Late Ottoman and early Republican thought was greater informed thanks to the contributions made by the Turkish thinkers from mostly Muslim territories under the rule of the Russian Empire. Following the Russian invasion of the Caucasus, Crimea and Central Asia, many Muslim and Turkish (or “Turkic” as preferred by Western authors) populations came under the sovereignty of the Tzars. After the fall of the Giray dynasty of the Crimean Khanate in the late 18th century, Russia continued its policy of territorial expansion in the Caucasus and Central Asia, both of which had vast expanses annexed through the long 19th and early 20th centuries – mostly thanks to the excessive use of firearms, in a way not dissimilar to the way Russia has operated more recently in conflicts with Georgia, Chechnya and Ukraine.

Russian imperialist policies in the aforementioned Muslim territories involved the recruitment of the local elites through the higher education offered by heartland Russia. Moscow universities and technology colleges taught the children of notable Muslim families from various regions to allow for the greater reception of a Russian mentality among their peoples. From the early stages of this imperialist expansion, the Russians relied on their relationship with loyal local elites – in the northern Caucasus, especially. The upbringing of a Russo-Muslim educated elite would help their imperialist policies forever, by fostering to a gradual transformation of non-Russian populations into a common Russian Imperial spirit.

However, not all elites or intellectuals complied with the imperialist fantasies of the Russian invaders. There were frequent rebellions throughout the so-called Russian Empire led by local religious and/or tribal notables running simultaneously with the general awakening of Turkish nationalism among intellectuals, who had been educated by both their local madrasahs and Russian universities or polytechnics. Interestingly, a number of Turkish ex-subjects of imperial Russia helped to institutionalize Turkish nationalism during the Second Constitutional Era. Aside from Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev, the architect of the ideology of Muslim national communism, who was initially expelled from the Bolshevik party and later tortured, imprisoned and executed, non-Bolshevik intellectuals as Yusuf Akçura, Ahmet Ağaoğlu (Agayev) and Ismail Gaspirali (Gasprinsky) made significant contributions from the desk of the Turkish nationalist movement in the late Ottoman and early Republican eras.

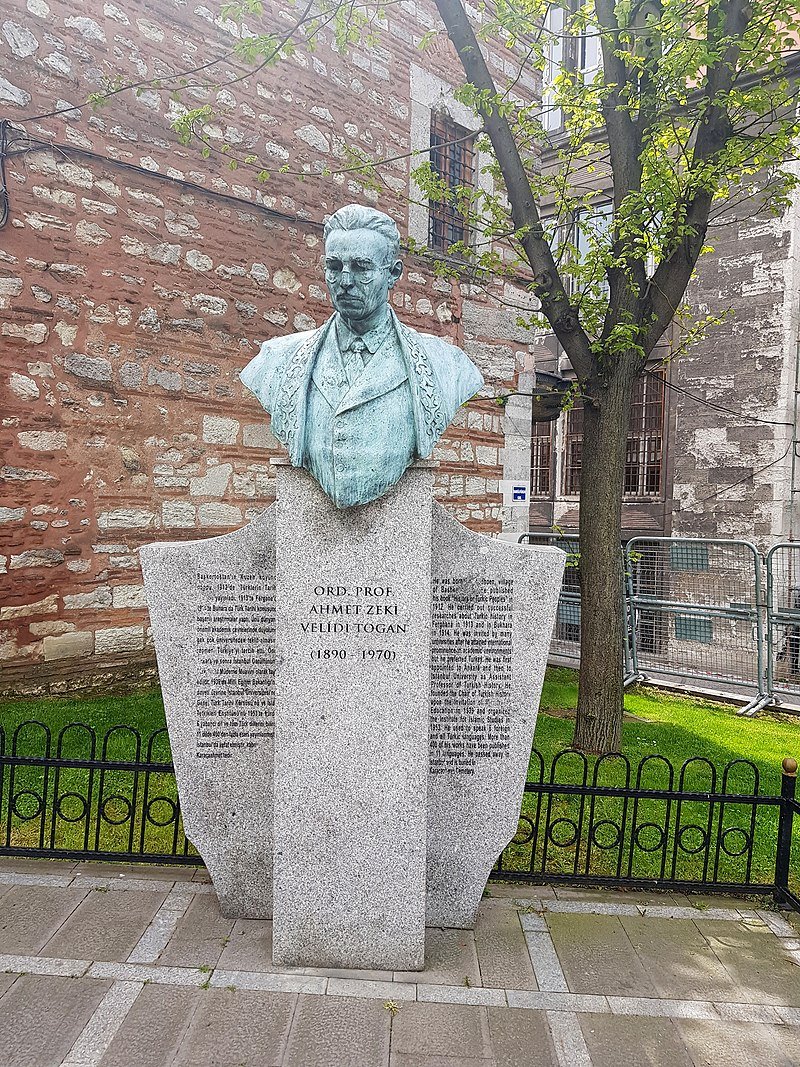

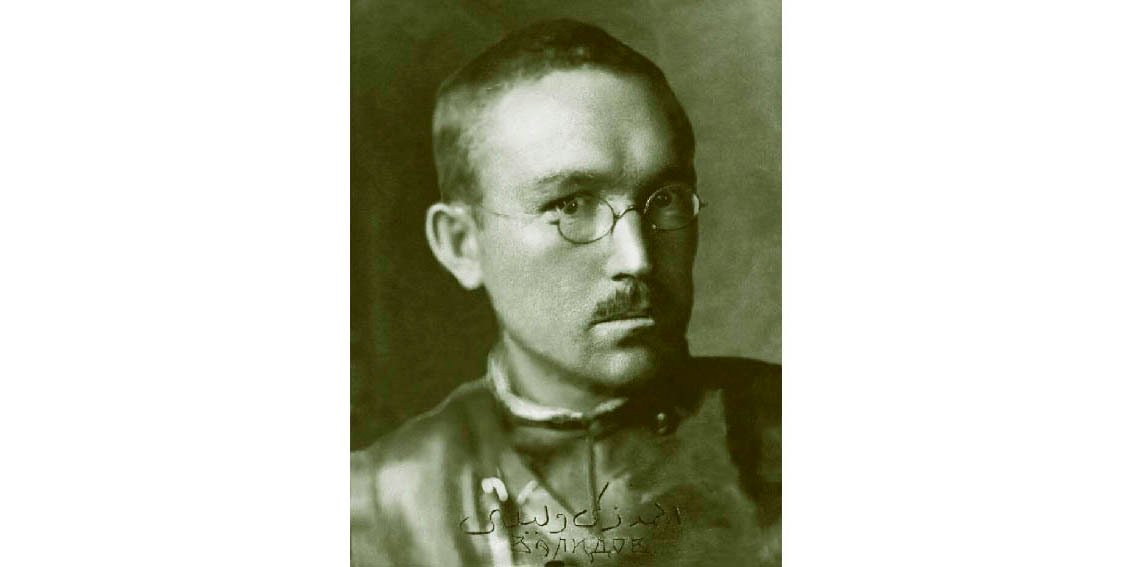

Furthermore, such prominent political intellectuals as Agayev and Gasprinsky, as well as Zeki Velidi Togan, made their chief contributions to Turkish nationalist culture through scientific approaches fostered as part of the branches of Turkology and history.

Early life

Togan was born “Ahmet Zeki Velidi” to an intellectual family on Dec. 10, 1890, in the village of Küzen near Ishimbay in Bashkortostan (now a federal republic in the Russian Federation). His father Ahmedşah taught him Arabic, while his mother Ümmülhayat taught him Persian, even before enrolling at the madrasah of his uncle Habib Neccar, where he studied Arabic literature. He studied Russian throughout this period.

Ahmet Zeki later fled to Kazan to complete his studies at the Qasimiyya madrasah, at which point he found out that his father intended to have him married and work as the imam of his village. After graduation, he taught language and history classes at the Qasamiyya madrasah in Kazan and Osmaniyya madrasah at Ufa, the capital of Bashkortostan. Meanwhile, he met a number of Russian orientalists in Kazan and became interested in the Turkish language and history studies, which would help him to acquire his real reputation in later years.

Revolt and exile

Togan was also heavily involved in local politics. Like many Muslim intellectuals living in the Russian Empire before the 1917 revolution, he tried to gain an active part in the administration of his homeland after the revolution. He was elected as the representative of Bashkiriya to the Assembly of Constitution in 1918, which would later be disassembled by the Bolsheviks, with whom Togan had fought for the independence of Bashkiria. However, after the failure of the Bashkir revolt, Togan attempted to collaborate with Lenin and Stalin, the leaders of the Bolshevik revolution, which also ended without any positive result. Eventually, in 1920, Togan had to flee from the Bolshevik terror and joined the Basmachi revolt in Turkistan together with Enver Pasha, the legendary Turkish ex-commander in chief, against the Bolsheviks.

The Basmachi revolt won some local successes but lost much of its momentum after Enver Pasha’s death in 1922. After fighting for 30 consecutive months, Togan was forced to leave Turkistan forever in 1923 and lived in Afghanistan, Iran and Europe before he eventually decided to settle in Turkey.

Scholar

Togan was a man of scientific study by character, and a politician by obligation. He never ceased reading and studying literary and historical texts. Even in Meshed, during his Iranian exile, he found a lost manuscript from Ibn Fadlan, about whose works he would submit a dissertation in Germany in later years to gain a doctoral degree. He also continued his studies in Herat and Kabul, Afghanistan.

Togan traveled to Turkey in 1925 via India together with Abdulkadir Inan (Fethulkadir Süleyman), who would accompany Togan for many a journey. However, the pair was not allowed to enter due to a lack of visas. Perhaps the Kemalist administration wouldn’t seek to take the risk of allowing the two Turkish rebels involved with Enver Pasha, the greatest rival of Mustafa Kemal, even after his death.

The duo headed to Europe, and for the following 18 months of their stay, met up with orientalists of various nations. In 1925, Hamdullah Suphi, the Minister of Education to the Turkish Republic, invited them to Turkey for their reputation as scholars. Togan began to work for the Translation Office of the ministry. Yet, he asked for a transfer to the Darülfünun (later Istanbul University) to continue his studies more thoroughly, and he was appointed as a professor of Turkish history in Istanbul in 1927.

Togan worked as a professor of history until the First Turkish Congress of History held in 1932, where he had a scientific quarrel with Reşit Galip, a medical doctor, that played a critical role in shaping the cultural and educational orientation of the young Republic, which constituted an apologetic and secularist nationalism intended to prove that the Turks had been a civilized people beginning with their Central Asian ancestors. Reşit Galip defended a no-sense thesis that Central Asia was an inland sea when the ancestors of modern Turks lived there, which was rejected by Togan for obvious reasons. Firstly, there was no scientific proof for such a claim. Secondly, any historical narratives did not support it.

Exile forever

Since Republican friends of Reşit Galip, Sadri Maksudi Arsal and Şemsettin Günaltay continued attacking Togan with and uncivilized attitude, he quit his job at the Darülfünun and traveled to Vienna, where he submitted a doctoral dissertation on Ibn Fadlan in 1935, and he taught as a professor of oriental studies in Austria and Germany until he returned to Turkey in 1939 upon invitation by Hasan Ali Yücel, the minister of education.

However, Togan was among the nationalists who were arrested and tried for Turanism in 1944. He stayed in prison for 15 months before the military court released him. He was acquitted two years later. One year after his acquittal, Togan was reappointed as a professor at Istanbul University.

Togan had the 22nd Orientalism Congress held in Istanbul in 1951. Two years later, he found the Institute of Islamic Studies and became the first chairman of it. He continued his studies at the institute that he founded until his death on July 25, 1970.

Togan devoted his entire life to Turkish studies, particularly the study of the history of the Turkish or Turkic peoples. He is the author of numerous historical studies including “The History of Bashkırts,” “Methodology in Historiography,” “The History of Tatars and Turks,” “An Introduction to General Turkish History” and more. His translation of and treatise on the Persian “Oğuzname” (the name given to legends of Turks) excerpted from the “Jami al-Tawarih” (Collection of Histories) of Rashid al-Din Hamadani, the great Ilkhanid historian, was published posthumously.

Last Updated on May 15, 2020 3:26 pm by Irem Yaşar

Discussion about this post