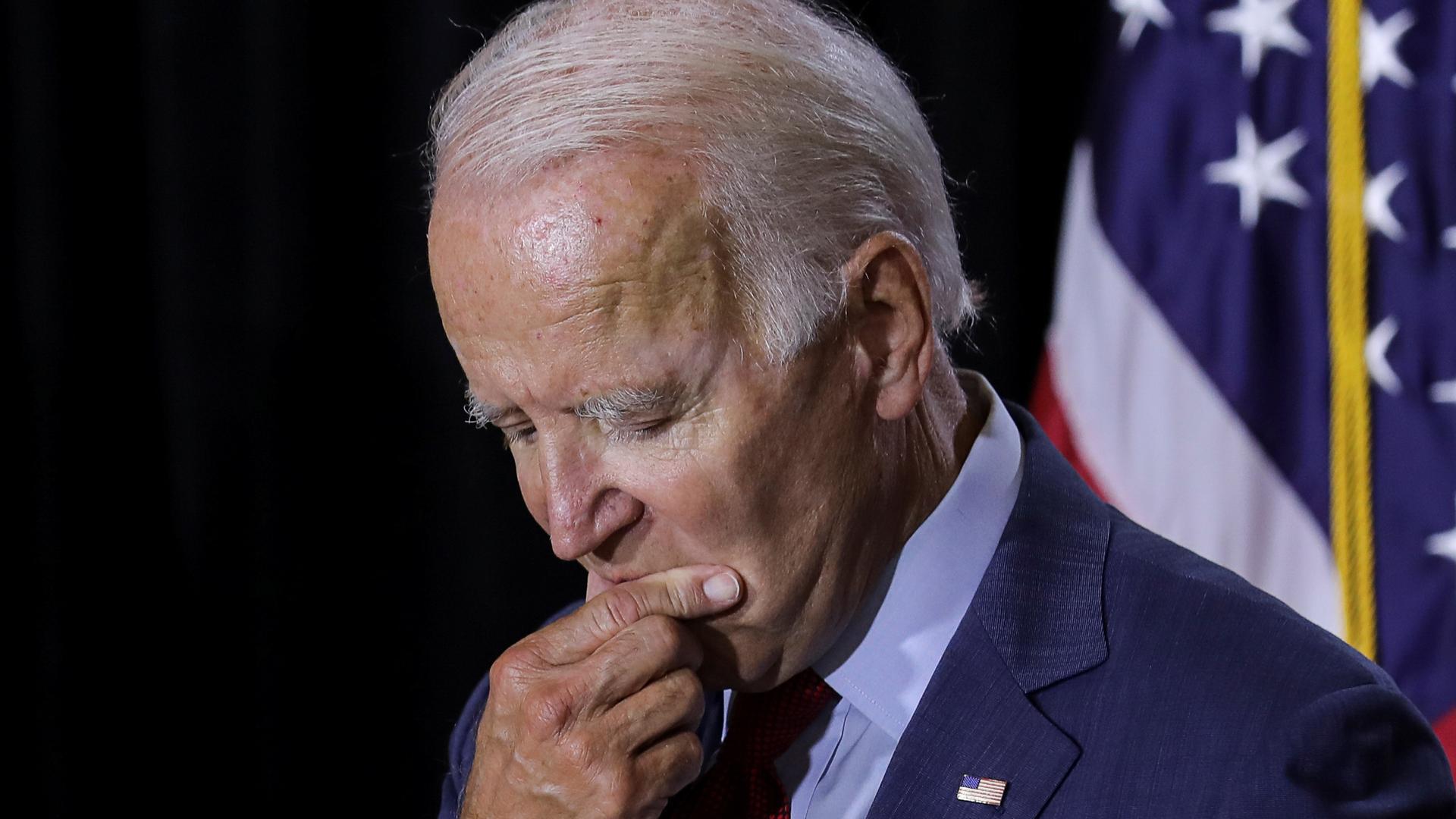

Joe Biden, the US presidential candidate for the Democratic Party, has made numerous gaffes during his vice presidency, as well as in the course of his presidential run against incumbent Republican President Donald Trump.

However, for some, his comments about Turkey, and the conditions of its Kurdish population, appeared to beat all of his previous gaffes. He claimed the country’s Kurds “wanted to participate in the (political) process in their parliament” in an interview withThe New York Times recorded in December last year.

Turkey’s Kurdish-origin citizens have represented their respective provinces for different parties in parliament since the beginning of the Republic’s founding.

Beyond that, Turkey’s Kurdish-dominated parties, some of which have ties with the PKK, a terrorist organisation, have also a long history of participating in parliament since the late 1980s.

Before Kurdish-dominated parties, Turkey has been led by prime ministers, presidents and parliament speakers with Kurdish roots, which included Turgut Ozal, Bulent Ecevit and Hikmet Cetin, serving on both sides of the political spectrum.

The current Republican People’s Party (CHP) leader, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, is originally from the Kureysan tribe located in Turkey’s eastern province of Tunceli. The tribe’s native tongue is Zazaki, a language with close links to Kurdish. Kilicdaroglu considers himself Turkmen.

The CHP was established by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founding father of Turkey.

“He (Biden) appears to be living on Mars not on the Earth as he speaks about Turkey and its Kurds,” says Mehmet Bulovali, an Iraqi-Kurdish political analyst, who was born and grew up in Kirkuk, an oil-rich city regarded as Jerusalem for the Kurds.

During the interview, whose resurfacing in Turkish media outlets coincides with the emergence of several new parties that trace their roots to the AK Party as the opposition accelerates its criticism of the government, Biden’s main Turkey focus appears to have been over two things: ousting Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the Kurdish question.

“What I think we should be doing is taking a very different approach to him now, making it clear that we support opposition leadership,” said Biden during the interview.

But Bulovali also thinks that Turkey’s assertive Eastern Mediterranean policy is one of the main reasons for the video’s recirculation across social media and other platforms.

“It’s related to what happens in Eastern Mediterranean,” the analyst says. Turkey’s increasing presence in the region has triggered regional powers, resorting to tactics like resurfacing the Biden video to threaten Erdogan to backtrack from its Mediterranean policy, according to Bulovali.

In the video, Biden mentions the Eastern Mediterranean as a factor for his opposition to Erdogan.

“I think it takes an awful lot of work for us to be able to get together with our allies in the region and deal with how we isolate his (Erdogan) actions in the region, particularly in the Eastern Mediterranean in relating to oil and a whole range of other things which take too long to go into,” Biden said.

Erdogan and the Kurds

While Biden portrays Erdogan as someone who is an enemy of the Kurds, Bulovali thinks the opposite. “In this region, if the Turks and Kurds stay together, it happens due to Erdogan’s presence and approach,” the Kurdish analyst says.

Under Erdogan’s leadership, Turkey launched an initiative in 2009 and reframed it in late 2012 in order to disarm the PKK, drawing support from both Turkish and Kurdish populations. In mid-2015, the “resolution process” collapsed as the PKK refused to abide by the processes of disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration.

While the resolution process failed, Turkey’s political reforms on the use of the Kurdish language in the public sphere and other rights have stayed intact. At the same time, much of the PKK presence in Turkish borders have been eliminated through consistent military operations since 2015, bringing security to the country’s eastern and southeastern regions.

Biden, though, appears to have no understanding about the transformations within Turkey, especially as the country’s Kurds have increasingly expressed their hesitation and opposition over the PKK’s terror campaign and its scorched-earth policy.

“People [particularly, Turkey’s Kurds] have been tired of PKK’s armed campaign. In the past, I would not hear much that people were escaping from the Qandil mountains [the mountain headquarters of the PKK leadership in northern Iraq]. But currently, every day we see escape stories of PKK members from there,” says Bulovali.

“This is important. It’s not a simple incident. If people escape from the PKK, they do it because of what they see in practice,” he opines.

But as PKK members abandon the terror group, Washington continues to support the YPG, the Syrian wing of the PKK, across northern Syria in the name of fighting Daesh, ignoring its NATO ally Turkey’s warnings.

US support for the YPG began in 2015 when Biden was Barack Obama’s vice president.

PKK, which is recognised as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the US, the EU and NATO, has led more than three-decades-old terror campaign against the Turkish state, costing deaths of tens of thousands of people including children and elder citizens.

Discussion about this post