ISTANBUL — Hamza Zawba, a former spokesperson of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, sips tea in a Turkish cafe in Istanbul’s Yenibosna neighbourhood.

Zawba comes across as a good-humoured man. When I asked him about the date of his first arrival in Turkey, he brushed aside the query saying — “Does it matter? Let’s talk about politics and Egypt.”

I asked him about his age and he countered, “What’s your age?”

I told him I was 43 years old. He said, “Add 15 more years to your age and you’ll figure my age.”

Beneath his humour lies layers of anxiety. Zawba frets over everything. He’s fretting over the future of Egypt. He’s fretting over Sisi’s spies. At the same time, he feels something revolutionary is going to happen in Egypt.

“People are going to explode,” he says.

Zawba now hosts a show at Mekameleen, one of the most popular TV channels critical of Sisi’s government, peddling pro-Brotherhood views.

Since Sisi comfortably won the recently concluded elections, which was one sided, with most of the opposition either in exile or stifled with brute force, Zawba argues that Sisi’s rule won’t last for long.

Musa Mustafa Musa, the lone challenger in the election, declared his support for Sisi’s second term prior to the polls. In January, Sami Anan, a former army chief, had announced his run against Sisi, but he was arrested soon after the announcement and continues to be in detention. Another contender, Ahmed Shafik, a former top-ranking military general who also served as prime minister, also withdrew his candidacy as the election drew closer.

“If a general runs against another, something should be wrong about that country,” Zawba says.

The country’s opposition, most of which operates in exile, called for an election boycott.

“What’s going on in Egypt is beyond any imagination. It’s unthinkable for a wise man,” Zawba says, betraying a hint of frustration.

More than 66,000 people have been imprisoned in Egypt on terror charges. At least 55,000 of them are formally or informally linked to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The country’s senior most journalists were summoned to follow a diktat on how to portray Sisi and his policies in public. More than 10 TV channels and several dozen news websites have also been banned by the regime since last year.

The regime has even prohibited the clacker toy for kids, which is widely called as “Sisi’s testicles.”

“These steps are unprecedented in the history of Egypt, making Sisi’s oppression worse than that of [Hosni] Mubarak or even [Gamal Abdel] Nasser,” who were the former presidents of Egypt, according to Walid el-Sheikh, an Egyptian journalist based in Berlin.

Zawba compares today’s Egypt with countries like Romania under Nicolae Ceausescu, Serbia under Slobodan Milosevic, and Libya under Muammar Gaddafi.

“In Egypt, there are now one million checkpoints. But the military is not able to finish its security operation in the Sinai peninsula. At the same time, we have $88 billion debts. The current regime has failed in both its economic and security policies,” Zawba says.

Though Sisi’s International Monetary Fund-led harsh financial policies claimed to ease economic hurdles, the ground reality is different. Egyptians complain of price rises and inflation. The Egyptian pound has lost half of its value under Sisi’s economic reforms, affecting the country’s middle class.

Most of Sisi’s cabinet posts have been filled by the generals loyal to him. Zawba is astounded to see even the country’s deputy health minister has to be an army general.

Obey or leave

Zawba recalls the state of media in Egypt, most of which is singing the praises of Sisi. He remembers the time when a panelist in one of the pro-regime TV shows told his host that “we are suffering.” “The host retorted, ‘If you are not satisfied here, get out of this country’,” says Zawba, shaking his head in disappointment.

After the Rabaa massacre in August 2013, when the security forces killed more than 800 people, protesting against the coup, Zawba and several hundred critics of Sisi were left with no other option but to leave their country.

“I was in the Rabaa square to protest the coup,” he says. “Our plan was to defeat the military coup in a peaceful way. But the regime had other plans.”

Zawba left Egypt and moved to Qatar, where he often appeared on Al Jazeera TV channel as a political commentator. In 2015, he moved to Turkey. Soon after, he took up a presenter job at Mekameleen TV, which he says was launched by some “like minded” Egyptians in 2014.

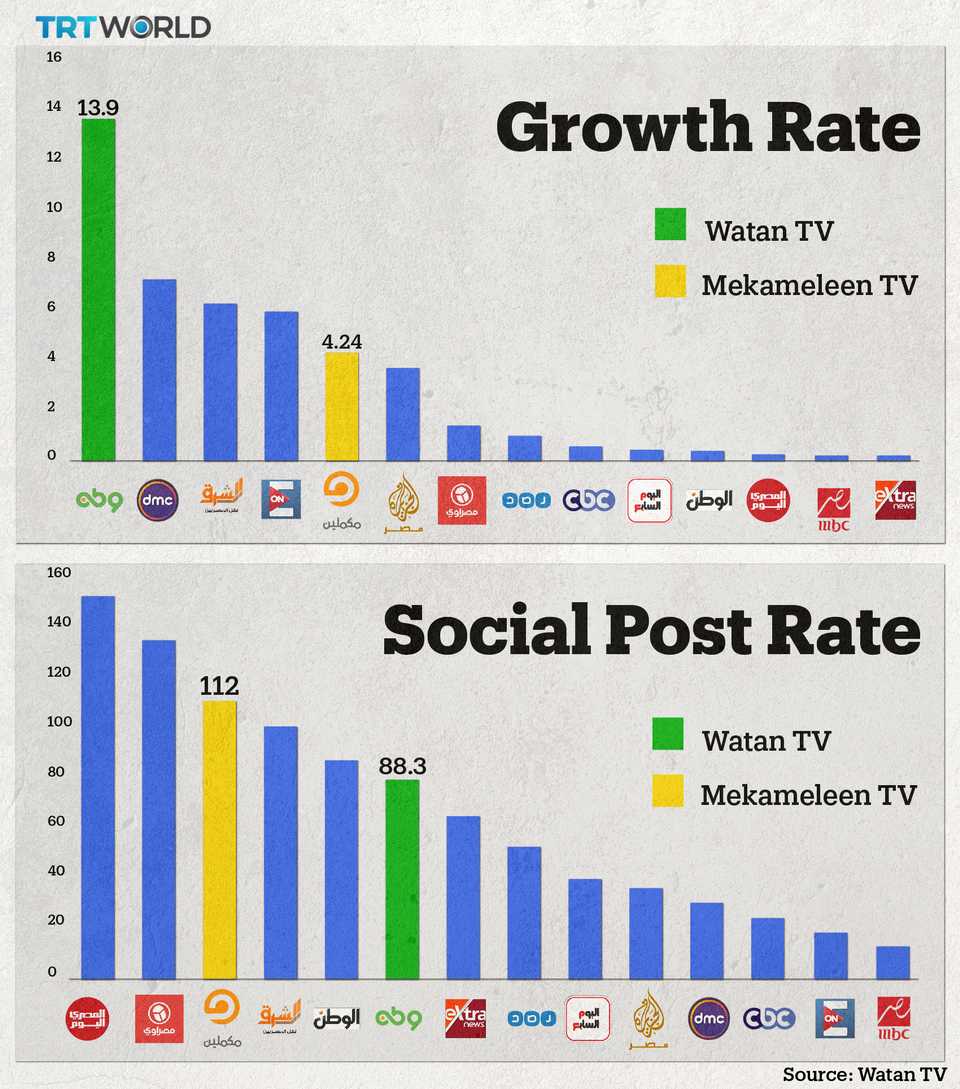

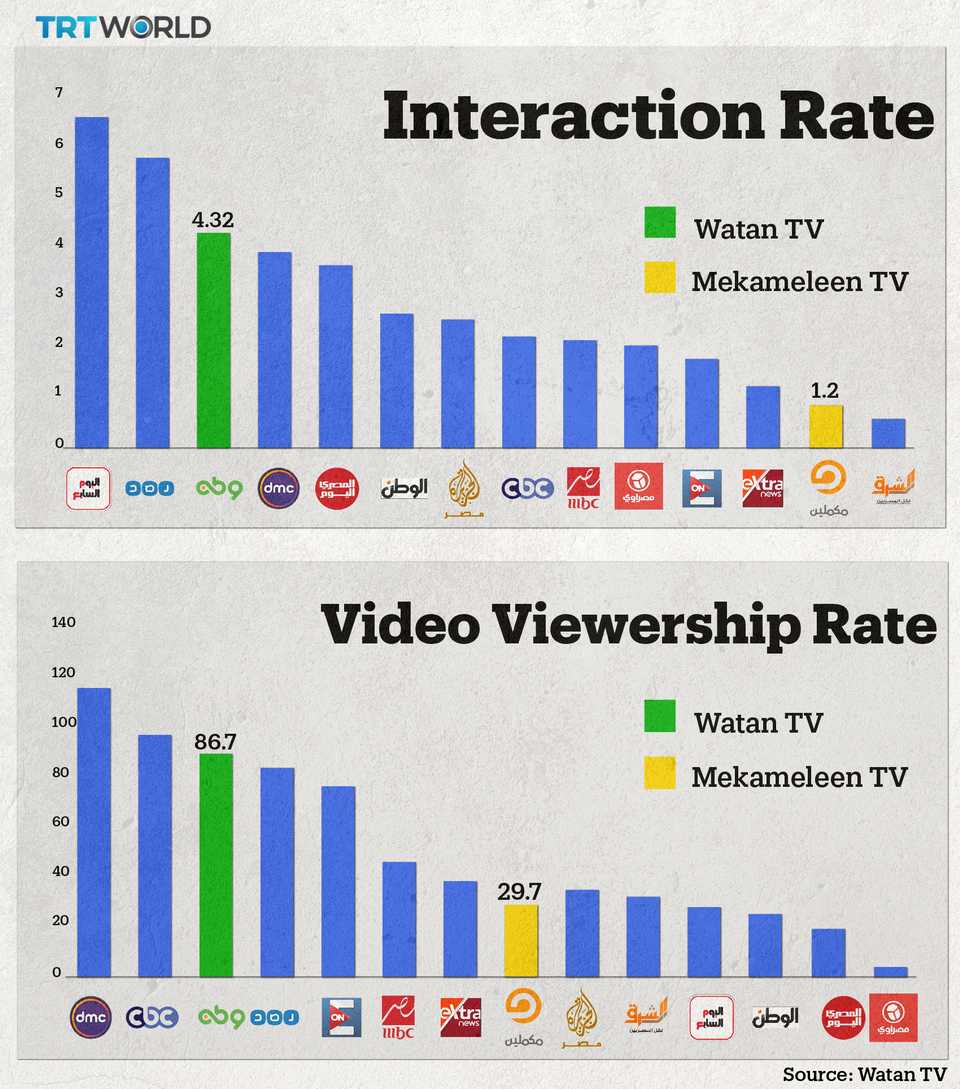

“We are with the revolution, and we need to restore our revolution. That’s the message [of our program],” Zawba says. “We are the second most-watched TV channel as per statistics. The regime tried to prevent our broadcasting in Egypt, but they did not succeed.”

The TV channel’s official website has more than two million followers, and apparently their audience keeps growing.

“I can show you the messages I receive day and night from people living in Egypt. Messages of frustration. We are expecting something will happen there. This regime can not survive if it continues to show the same behaviour,” Zawba says.

The quest for brotherhood

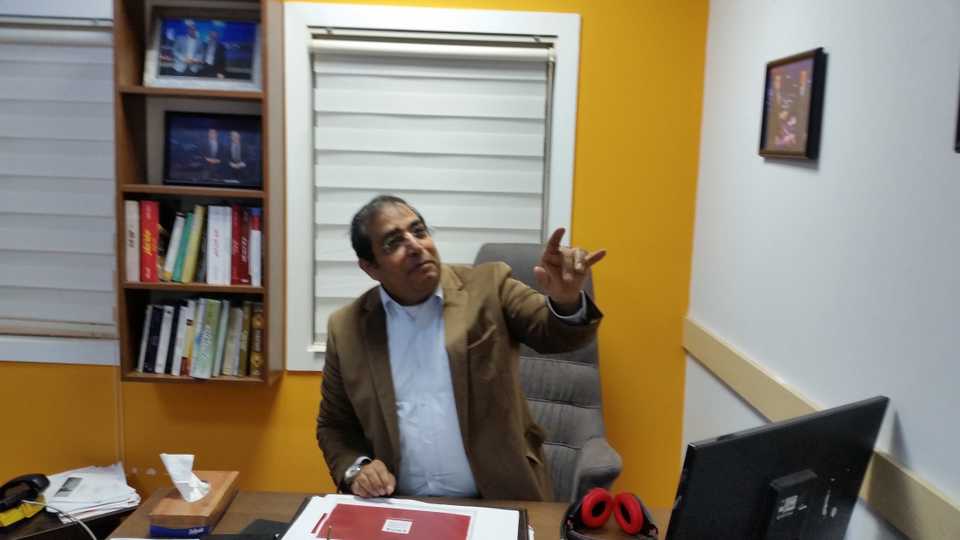

Islam Akl, a former manager of Egypt’s Watan TV, is another veteran journalist who was forced to live in exile after the 2013 military coup. His new talk show, Waseet al Balad, which means downtown in Arabic, will be launched on the Watan TV next month.

In 2015, Akl and his colleagues launched the Watan TV in Istanbul. The channel is funded by Egyptian businessmen who have close ties with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Apart from Watan TV and Mekameleen, there are 13 other Arab-language TV channels operating from Turkey, according to Akl. The Watan’s Facebook page had a large following of 3.5 million people until it was closed down in the last week of March 2018.

Two days after Facebook blocked Watan TV’s official page, they opened a new page, which instantly attracted nearly 300,000 followers. They also have 109,000 followers on Twitter and 99,000 followers on YouTube.

They are apparently growing very fast on all social media platforms. Turkish TV series, which have been broadcasted in Arabic on the Watan, also help them a lot. One of the hits is Ertugrul-Dirilis (Resurrection), Akl says.

Akl’s father was deported from UAE in 1994 on the grounds of being a member of the Brotherhood. The family returned to their native country, Egypt. By 2004, Akl graduated with a law degree from Cairo’s Al Azhar University.

Instead of a career in law, he became a journalist. He thought journalism was adventurous as it involved investigative reporting. Meanwhile, his father became a parliamentarian in 2005 when the Brotherhood foothold was increasing in the Egyptian parliament.

Akl was at Rabaa Square, covering the anti-coup protests. He was shot and wounded by Sisi’s security forces. He was hospitalised and asked to leave the country.

Two decades later, the situation again forced him to leave his country. Six days after the Rabaa massacre, he left Egypt.

He moved to Beirut, where he worked for the launch of a new TV station, Ahrar 25. He could not stay there for long as one of his colleagues, Mosaad al Barbry, was arrested by the Lebanese police. Later on, they learned that one of the ministers from Saad Hariri’s party, who has ties with the Saudi Kingdom, was behind Barbry’s arrest. Saudi-backed Salafist movements supported the coup in Egypt and their opposition to the Brotherhood has been vocal, so the arrest made sense.

Barbry was handed over to Sisi’s army and an Egyptian court sentenced him to life imprisonment. Soon after his release four months ago, he moved to Turkey. He is now leading Watan TV in Istanbul.

After witnessing Barbry’s arrest in Lebanon, Akl went to Sudan and stayed there for two months. By mid 2014, he moved to Turkey where the 37-year-old journalist’s life became relatively stable.

His unflinching faith in ejecting Sisi from Egypt’s power corridors hasn’t faded in exile. In fact, he sounds more stern. “We will keep going after Sisi,” Akl says at his highly secured TV office in Istanbul’s Yenibosna neighbourhood.

Akl says he’s being watched over by Sisi’s spies. “Some people come over here telling us that they were oppressed by the regime. But we aren’t sure about their motives because we could not ascertain their identities,” Akl says.

In the talk show, he says he will highlight the corruption in Sisi’s regime, deploying sarcasm. He strives to instill hope among Egyptians that they can remove Sisi through peaceful means.

“Our struggle will continue without any interruption,” he says, his demeanour calm and composed.

Zaher Al Ghazzawi contributed to this article.

Discussion about this post