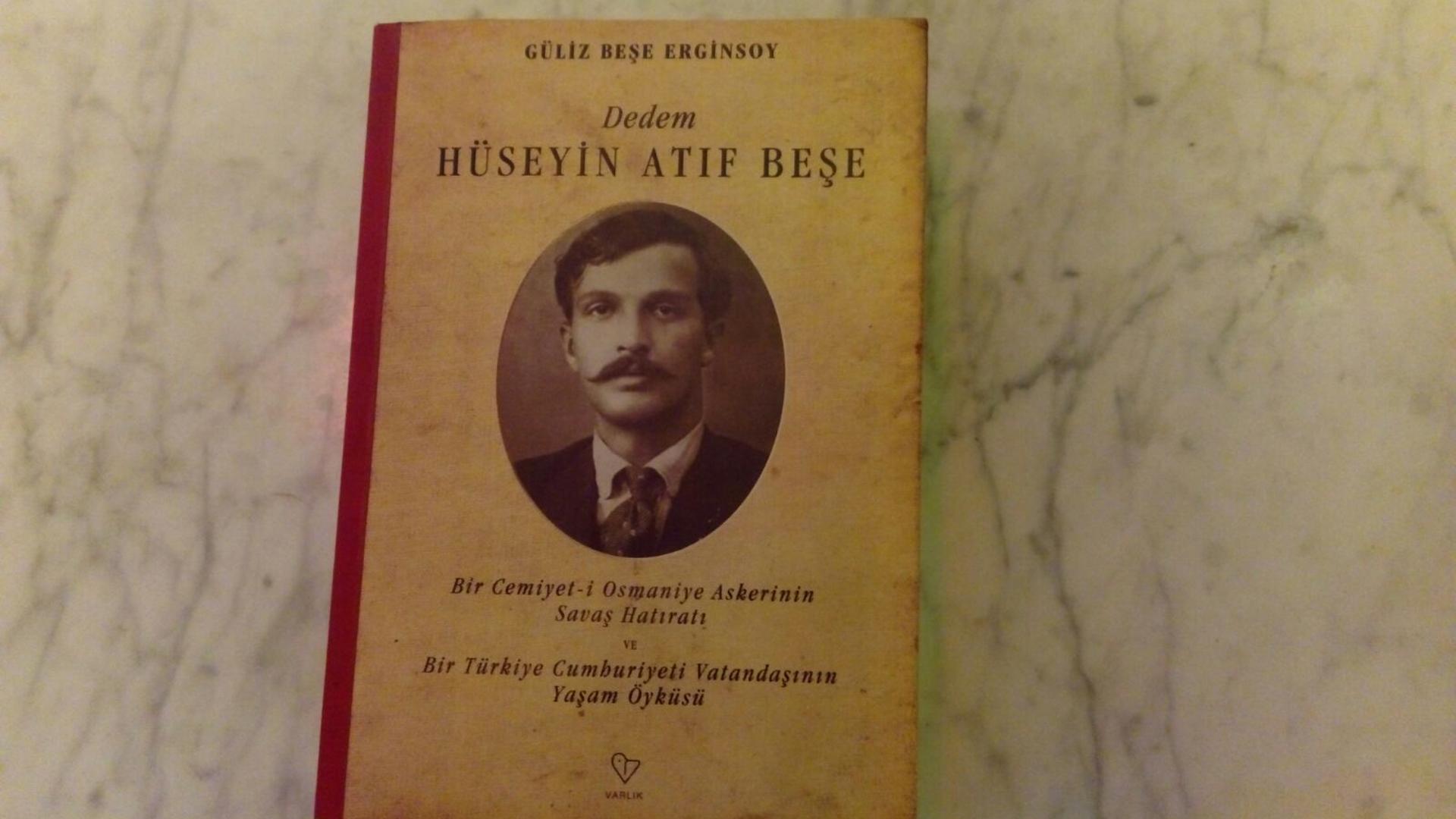

In the early 1980s, Bese passed away, leaving behind his memories and experiences drafted in books. With her grandfather gone, Guliz decided to compile the books. She wanted to preserve Bese’s brave account of the Great War and share it with her son.

Bese’s account is one of the most authentic memoirs of the war. From an ordinary soldier fighting for the former Ottoman Empire, his narrative is one of the neglected perspectives of World War I. The war has almost always been narrated through Western eyes. A century later, as we observe the 103rd anniversary of the decisive Gallipoli Campaign, Bese’s memoir serves as a terrific work of non-fiction, a testimony to what was happening on the other side of the battleground. The side, which was named as “the sick man of Europe” and largely ignored, demonised, and accused of massacres and a genocide.

After reading through her grandfather’s notes, Guliz came to an understanding that violence during the war existed on all fronts. It was reciprocal, she says, a deadly cycle that affected the citizens of the Ottoman Empire as much as it did the allied forces and their regional supporters.

Her grandfather Bese was born and raised in Anadolu Kavagi. The neighbourhood still exists on the Asian side of modern day Istanbul. Bese’s forefathers had moved there from Istanbul’s Black Sea region at least 500 years ago. A seaside village that is abundant with traces of history, Anadolu Kavagi has always been a key strategic position and a heavily guarded territory.

One day in the beginning of the Great War, Bese and his two friends were sitting in a traditional coffee shop in Anadolu Kavagi. They were restless young men, waiting to be officially deployed to Gallipoli, where allied forces, or Anzacs, were expected to launch a naval war against the Ottoman Empire.

Instead of waiting any further, they decided to join the war. During his time as a soldier on the empire’s eastern and western fronts, Bese wrote extensively about his experiences.

“If there is anything I have seen or understood here, it is snow. One and a half or two meters deep,” Bese wrote. “I shiver in cold and am unable to sleep at night. That is what I know. What I have seen is bodies of soldiers lying frozen in the snow. People are so hungry that they have slaughtered a cat and eaten it, or eaten their shoes.”

Guliz still has vivid memories of Bese. Though Bese’s life history binds the family together, Guliz and her father do not talk about the war. Even when she narrates Bese’s story to TRT World she quickly lightens up the moments of melancholy with her bright smile.

Despite facing countless tragedies, she says, Bese had a unique “sense of humour.”

For Guliz, World War I is deeply personal since she was raised as a granddaughter of a man who braved deadly winter spells and hunger and disease for his devotion to his homeland.

The soldiers who fought at the front lines returned home with trauma. They had one reason to be content with, however. And that was the formation of the Turkish Republic, a nation state that emerged out of countless sacrifices, promising its people freedom and dignity. But Guliz believes that because of the lack of diverse accounts in World War I, Turkey has always been misjudged by most of its European neighbours.

“Since Europe is a Christian and we are a Muslim country, we will always be alien to them” Guliz says, referring to Turkey’s long-standing bid to join the European Union, which is now at the brink of collapsing.

Starting from 1914, the Ottoman Empire fought against Allies on several fronts: Sinai, Palestine, Mesopotamia, Caucasus, Gallipoli, Kut al Amara, and other regions. The empire was allied with central powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria, which provided some logistical and military support to them.

While European armies were fighting a modern war backed by its industrial progress, the Ottoman Empire was fighting it with pre-industrial conditions. The Ottoman soldiers did not have warm clothing, decent accommodation, transportation, health services and they often suffered from food shortages.

“Last night I couldn’t sleep.” Mr Bese would often write in his diary. “My feet were almost frozen. The coal is finished, and with the roads closed there is no chance of obtaining more. Today we are shivering in the open without a fire.”

War and famine left a deep impact on the civil population, affecting the morale of the Ottoman military too. Recruiting soldiers was a difficult task. The empire was unable to support its own army, let alone addressing their trauma.

Prior to engaging in World War I, the empire was recovering from the Balkan Wars: malnutrition, disease and hunger were widespread within Ottoman lands. Peasants were taken to military service and their fields were left to older people, women and children. As a result, several famines struck the region.

Under these circumstances, civilian and military casualties were tremendous on the Ottoman side. The population of the empire was 20 million at the beginning of the war and it dropped to 15 million between 1914 and 1918, according to the book Ordered to Die by Edward Erickson.

Among those five million, around 700,000 were military casualties who died either in the battleground or because of diseases caused by poor sanitary provisions.

Over four million Muslim casualties are completely missing from the annals of history. The carnage isn’t known to the world mainly because of low levels of literacy in the Ottoman Empire or one-sided narratives coming from the West. The archival evidence of survivors indicates that at least 500,000 Muslims were massacred between 1914-19. Given that, some groups under foreign protection formed gangs and militias and revolted against the Ottoman Empire, killing tens of thousands of people.

In northeastern Anatolia between 1916-18, when Russia and their Armenian proteges occupied the Ottoman lands, large-scale massacres were carried out against Muslims. As the war affected the population of the then-Ottoman Empire, it also impacted Turkey’s future.

“The impact was primarily on the composition of the population” says Guliz. “A lot of men died, single women raised their children alone and many single-parent families emerged. Those families struggled, facing financial troubles, to have a stable family and provide education to their children. It had a domino effect on other aspects of life.”

After the end of World War I, a new discourse emerged from the West. As Britain and France secretly redrew the Middle Eastern map, dividing it into several nation states, the new formation was presented as a viable solution to secure long-lasting peace in the region. But it was an illusion. The Middle East without the Ottoman Empire as imagined by the West did not turn out to be a peaceful one. A century later, the region is still highly contested between various regional and international powers. The Great War ended up impacting the composite culture of the Middle East that was secured under the Ottoman reign.

In Bese’s diary, one thing comes out strongly: the war did not bring anything but plunged the entire region into death and destruction.

Though Bese died as a man with several battle scars on his body and soul, he was able to accommodate his protest against the war.

“War is actually an objection,” Guliz, his granddaughter, says. “Objection in the sense of disrespecting human rights, disrespecting peace.”

Discussion about this post