The coronavirus has affected so many things in our lives, and its influence in art cannot be disregarded either. It is inevitable that many artists confined to their homes are currently creating works that deal with this issue directly, or that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will be reflected in their future works indirectly.

We happen to see many historical and famous paintings, their slightly altered or quote-attached versions at least, shared in abundance on social media for both humor and awareness. These comical works are spreading rapidly. There’s the “Mona Lisa” wearing a mask or Jesus Christ eating alone and having a video chat with his apostles during the Last Supper. We see many other famous paintings becoming subjects of memes on digital platforms nowadays.

Street artists are also creating many expressive works. Artwork expressing support for those fighting the virus, particularly health care workers, have come to decorate the streets. Exhibitions on the coronavirus will also be of interest in the days when the impact of the outbreak declines and curfews finally end.

Throughout history, outbreaks have always been reflected in art and paintings in particular. Artists have created various compositions according to the form of the disease and its impact on society. The plague, which was one of the most common pandemic diseases in the world until the 20th century, had shaped European art.

The Black Death

The plague is a rodent disease carried by flea bites. It is one of the most notorious epidemics that has occurred at different times throughout human history. We find the earliest records of the plague in the Old Testament and Homer’s “Iliad.”

During the sixth and seventh centuries, the plague of Justinian was the first known major epidemic. According to historical sources, it took place in 541, causing great loss of life in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Historians of that period narrate that the total death toll in Constantinople alone reached 300,000 between 541 and 544.

The most destructive form of the plague occurred in Europe in the 14th century. The epidemic caused major losses and accompanied radical changes in medieval history. Due to a lack of resources, the exact death rate cannot be provided, but today’s researchers claim that Europe’s population declined by 45% to 60% back then.

Records about the pandemic, dubbed the Black Death, indicate that it came to Crimea from East Asia by means of the Mongols and that the merchants there carried it to Europe by sea. After all, in the old world, many diseases were carried through ships and animals. The carrier of the plague were ship rats, also known as rattus rattus.

In the 14th century, Giovanni Boccaccio was a living witness to the Black Death. In his book “Decameron,” he describes the high mortality rates and how they are a catalyst for many sociocultural changes. He depicts the extent of the outbreak as follows:

“The plight of the lower and most of the middle classes was even more pitiful to behold. Most of them remained in their houses, either through poverty or in hopes of safety, and fell sick by thousands. Since they received no care and attention, almost all of them died. Many ended their lives in the streets both at night and during the day, and many others who died in their houses were only known to be dead because the neighbors smelled their decaying bodies. Dead bodies filled every corner. Most of them were treated in the same manner by the survivors, who were more concerned to get rid of their rotting bodies than moved by charity towards the dead. With the aid of porters, if they could get them, they carried the bodies out of the houses and laid them at the door; where every morning quantities of the dead might be seen.”

Divine retribution

The Black Death led to radical changes in the economic, political and cultural life of medieval Europe. It also greatly affected the church. Priests were responsible for the burial of the bodies of plague victims, and this class was among the most affected in the social hierarchy. The decrease in the number of clergymen resulted in the recruitment of illiterate priests, leading to a change in the quality of the church’s administration.

From the sixth century onwards, the plague prevailed in much of Europe, creating a dark atmosphere filled with death. Artists of the time also produced their works embroiled in the psychology of such destruction.

Since medical practices against the Black Death were unknown in the 14th century, people sought treatment from saints and priests. Diseases and death were considered divine retribution for sins. Its reflection in art was also based on these religious interpretations. A manuscript illustration dating back to 1424 depicts arrows symbolizing the plague being thrown at the victims by Christ.

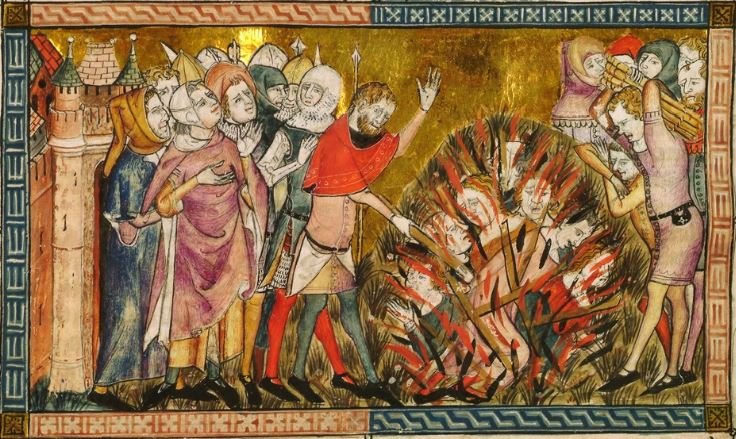

In the chaotic environment depicted by Bocaccio, there were also Christian groups who considered Jews to be the cause of the disease. According to them, the Jews allegedly poisoned the waters and spread the disease. As they did not believe in Jesus, they caused the wrath of God. Over time, the tension escalated, and the Jews captured were put on stakes.

The first of these massacres took place in France in 1348 and later spread to Europe. Pictures that went down in art history as Jewish massacres were painted in the 14th century. The following illustration depicts one of these dramatic events:

Dancing with death

However, the killing of Jews did not stop the spread of the disease. Death then became a widespread phenomenon in Europe. This was addressed in many works of art.

Works called “Danse Macabre” or the “Dance of Death” began to appear. In these paintings, death was personified as skeletons dancing arm-in-arm with humans. The idea that one day everyone would participate in this dance regardless of race, gender or social class was featured in these paintings. All the people, regardless of whether they were male or female, rich or poor, noble or peasants, even the emperor, would be asked to dance by death himself.

Medieval artists always brought up the theme of death in their works, emphasizing the fine line between life and death in hospitals, cemeteries and chapels.

Again, as a result of the plague years, “The Triumph of Death” movement commenced in the art world. Named after the “Triumph of Fame” by Italian poet Petrarca, this movement spread over time across the whole of Europe.

The most striking work was produced by Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel in the 16th century. This painting depicted the whole impact of the plague in Europe. The plague was also depicted as chaos through metaphors such as an unhealed wound, a hungry dog, horsemen, a swallowed cloud or death itself in the form of a skeleton, and of course as an invading enemy.

Patron Saint

Saint Sebastian, one of the first martyrs of Christianity, was considered one of the patron saints against the disease in the aftermath of the plague. Although he was killed with an arrow, a link was established between him and the plague – which was reflected in these paintings. The church’s influence on the people along with the plague appears in paintings as the rendering of many patron saint figures.

The idea of death and the plague remained a subject in art for a long time. Even centuries later, this theme would be featured in new works. In addition to saints, other important figures in history are also depicted in paintings with themes of the plague. Napoleon Bonaparte is one of them.

He is pictured visiting his army in Syria in 1799 in a work by Antoine Jean Gros. At the time, there was a plague outbreak in Syria. The French commander is depicted healing a plague victim with a single touch, just like Jesus cured a victim of leprosy in the Biblical story.

Monument of liberation

After the plague disappeared, the survivors built monuments as mementos to celebrate their survival. The most famous of these monuments is the statue of Pestsäule (the Plague Column) in Vienna, Austria. Besides the plague disaster, the column has also been adorned with motifs relating to the Habsburg dynasty and religion since its inception. Its construction was initiated in 1683 by Matthias Rauchmiller and completed in 1693 by Paul Strudel.

When we delve into the history of art, we come across many plague-themed works. We hope that the impact of the coronavirus will not be as tragic as the plague. However, it is obvious that its effects will run deep in countries that have not been able to shake off the disease easily. I do not know if we’ll see new works depicting people dancing with death. How do you think art will be shaped when we leave behind this COVID-19 pandemic? Guess we’ll just have to wait and see.

Last Updated on May 08, 2020 1:18 am

Discussion about this post