The coronavirus has given us a chance to re-examine our excesses, and how we approach faith.

The Covid-19 pandemic has sent millions of people around the world into self-isolation, or quarantine, to protect themselves as well as others who might be more vulnerable to the virus because of advanced age, underlying conditions or weakened immune systems.

Videos on social media from various countries show people in quarantine, doing their best to be spontaneous and inventive in finding activities to do at home.

There are several heartwarming clips of Italians singing opera from their balconies, and Spaniards playing bingo. Time is being made to pass with recreational activities which used to be central to the lives of previous generations. These include old-fashioned parlour games; knitting and embroidery; pickling and slow cooking, as well as the vanishing art of face-to-face conversation (within immediate families of course).

President Macron, in his emergency speech to the French nation on Monday, urged France’s citizens to stay at home, and turn there to the enlightened business of reading books.

But what about the weightier need for spirituality which, increasingly in the last two decades (for political and social reasons) has taken such pressingly-public forms?

What can be done about preserving communal religious practice for those who are invigorated by it, when places of worship have been suspended – some for the first time in their histories?

Jews are being asked to refrain from praying at temple; church and mosque services are being cancelled, with the aim of preventing large gatherings from forming, in the hope of putting brakes on the disease’s virulence.

We are being forced to admit – against every notion that contemporary consumerism has sold us so for decades – just how little agency we actually possess. Our daily lives have changed, perhaps irrevocably so.

Many are saying that this was a long overdue development. The way we were living before Covid-19 hit like a meteor, was damaging to the earth; to other creatures, and to ourselves. Only a force majeure could have thwarted man’s rapid descent into all-out destruction. From this angle, coronavirus may yet prove to be a salutary force – at least for those who manage to survive it.

The restrictive rules on public movement put in place by different governments are modifying the way we live and even the way we worship and pray. Will we have to follow religious services from afar? We definitely have to avoid physical contact or closeness. So instead of attending Friday prayer in mosques; Saturday synagogue services or Sunday Mass, public worship may have to relegate itself to realm of the virtual.

Ironically, in hemming in its communal and political manifestations through a lockdown, religion may become more personal.

Pilgrimage halted

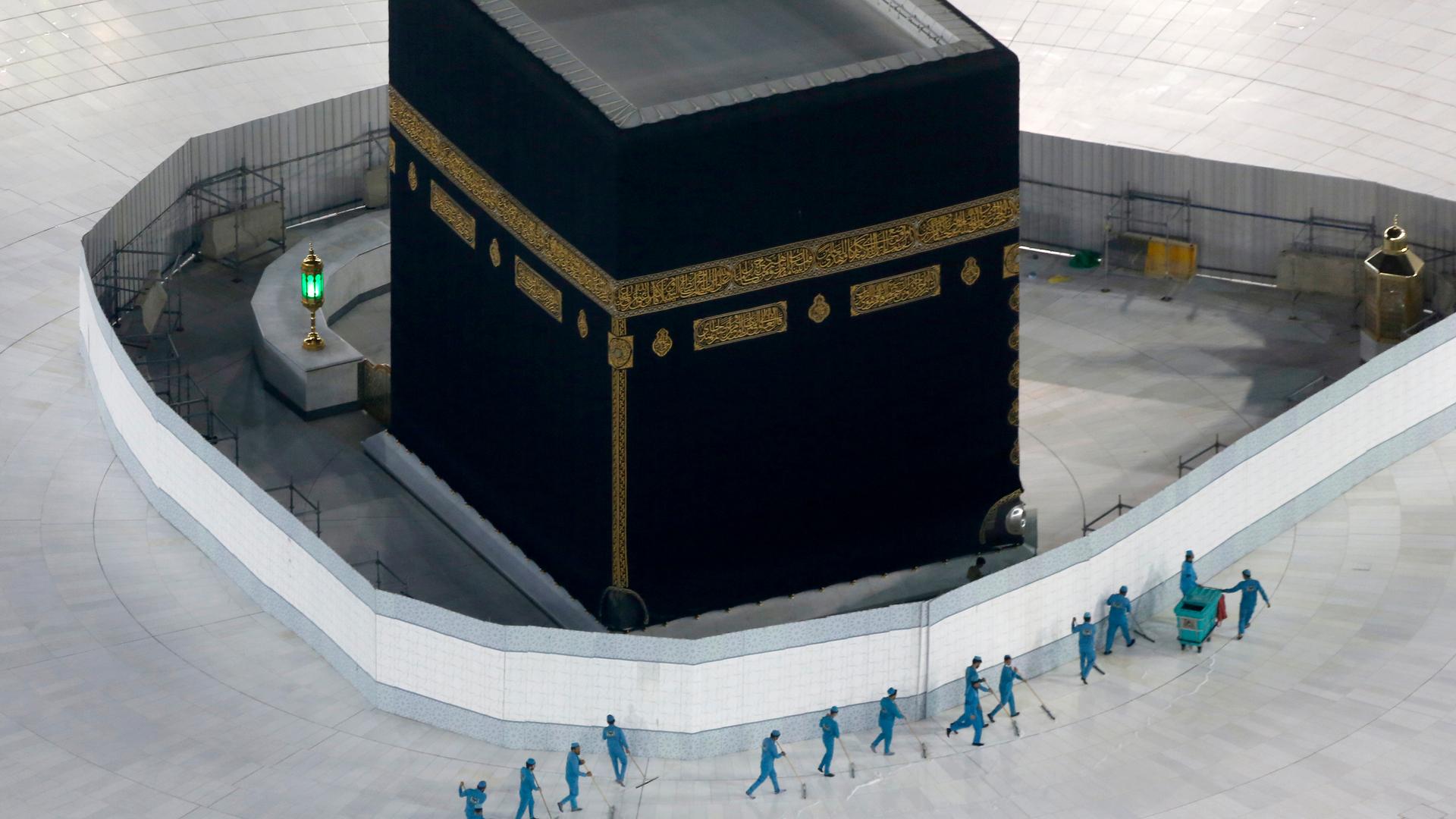

Saudi Arabia has now reopened two of the holiest religious sites in Islam, the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca and the Masjid al Nabawy in Medina, after having shut them for sterilisation. Nevertheless, these sites remain closed to foreign pilgrims from 25 different countries. Even citizens (or residents) of Gulf Cooperation Council countries who wish to enter the Kingdom, now must wait 14 days before they can do so, if they are found to have recently travelled outside the region.

The images of an empty Kaaba have been bewildering to Muslims around the world.

About eight million go on the non-obligatory pilgrimage (or Umrah) every year.

Some of these millions live in France, where local restrictions have been put in place. The French Council of Muslim Faith (CFCM) has given instructions to 5 million Muslims across the nation not to attend Friday prayers at mosques. This is in tandem with the Macron government’s stern warning to people to stay at home. Muslims in France who are used to attending Friday prayer, will now have to worship at home, as will Catholics, as Sunday Mass has been cancelled.

On March 15, in an effort to slow down the spread of the pandemic, dioceses around the world began suspending public celebrations of the Eucharist. Priests in France celebrated it in empty cathedrals and churches – broadcasting the service via Youtube and Facebook Live. Those parishioners who had access to the internet or were in possession of smartphones or computers, could follow.

Intrigued by this new development, I myself watched a celebration of mass on social media, broadcast from a church in the Var that I know very well. The experience of watching virtually, rather than participating physically, was somewhat unsatisfactory. Parishioners around the world are hoping that they will be able to attend church services again soon, though the privations being endured by those of all faiths, may come to open more hearts to God, precisely as the doors of places of worship close.

I believe that the coronavirus pandemic will not jeopardise faith, but refine it. As in Muslim Sufi interpretation, that which is pulled away from the body, becomes closer to the soul.

We may no longer be able to come together physically to pray, but does it matter so much, especially on a temporary basid? The essence of prayer – though it differs with each religion – is an intensely private act, requiring no priestly cast or temple to perform it.

We would do well to reflect on what it means to set faith to work, so as to bring relief and comfort to those around us, who might well feel helpless or lonely during these extraordinary times.

Rather than chafing at having to be confined at home, we might instead think of prisoners who are always confined; or be grateful that we have a roof above our heads at all – a roof that every dispossessed refugee fleeing war and tyranny can only dream of.

The coronavirus and its consequential quarantine may well nudge us finally to comprehend just how precarious and fragile life actually is, and to reflect on freedom, which is so very precious, that millions of people around the world are prepared to give their lives to win it for their children.

Author: Alexander Seale

Alexander Seale is a journalist, as well as a radio and television broadcaster in French and English. He is a specialist in French and European politics and culture. He lives in London, where he trained at the BBC.

Source

Discussion about this post