Like many Turkish modernists, the creative trajectory of Altan Gürman’s career as an artist begins in the City of Lights – old, gay Paris. The 1960s were a stormy time in the world due to the runaway success of liberalism. But while conservatives assuaged their headaches, intellectuals and visionaries saw their muses dancing in time to the pulse of social change.

Decidedly constructivist in style, steeped in the cut-and-dry definitions of illustration and screen-printing, Gürman devised new techniques to juxtapose natural forms with those conceived by the artifice of men. The earliest of his works curated by Başak Doğa Temür is from 1965, his penultimate year at the School of Fine Arts in Paris.

His series “Statistics” has the inventive vitality of pop and op art mixed together toward a reevaluation of still life. Centered by a mesmerizing acrylic on canvas depicting a potato, Gürman drew from his studies of botanical and agricultural publications. Playing with a visual vocabulary that to contemporary eyes appears outmoded, he refreshed modern art’s identity.

“Sugar Beet” (1965) explores similar contours, also integrating the medium of plastic, which made for a two-dimensional sculpture of an acrylic painting. The chopped physicality of the work commingles with its repetitive lines of color, which ultimately augments the effect of the subject itself with regards to the mundane, objective perception of what looks like a vegetable.

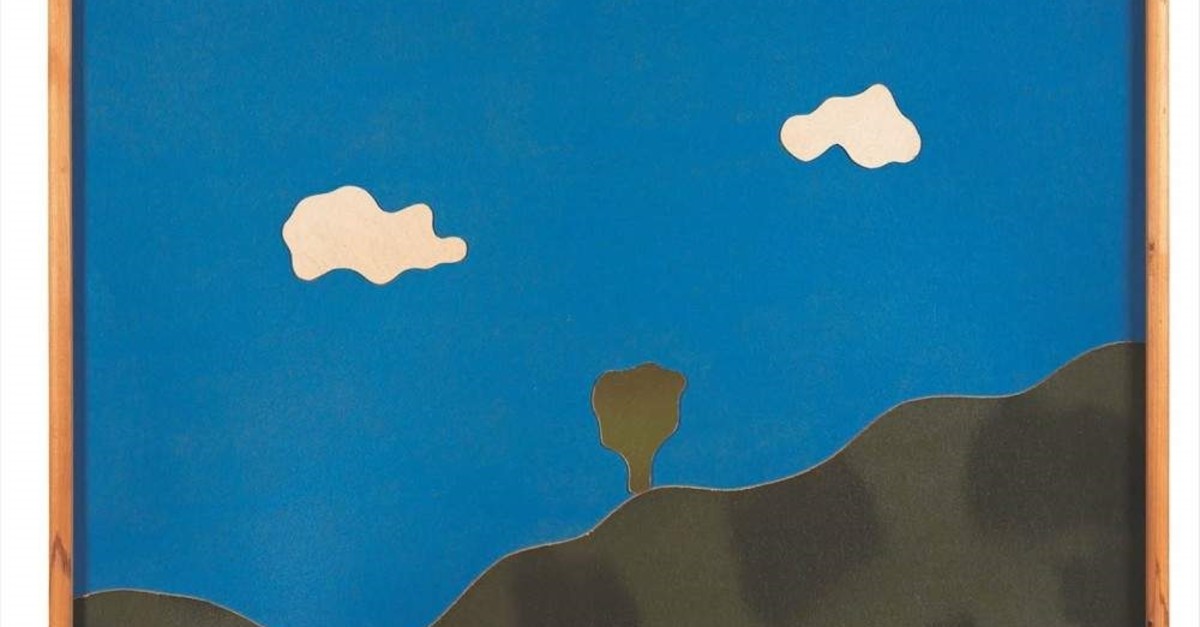

That same year proved utterly productive for Gürman, who, at the ripe age of 30, reflected on his earlier education as a graduate of the Department of Painting at the Istanbul State Academy of Fine Arts in 1960, and sought to diversify his multidisciplinary approach to framed material. The polymers of “Appearance” (1965) shimmer over a green horizon of hills.

The flame and the wick

In 1976, Gürman died, having just entered his forties, but not before creating a distinctive oeuvre that will challenge and redirect the course of art history for as long as it is written. In his final year, he was just establishing himself with his first and only solo exhibition at the Turkish-German Cultural Center.

A pair of linocuts on paper, both untitled, from his “Composition” series in his last year, open the Gürman retrospective at Arter. They evoke the outline of the potato that absorbed his attention in earlier work, only emptied of color in more of a cloud-like depiction. His use of color makes for a diptych of matte browns in contrast with lighter variations.

The red and white stripes aligned diagonally across one of his “Composition” pieces is a common motif also featuring prolifically in his Montage series, also from 1967. The latter works run parallel to those of an American contemporary, Robert Rauschenberg, who merged painting and sculpture to avant-garde, modernistic abandon.

Arguably the most iconic work of Gürman is “Montage 6” (1967), a symmetrical composition that burns into the mind’s eye like an evergreen perennial. Made with cellulose paint on wood, the square backdrop of a cloudy sky is set in contradistinction with a striped red-and-white frame.

The octagonal structure is arguably a subliminal reference to the artist’s underlying dialogue with neoclassicism, the eight-pointed shape being an Ottoman symbol. In her essay for Arter’s exhibition catalog on Gürman, independent curator Duygu Demir draws links between the 20th-century artist and the origins of landscape painting in Turkey.

“The Yıldız paintings are almost ‘screened images,’ in that nature that is mediated through the photograph, which is then mediated further by oil on canvas. Reproductions of mechanical reproductions, they are odd precursors to the structural tactics that would be taken up by Gürman more than half a century later,” wrote Demir.

Perhaps the best examples of Gürman’s artistic quotations of the Yıldız paintings, which were based on photographs of landscaped palace grounds, are from his “Composition” series, enumerated as Nos. 6-9. These works, made in 1967, were curated together by Temür to convey how Gürman modified one consistent idea, varying its colors and shapes in context.

“Composition No. 6” is marked by sharp linearity, its seascape forming an artificial triangle against a camouflage green ground. The multilayered, intentional fakery of paintings conceived in the bygone Yıldız Palace tradition has a surrealistic tone in the hands of Gürman, who returns to naturalism with an eye for the hallucinatory powers of the human mind.

To a land of paint and ink

In Paris and in Istanbul, Gürman’s practice explored an otherworldly military aesthetic. Insightful as a visual commentary on Western, industrial civilization, which is subconsciously and overtly driven by the might of the right, both his “Scheme” and “Montage” series are rife with that signature patchy swirl of greens and browns.

But in the creative progression that spanned his most active 12 years, he is not at all heavy-handed when approaching the graver themes that code military life as separate from the civilian domain, while each retains its uniformities. Nearly invisible, the image of a tank is collaged over cardboard in one of his pieces titled “Scheme” (1965).

In another piece from the “Scheme” series, a photographic print of a man in the garb of a blue-helmeted peacekeeper looks into the imaginative field of the artwork at the raised figure of an aerial bomb. The depth performed by the work of gouache and pencil on cardboard is compelling for its inward direction of focus.

Others are not so subtle. A height of deep green reaches up to a thin layer of blue sky, wherein wisps of cloud are overwhelmed by the unrealistic stretch of terrain in an untitled composition. Next to it, Temür chose to hang “Montage 4” (1967) in which a nearly identical range of colors and forms are blocked by red-and-white boards and strung with barbed wire.

His initial montage work, enumerated as “M1,” is a triptych, painted with cellulose into a cold metal sheet of crosshatched, bolted paneling. The two that followed that series adapt camouflage netting, obscuring their title, seen in yellow lettering, “M2,” and “M3,” at their core. These works, and others, were drawn in the “Notebook” (1965). Its pages were filmed for the show.

Leafing through the artist studies, drafted in Paris, the contents of his psyche are projected in a clear, organized fashion, straight from the SALT archives where much of the artist’s work has been preserved since gaining well-deserved attention following the more alternative currents of contemporary art appreciation in Turkey.

His masterwork is a collage he made in Istanbul with print and cellulose paint on paper. “The Dream of Neo-Classicism” (1975) has the ingenuity of Giorgio de Chirico, but is incomparable in its filmic poise. The figure at the top is also in “Appearance IV” (1973), from Italy, and reappears in the nine-piece sculpture, “Soldier” (1976), which was reinterpreted in 2013.

Discussion about this post