“The first floor of Yapi Kredi Kultur Sanat [Yapi Kredi Cultural Activities Art and Publishing Inc] building is mostly set aside for exhibitions from the bank’s collection,” says Tulay Gungen, Yapi Kredi Kultur Sanat General Manager. “We were in the midst of the Sagalassos exhibition when the pandemic hit,” she reminisces.

“We experienced many things during the pandemic regarding viewing,” she continues. “We couldn’t go to the theatre to watch a film, but we watched from television and various screens at home.”

“Karagoz is another type of viewing,” she says. “And I believe it rubs elbows with the pandemic that way,” she puns. “Our exhibition will be open until the end of February.”

Karagoz, My Dear is on display at Yapi Kredi Museum in Istanbul’s Beyoglu district, in the Galatasaray neighbourhood. The exhibition will remain open until February 21, 2021.

“Yapi Kredi is trying to keep our emotions alive, our hearts full of love, and continues with art shows,” she smiles, her eyes crinkling behind her mask.

Director of Yapi Kredi Vedat Nedim Tor Museum, Nihat Tekdemir, says that all precautions have been taken against the pandemic, with a maximum of 10 visitors allowed in the galleries at any given time.

“As Yapi Kredi Kultur Sanat, we may be one of the most important institutions experiencing how difficult it is to stage an exhibition during the pandemic,” he says.

In the book Karagozum, Iki Gozum (Karagoz, My Dear) published in conjunction with the exhibition, Aziz Murat Aslan’s article on Ragip Tugtekin, “an old master,” quotes Alberto Manguel’s collection of essays, Fabulous Monsters.

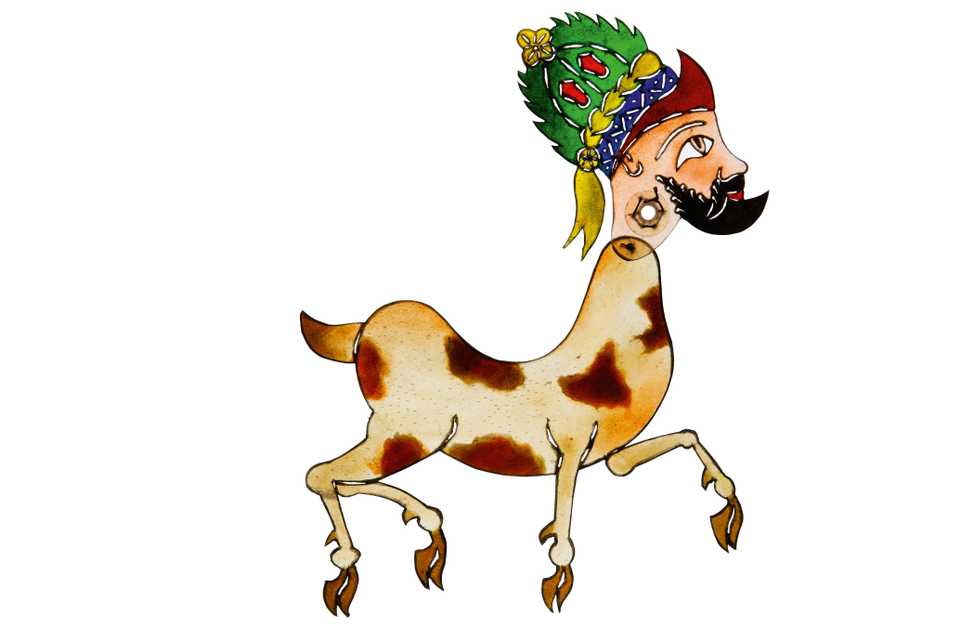

According to Manguel, the duo Karagoz and Hacivat are the Turkish version of Punch and Judy. Aslan writes: “Despite the fact that Karagoz and Hacivat stand at opposite ends of the social scale, they are also integral parts of one body so to speak. Karagoz is illiterate like [Don Quixote’s companion] Sancho Panza, he is a man of the people, humorous and expresses his opinions very directly.

Hacivat, on the other hand, is sophisticated, prudent and well mannered. According to Manguel, Hacivat who constantly recites Ottoman and classical poetry, attempts in vain to civilise Karagoz just like Don Quixote did with Sancho Panza.”

“Our master, Ragip Tugtekin, whose works you see here from the Yapi Kredi collection, was a very valuable teacher,” curator Cengiz Ozek says. “His handiwork is in many collections around the world, but the collection you see here has a special significance: it is work from late in his life, from his real master period.”

“We chose to present the Karagoz figures in a darkened room. So step in, and try to imagine the shadow plays these puppets performed,” Ozek invites the small crowd in. “We would like you to see the attention to detail, the colours of master Tugtekin. The works really affect me. Hope they have the same effect on you, too,” he continues.

He points to the dyes and tools used to make Karagoz figures, as well as the raw camel skin as the canvas on which figures were painted and cut. There is also a Karagoz figure that can be played with against a dimly lit curtain, as if the museumgoer were the puppeteer.

“There are many elements that affect Karagoz’s colourful world. There are the monsters, for example. They point to a relation between Shamanism and Karagoz, I believe,” Ozek says. “Witches, djinns, devils, cursed figures, transformed figures, are all on this wall,” he points to a glass wall overlooking the Yapi Kredi bookstore on the street level below.

“One of the main features feeding Karagoz shadow puppets is folk tales, folk legends,” he enthuses. “Mermaids, dragons with seven heads, creatures from Islamic mythology such as Burak, the Vaq Vaq Tree…”

Ozek points at a map on the opposite wall displaying the many geographies that Karagoz and its variants are performed. “Greece, both [the Greek and the Turkish] sides of Cyprus, Turkey, Syria – definitely before the war– perhaps still, and from time to time Tunisia and Lebanon.”

Tacettin Diker, he was a famous puppeteer who died a few years back, Ozek says. This is one I myself have staged, he adds. He points to Ragip Tugtekin’s figures ahead, from the bank’s collection, and Tugtekin’s influences yet further ahead.

Asked how new characters get introduced to the cast of Karagoz characters, Ozek says “to give an example from myself, my ‘Trash Monster’ was a result of ecological pollution. If there hadn’t been ecological pollution, this character probably would never have existed.”

Ozek takes the small crowd through the shadow play figures, explaining their dress changes through the ages that they reflect. “They reflected the fashion of their times,” he says.

“The end of the exhibition shows examples of other world cultures with shadow play in their repertoire,” Ozek notes. “Next to my Memluk reproductions, you will see an 18th century Chinese shadow puppet, shown along with modern Chinese shadow puppets. Then there are puppets from Indonesia, Thailand, India and Cambodia.”

The museum offers a fascinating view of the world of shadow puppets, and the accompanying book in Turkish and English, resplendent with reproductions of the shadow puppets, is offered for purchase as well.

Discussion about this post