When the coronavirus outbreak erupted in Turkey, the Istanbul Research Institute became one of the leading institutes that went digital with its exhibitions. During self-isolation, which is a hard period for all of us, art lovers can pass time with these digital exhibitions. Here are two digital presentations by the Istanbul Research Institute with which you can explore various details about magnificent Istanbul from the comfort of your home.

The Şişli Mosque

The exhibition “An Ottoman Building in the Early Republican Era: The Şişli Mosque,” created with a selection compiled from the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation’s Photography Collection by the institute, introduces the first monumental religious structure of Republican-era Istanbul with photographs and texts. The exhibition mainly features photographs taken during the construction process of the mosque from 1945-1949, including its courtyard, outbuilding units, fountains, dome and inauguration.

Located on the corner where Halaskargazi and Abide-i Hürriyet avenues intersect in Istanbul’s Şişli district, the mosque was designed by Vasfi Egeli, who once worked as the chief architect of the foundations. Egeli is considered one of the last representatives of the first national architecture style that combines late Ottoman and early Republican periods. It is clear, however, that Egeli employed a different style than his predecessors by creating buildings that differ from traditional examples and using elements from Seljuk and Ottoman motifs. He remained much more faithful to the Ottoman legacy in his spatial design and use of details.

As Beyoğlu began losing ground as a coveted residential area in the 1940s, the elite crowd moved to Şişli. The Muslim population of this cosmopolitan district then needed a mosque. Thus, construction began in June 1945 and was completed in 1949.

The Şişli Mosque reflects classical Ottoman architecture. Considered a stylistic example, it has served as a prototype for thousands of other neo-Ottoman mosques. It is also the first that was built not with the contributions of the sultan or statesmen but through the collective effort of Muslim and non-Muslim populations.

Turkish architect Seyfi Arkan once said: “Since last year, citizens have been donating money and materials so that the Şişli Mosque will rise rapidly. During the weekends, tradesmen, engineers, architects, doctors and people from other professions want to volunteer their work for the mosque, even if it is carrying a stone like a workman. It is especially exciting to see among them Armenian, Greek and Jewish citizens ready to make material and spiritual contributions.”

Therefore, the Şişli Mosque also comes to the forefront as a symbol of solidarity.

Four-legged municipality

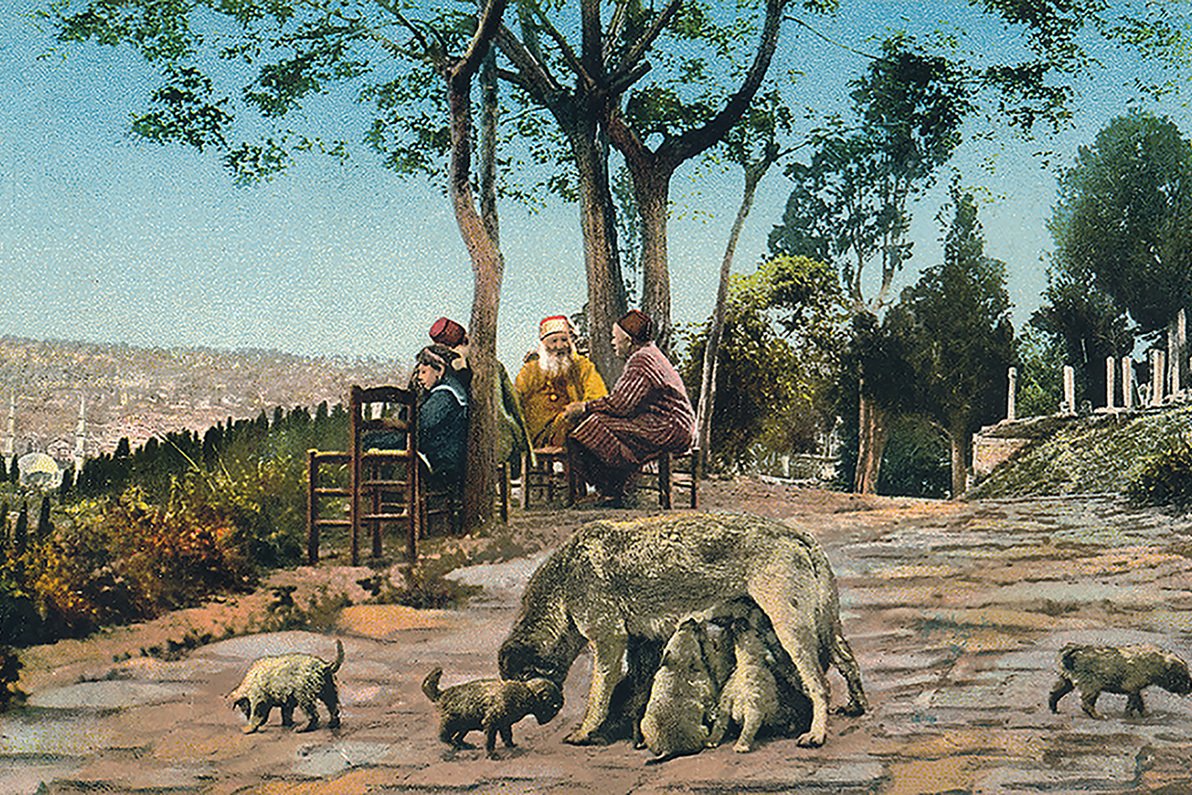

The other exhibition by the Istanbul Research Institute that you can explore from your home is “The Four-Legged Municipality: Street Dogs of Istanbul.” As a presentation shedding light on street dogs, the show reveals that dogs have been an integral part of Istanbul’s daily life in almost all periods. They were the witnesses of political, religious and sociological cultural changes.

The digital exhibit follows the history of these fellow Istanbulite dogs with photos, travel journals, magazines and engravings from the 19th century to the early 20th century.

The project’s adviser, Catherine Pinguet, commented: “Why should there be so much care and consideration for an animal, some might ask. That is the never-ending reproach directed at those who take the animal issue seriously, a commonplace question that friends and protectors of the street dogs in Istanbul know only too well.” She replies to this by quoting Romain Gary’s novel “Les Racines du ciel” (“The Roots of Heaven”), “Because their freedom is the guarantee of mine.”

In the heart of Istanbul, dogs were much loved as they shared their lives with humans from the conquest to the Tanzimat period. They were like residents of a neighborhood. Dogs also assumed duties in the municipality and in the police force. They protected locals against foreigners. This was the golden age for Istanbul’s dogs.

Dark days of dogs

The exile process, however, started for these animals the following period. Possibly because of negative comments from European visitors, Ottoman rulers began to see the dogs as an embarrassment and a threat to public safety. Since it was a period of modernization, serious attempts were taken for dog cleansing.

Even French scientist Paul Remlinger offered a brutal analysis. According to him, the value of a dog with its skin, hair, bones, fat and muscles was between 3 and 4 francs. At the time, there were maybe 80, 000 dogs in the city. His proposal was to open slaughterhouses to process dogs. The government did no such thing but that was not the end as the dogs were sent to Sivriada, a tiny island in the Marmara Sea. To learn more about the fate of the street dogs, visit the exhibition via Google Arts & Culture.

Last Updated on Apr 16, 2020 4:47 pm

Discussion about this post