China’s increased power and influence has primarily come through economic means, but the rising power might be forced to change its approach.

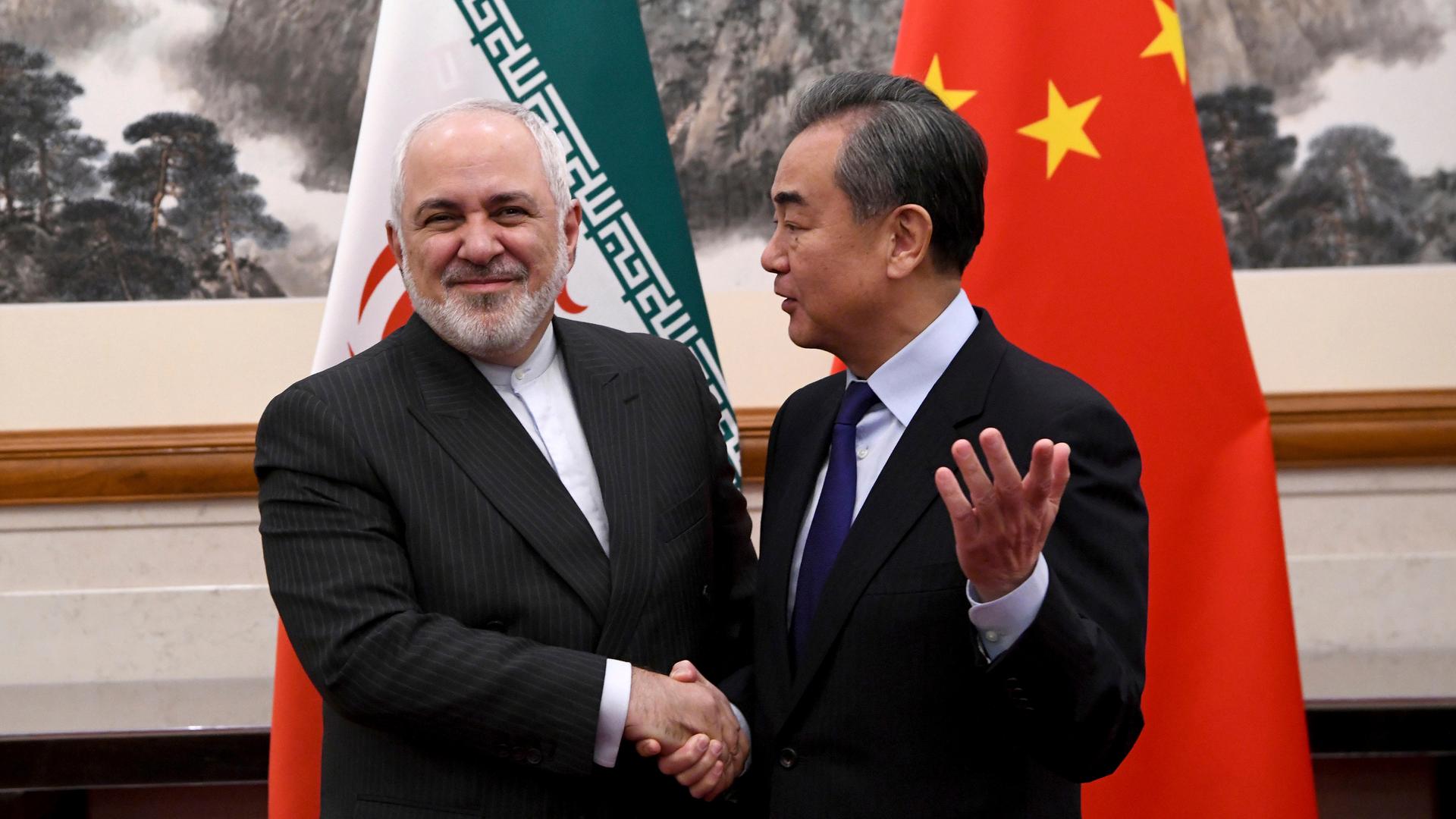

Since the US killed top Iranian general Qassem Soleimani earlier this month, plunging the Middle East into further turmoil, there has been much discussion of the consequences for Iran’s key ally, China. Pundits have opined that Beijing might benefit from the current tensions.

And well, it might.

Countering China is a stated priority of the Trump administration, but chaos in the Middle East would likely distract Washington’s attention from East Asia. The current period would then resemble the aftermath of 9/11 or the global financial crisis in 2008 when China was able to capitalise on American incapacity.

However, spiralling instability in the Middle East poses serious risks for Beijing. China is the world’s number 1 oil importer and receives much of its energy from the region. A conflict would undermine China’s energy security, while also endangering the million or so Chinese expatriates living there.

Moreover, China is the biggest trade partner of numerous Middle Eastern states (including Iran), it has substantial investments in the Gulf, and plans to expand its Belt and Road Initiative there. One of the BRI’s six infrastructure corridors, the China-Central Asia-Western Asia Economic Corridor, transits through the region.

Beijing, therefore, wants stability, above all, to safeguard its economic activities. Fears that China and Russia will stand up for Iran against the US, risking a world war between the superpowers, are absurdly overblown.

Beijing’s response to Soleimani’s killing has been muted, consisting of little more than angry words.

That is partly because the US is far more critical to China than Iran. China might be Iran’s foremost trading partner, but their economic ties pale in comparison to those between China and America. If Beijing stood up for Tehran, it might jeopardise the phase 1 trade deal it is about to finalise with Washington.

Added to that, Beijing will surely not want to undermine its ties to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi by siding firmly with Tehran. Saudi is now China’s top oil supplier, and economic links between China and the Gulf are deep and growing. As Jonathan Fulton writes, “the Gulf Cooperation Council is a far more attractive set of partners than a revisionist Iran.”

When President Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 and reimposed sanctions, some expected China to break the rules and continue its trade with Iran. Not so. While Beijing is still Iran’s top oil importer, imports have slumped, and overall trade has dropped precipitously since sanctions resumed.

So, China is unlikely to deepen its ties with Iran as a result of current tensions. Reports of a vast $400 billion Chinese investment package last year are highly implausible, given the downward trajectory of China-Iran economic ties since Washington pulled out of the JCPOA.

Beijing might exploit the woeful state of US-Iraqi ties to consolidate its foothold in Baghdad. Washington is currently pushing back against Iraq’s decision to expel American troops. While China is unlikely to commit forces of its own, given its reluctance to deploy forces anywhere in the region, economic ties might strengthen further.

It is often assumed that China is desperate to expand its political and military power and waits eagerly for the US to slip up so it can pounce and reap the dividends. This caricature of an expansionist Beijing is reflected in the Trump administration’s allegations of Chinese ‘debt-trap diplomacy’. But it does not pass muster.

China has only recently opened its first overseas military base, in Djibouti. It reportedly has a facility, of sorts, on the Tajik-Afghan border, too. And there are unsubstantiated rumours of further military sites being considered at Gwadar in Pakistan and elsewhere. But Washington has around 800 military bases around the world. Many more than China.

Far from reflecting Beijing’s global expansionism, its military footprint reveals a cautious power that is highly reluctant to match its growing economic activity with a corresponding level of political and security engagement. This is nowhere more obvious than in the Middle East, where Beijing has mostly kept out of regional conflicts, including the fight against ISIS.

True, China’s security presence is expanding slightly. It contributes generous support to UN peacekeeping missions. It is involved in anti-piracy initiatives in the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea, and in 2011 and 2015 conducted large evacuations of its citizens from war-torn Libya and Yemen, respectively.

Furthermore, in December last year, it participated in a joint naval drill with Russia and Iran, the first of its kind. But it would be wrong to see this as evidence of a nascent anti-western security alliance. Shortly beforehand, Beijing conducted a naval exercise with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s nemesis.

Indeed, China has tried to stay out of the region’s disputes, preferring a posture of neutrality. It maintains good ties with Iran, on the one hand, and Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel, on the other. In 2016 President Xi signed comprehensive strategic partnership agreements with Tehran and Riyadh on the same overseas trip, demonstrating impartiality.

Beijing’s approach contrasts sharply with the US practice of forming security alliances, often sealed in defence treaties, which impose binding commitments on both parties. This means that Washington tends to stand firmly behind old allies like Saudi Arabia, even when their policies do not serve American interests.

As Dina Esfandiary and Ariane Tabatai write in Triple Axis: Iran’s Relations with Russia and China, “Beijing, however, approaches its relationship strictly based on its interests. In other words, China adopts a pragmatic approach that is not set in stone and where allies are not necessarily viewed as a long-term investment.”

By maintaining ties with countries on both sides of regional disputes, like Saudi Arabia and Iran, China is well-placed to serve as a mediator and help reduce tensions. The US, by contrast, is far too heavily tilted towards the Gulf states to perform such a role, especially under the Trump administration, which appears hell-bent on destroying the Iranian regime.

Beijing should, therefore, build on its favourable diplomatic situation to play a more active role in regional politics. That China can be a constructive partner was shown by its help negotiating the JCPOA. Eventually, Beijing will also have to consider a security presence in the Gulf to ensure freedom of navigation and protect its energy supplies.

Japan, which imports almost all of its oil from the Middle East, is already deepening its involvement. Prime Minister Abe is using a scheduled trip to the region to deescalate tensions through mediation. He is also planning to deploy Japanese naval forces to the Gulf of Oman. If Tokyo, why not Beijing?

China is understandably reluctant to get more deeply involved in the Middle East. Its hands-off approach has served it well and compares favourably with Washington’s interventionism. Chinese energy supplies have continued to flow, even at times of heightened instability.

China is now the world’s second-largest economy, with interests far and wide. Both for its own sake and the world’s, it must shoulder more of the responsibility for regional security. If the current tensions in the Middle East do benefit China, it will be by forcing Beijing to accept the inevitable and act as a global power.

Author: Rupert Stone

Rupert Stone is an Istanbul-based freelance journalist working on South Asia and the Middle East.

Source

Discussion about this post