Islamic calligraphy, an awe-inspiring branch of art that has been preserved for centuries in the hands of great calligraphers, will now be introduced to the world. Turkey’s Culture and Tourism Ministry has prepared an introductory film to raise national and international awareness about Islamic calligraphy, on the path to becoming an intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

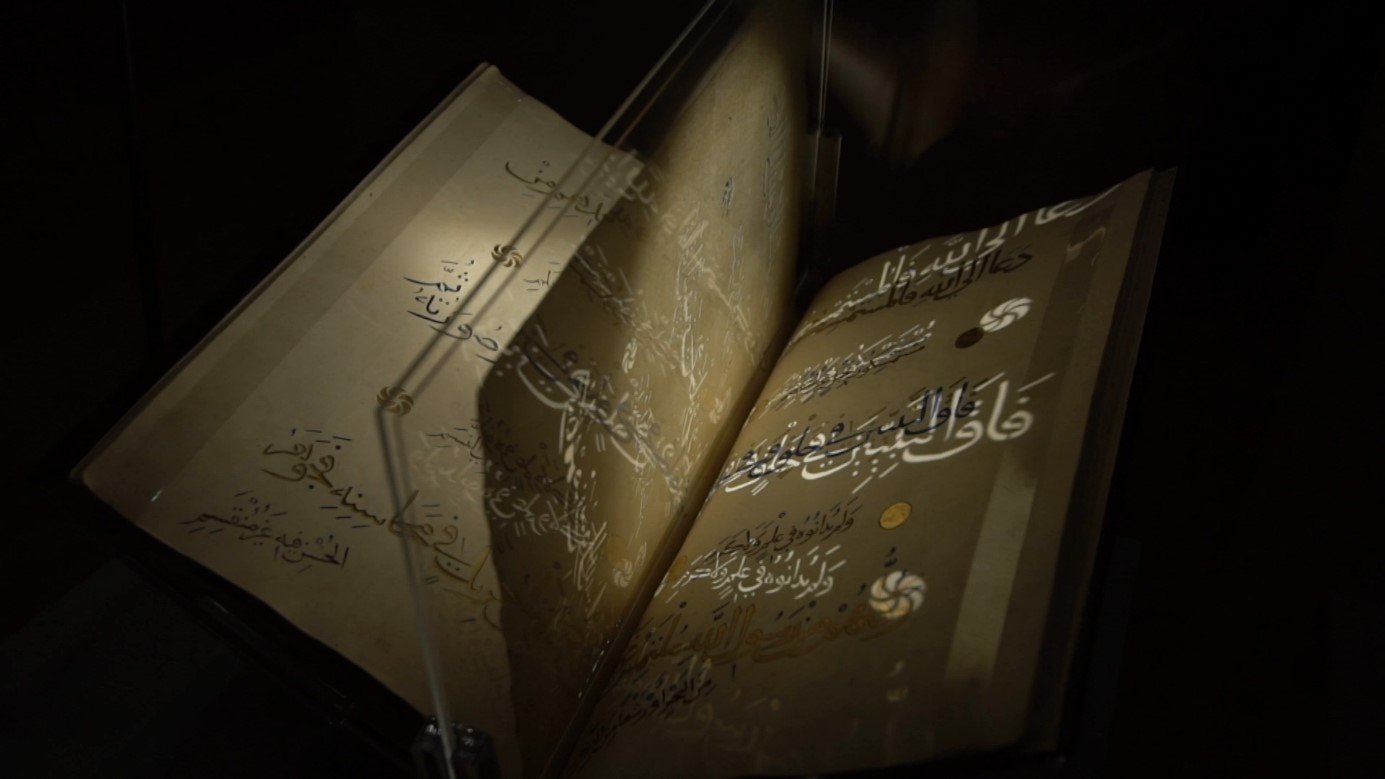

In the film, which includes sights from Çamlıca Mosque and historical sites of Istanbul, there are also images of Holy Quran manuscripts displayed at the National Library’s “Trace of Ink” exhibition, located inside the Presidential Complex in Ankara.

The introductory film showcases the subtleties of Islamic calligraphy over hundreds of years. It is narrated by Turkish classical book artist Uğur Derma, awarded as a Living Human Treasure, and the calligraphers Hasan Çelebi and Fuat Başar.

Prepared in both Turkish and English, the 10-minute film is available in Turkish on the ministry’s website.

Casting light from past to future

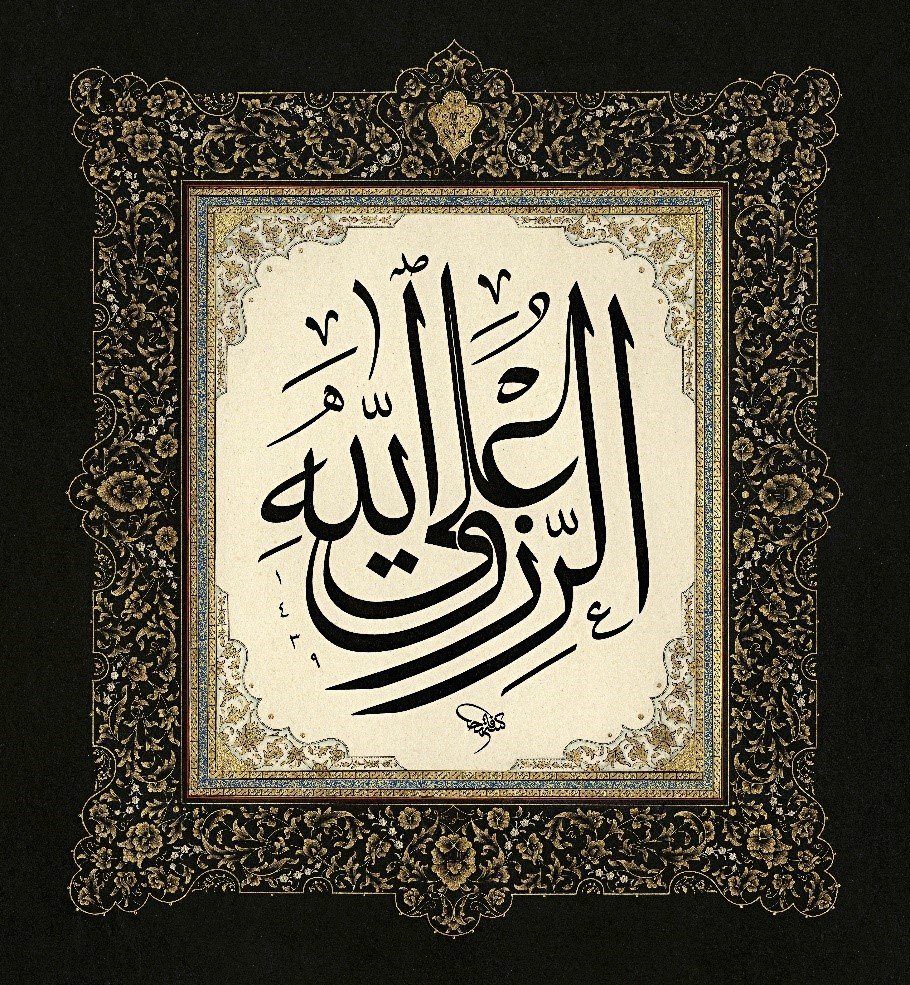

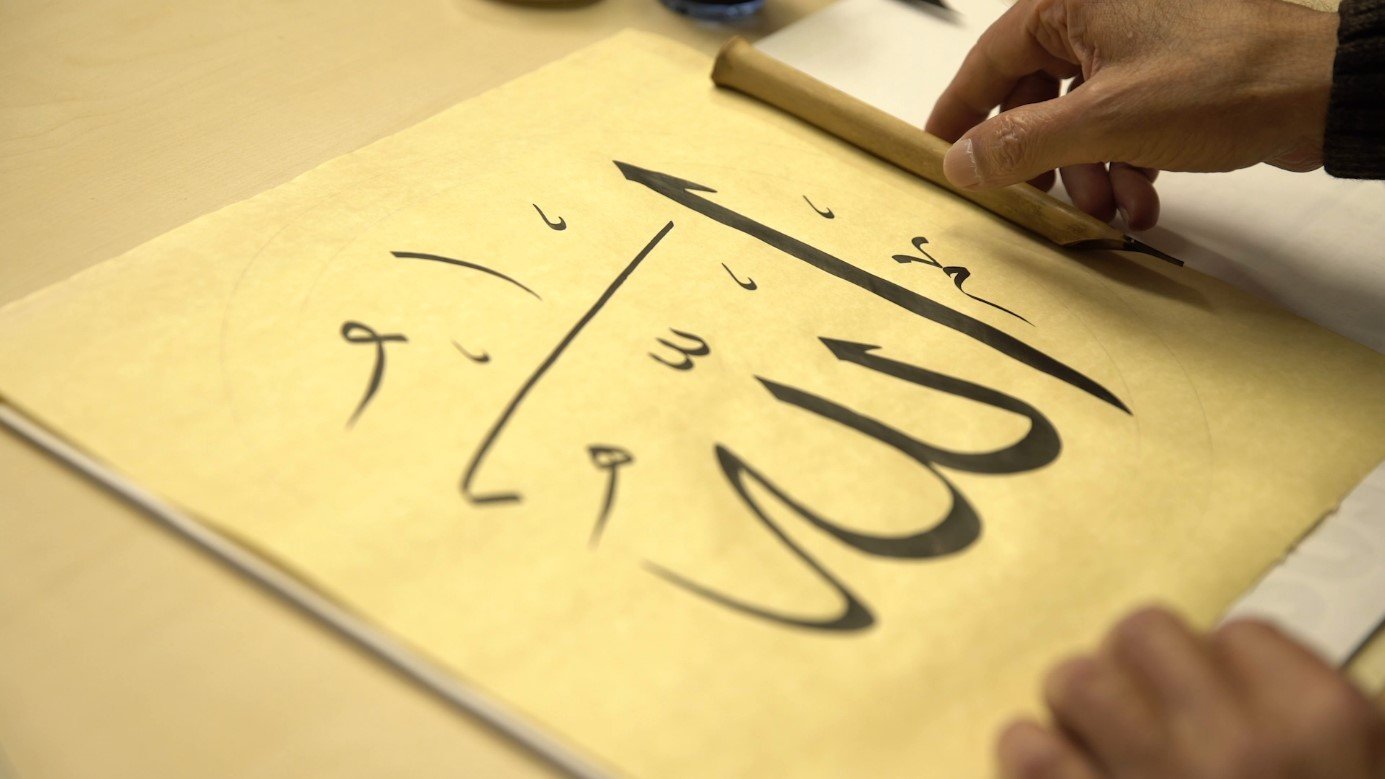

Islamic calligraphy is born out of the effort to write the Quran most beautifully, using the art of writing with a reed pen and soot ink. It takes into consideration aesthetic values and sheds light from the past to the future, both religiously and artistically.

The form of art has been used to adorn Islamic architecture for centuries. It has served as a remarkable decoration tool for doors, walls, mihrabs, minbars and domes, enabling people to read messages given with love.

The art of calligraphy is commonly called “hüsn-i hat” in Turkish. The word “hat,” derives from the Arabic “hatt” infinitive, meaning writing, path, or line. It has been used to describe “the art of writing Arabic script beautifully.”

Calligraphy, first referred to by the Arabic script, became a common value of the Islamic community a few centuries after the Hegira, the migration of the Prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina in 622, and has been classified as Islamic calligraphy. Research on Arabic inscriptions dating back to the centuries before Islam has revealed that the Arabic writing system is a continuation of the adjacent Nebat script, originally linked to the Phoenician script.

The Arabic script, which took various names before and after spreading to Mecca and Medina, started to be referred to as Jazm. Named Medeni (Medinan) in Medina, it was divided into two styles over time. The ones whose vertical letters were long and written from right to left were called Maʾil (slanted) script, and those whose horizontal letters were overextended were called Mashq (from Arabic root word Mashaqa, to extend or stretch). After Prophet Ali made Iraq’s city of Kufa the center, this art made great progress and gained the name of Kufic. After this date, the word Kufic gained a general meaning and was used from the birth of Islam until the Abbasid period.

Kufic was used for 150 years during the Abbasid period. Ibn Muqla, the famous Abbasid vizier and calligrapher from Baghdad, succeeded in developing a system that determines the main dimensions of the article thanks to his geometry knowledge. For the beauty of the letters, he considered dots, circles and alif as a standard measure. Within these measures, he laid out the procedures and principles of six kinds of scripts called Muhaqqaq, Reyhani, Thuluth, Naskhi, Tawqi and Riq’a. All of these were called Aqlama al-Sitta (Six Scripts). These six styles of writing were developed a century later by the hand of Arab calligrapher Ali B. Hilan.

Calligraphy, which later progressed even further on the road to development, became more beautiful with more prominent rules 200 years later with the efforts of Abbasid Caliph Yaqut al-Musta, who died in 1298.

After the Abbasids were erased from the stage of history in 1258, the superiority in writing was taken over by Turkish and Iranian calligraphers. Although the Iranian calligraphers wrote these six styles according to their own understanding, they did not depart from the style introduced by Yaqud. Ottoman Turks, on the other hand, were pioneers in calligraphy.

Some of the pioneers of Turkish calligraphy include Sheikh Hamdullah, Ahmed Karahisari, Hafiz Osman, Mustafa Rakim, Mahmut Celaleddin Efendi and Yesarizade Mustafa İzzet Efendi.

Sheikh Hamdullah, who was regarded as the father of the Ottoman-Turkish calligraphers in the 16th century, brought a never-before-achieved beauty and maturity to these six styles. During the reign of Sheikh Hamdullah, Thuluth and Naskhi spread rapidly due to their proximity to Turkish taste, and only the Naskhi was used in the writing of the Quran. The success of the calligraphers was commemorated by the saying, “he wrote like the sheikh,” since those who were born after Sheikh Hamdullah followed in his footsteps in writing. This situation continued for more than 150 years.

In the second half of the 17th century, Hafiz Osman created a unique calligraphy style by sifting through Sheikh Hamdullah’s style. As Hafız Osman’s groundbreaking era in calligraphy continued with all its majesty, a century later, İsmail Zühdü and his brother Mustafa Rakım created their own accents inspired by Osman’s writings. Mustafa Rakım topped all calligraphy styles with his perfection, especially in Thuluth Jali, as in his writings of Thuluth and Naskhi, and managed to transfer Hafız Osman’s style from Thuluth to Jali. Sami Efendi, who came after Mustafa Rakım, gave a new direction to Mustafa Rakım Efendi’s style by applying the letters of İsmail Zühdü’s Thuluth letters to Jali.

Istanbul became the immortal center of calligraphy after it was conquered by the Turks. This fact, regarded as indisputable in the entire Islamic world, has found its expression most delightfully with a well-known saying, “the Quran was revealed in Mecca, recited in Egypt and written in Istanbul.” The entire Islamic world rushed to Istanbul to learn calligraphy.

4 files for intangible heritage

Turkey, one of the top five countries that have registered the most elements in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists, presented four files to UNESCO this year.

The country applied for the inclusion of four of its cultural values to UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage list, including Tea Culture: Symbol of Identity, Hospitality and Social Interaction, Tradition of Nasreddin Hodja Jokes and Mey/Balaban Wind Instrument Craftsmanship and the Art of Performance. Hüsn-i Hat: Islamic Calligraphy was also delivered to UNESCO last March.

Last Updated on May 13, 2020 3:04 pm by Irem Yaşar

Discussion about this post