On Sultanahmet’s Divanyolu Street, restaurants line the road enticing hungry tourists and locals alike.

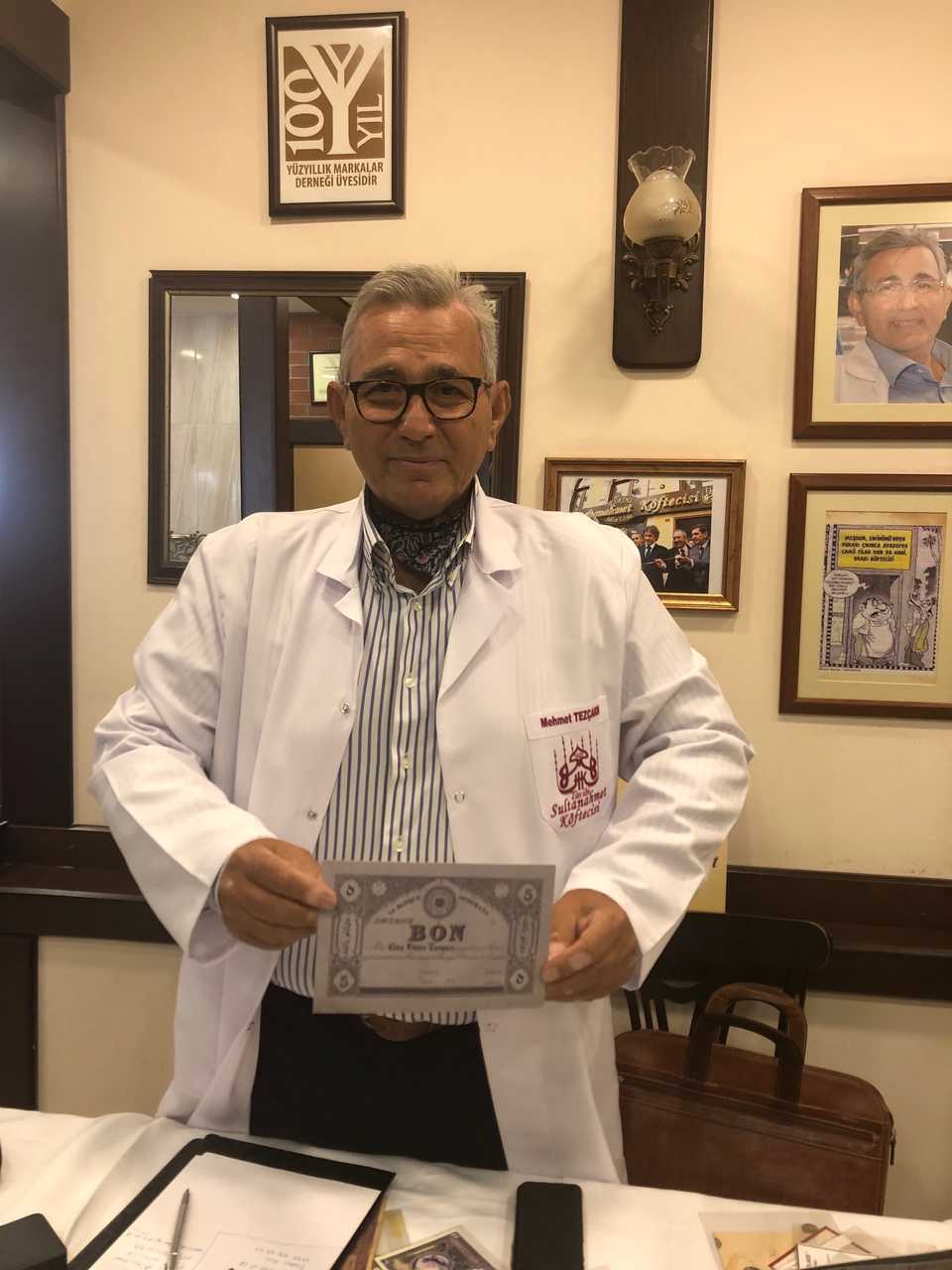

Mehmet S. Tezcakin is the third generation owner of one of these establishments, called Tarihi Sultanahmet Koftecisi ”Selim Usta”, which is located at number 12, a hole-in-the-wall that specialises in and is renowned for serving kofte (meatballs) all day.

The restaurant, established in 1920, is currently run by Tezcakin’s three sons, who have taken over the family business as the fourth generation.

Climbing up the narrow steps of the restaurant, past the sizzle of the kofte on the grill, the smell of cooking wafts by, as bustling waiters in white shirts rush to the customers.

On the mezzanine you encounter a register, above which hangs the sign “cash only/no credit cards”. Climb up another floor, and Mehmet Tezcakin and his wife are there, along with samples from his collection and a copy of his book.

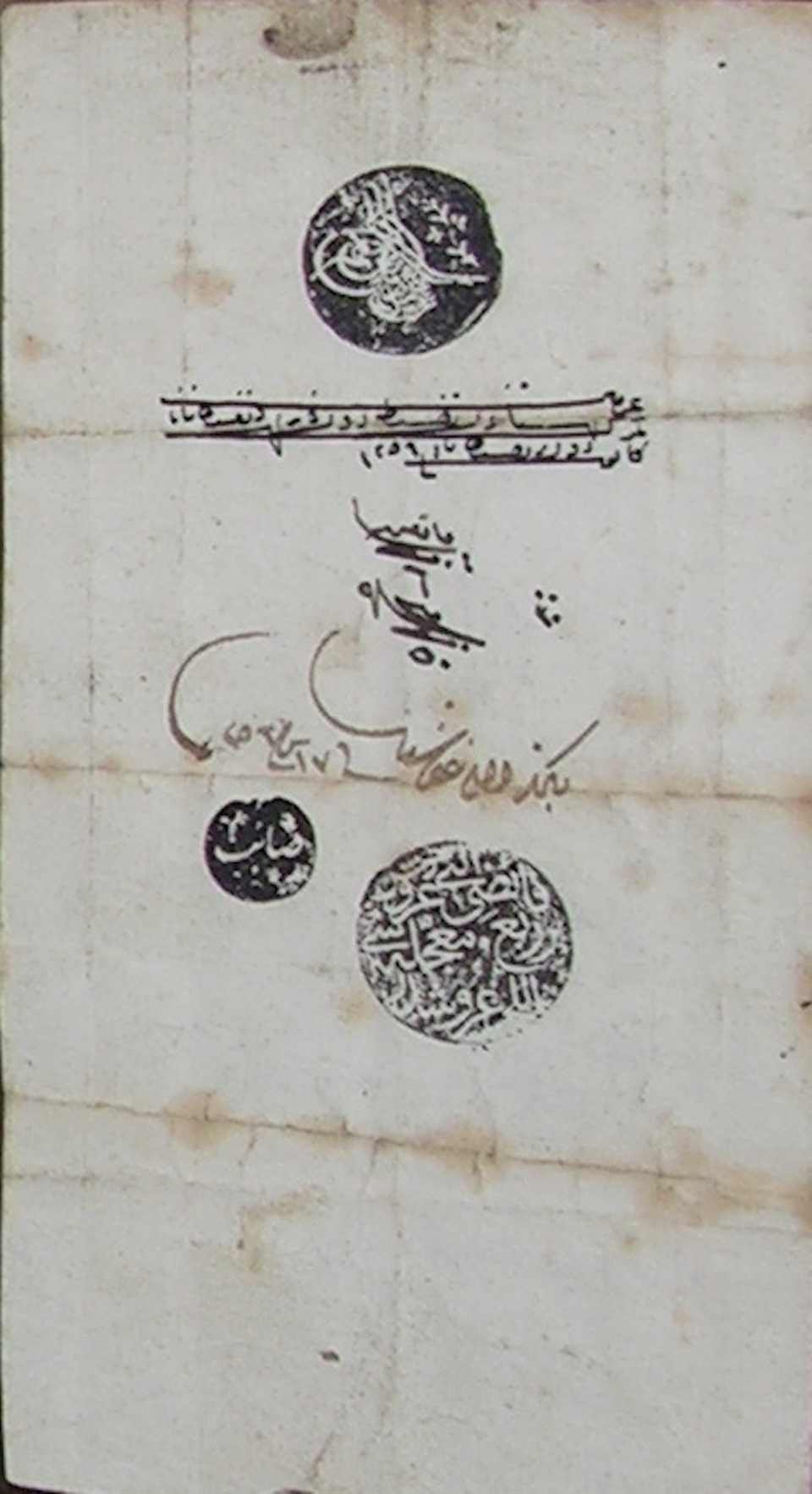

Tezcakin has an interest in cash, except his interest and area of expertise go back decades into Ottoman history. He is a collector of Ottoman bills (and some coins), which, he says, took a lifetime to gather.

He wants his collection to go to a good home, he says, quoting the saying “Adam mezara, mal mezata” that translates as “a man to his grave, and his earthly goods to the auction house”.

Mehmet Tezcakin is a cancer patient, having battled the illness twice already, and gone through a laryngectomy which doesn’t seem to have stopped him from trying to communicate the urgency of his plea. He wears a bandanna on his neck, covering up the operation scars, and whispers with a quiet rasp. His wife Isabella Tezcakin, who has been married to him for 43 years, graciously helps with the conversation.

Tezcakin’s main collection consists of 400 pieces. “I bought 46 lots [at auction] to put together this collection,” he says. “I have collected samples of all Ottoman paper currency. Out of 7,500 pieces, I ended up with 400 in my main collection.”

Tezcakin has been a collector for 50 years, and for 40 years he has been collecting Ottoman currency. He has amassed thousands of pieces which, he says, charts the rise and fall of Ottoman economy towards the end of the empire. He has also published a reference book on Ottoman banknotes essential to the serious collector of such currency.

“Putting together this collection has taught me all the financial movements of the Ottoman Empire during its decline,” he says. The earliest piece in his main [Ottoman] collection dates back to 1839-1840, he notes, while the newest piece dates back to 1922, just before the Turkish Republic was established in 1923.

Tezcakin also has currency issued during the Republican Era. Some of the currency bear the Turkish Republic’s founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s visage or other rural scenes, along with Turkish spelled in Arabic script, from before the official script of Turkey got changed to the Latin alphabet.

Tezcakin says his dream is to see the establishment of a Currency History Museum in Turkey before he dies. To that effect, he has written to Presidential Spokesperson Ibrahim Kalin who has talked about Turkey’s Presidential Library in the press.

Tezcakin tells TRT World that he is ready to donate about 3,000 numismatic books, catalogues and magazines to the Presidential Library. Tezcakin also says that he additionally wants to donate about 1,000 Ottoman kaime (paper money issued by the Ottoman Empire that sometimes acted as bonds), coins from the Ottoman and Republic eras, and his archival materials to be put on display somewhere within the library.

Tezcakin says the biggest problem researchers face is a lack of resource material, and that should the Presidential Library accept his donation, it would “become the most important centre in numismatic history.”

“I watch the disappearance of Ottoman financial history in pain. It is very important that our national memory be preserved for the youth, for researchers,” he adds.

Discussion about this post