Some 659 dovecotes for pigeons, built centuries ago inside a very steep rock face on a hill at the Ani Ruins located near the middle of two deep bottlenecks of the Arpaçay River on the Turkish-Armenian border, have raised a lot of interest among people.

Ani was ruled by the Urartus, Scythians, Persians, Macedonians, Seleucids, Arsakids, Sasanians and Gamsaragans before it was seized by Muslim armies in 643. It was then controlled by the Bagrationis from 884 to 1045 and by the Byzantine Empire from 1045 to 1064.

Known in history as the “40-Ported City,” “The City with 100,000 Inhabitants” and “The Cradle of Civilization” and named in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2016, Ani was conquered by Sultan Alparslan on Aug. 16, 1064.

After the Seljuk/Shaddadids rule, both the Georgians and then the Mongols took over Ani. Following 80 years of uninterrupted control under the Ilkhanates, Ani came under the rule of the Khanate of Golden Horde, the Jalairids, the Karakoyuns, the Timurid Empire, the Akkoyuns, the Ottomans and the Russian Tsardom. Ani finally became part of the territory of the Republic of Turkey in 1920.

While various civilizations lived in the city, built on an area of 85 hectares, Christians and Muslims lived side by side and its people spoke at least six languages including Armenian, Greek, Turkish, Arabic, Georgian and Persian from 970 to 1320.

Ani was the heart of multi-dimensional trade between the East and the West in medieval times and its commercial mobility extended to China, India, Russia, Europe and Africa. Egyptian cotton and Chinese silk were sold in the city’s markets.

Approximately 25 buildings, including mosques, cathedrals, palaces, churches, monasteries, fire temples, baths, walls, bridges and a closed passage, some parts of which have been destroyed, have managed to survive.

Nearly 1,500 underground structures in 32 regions of five valleys, where a significant portion of the Ani population lived, shed light on the history of the city.

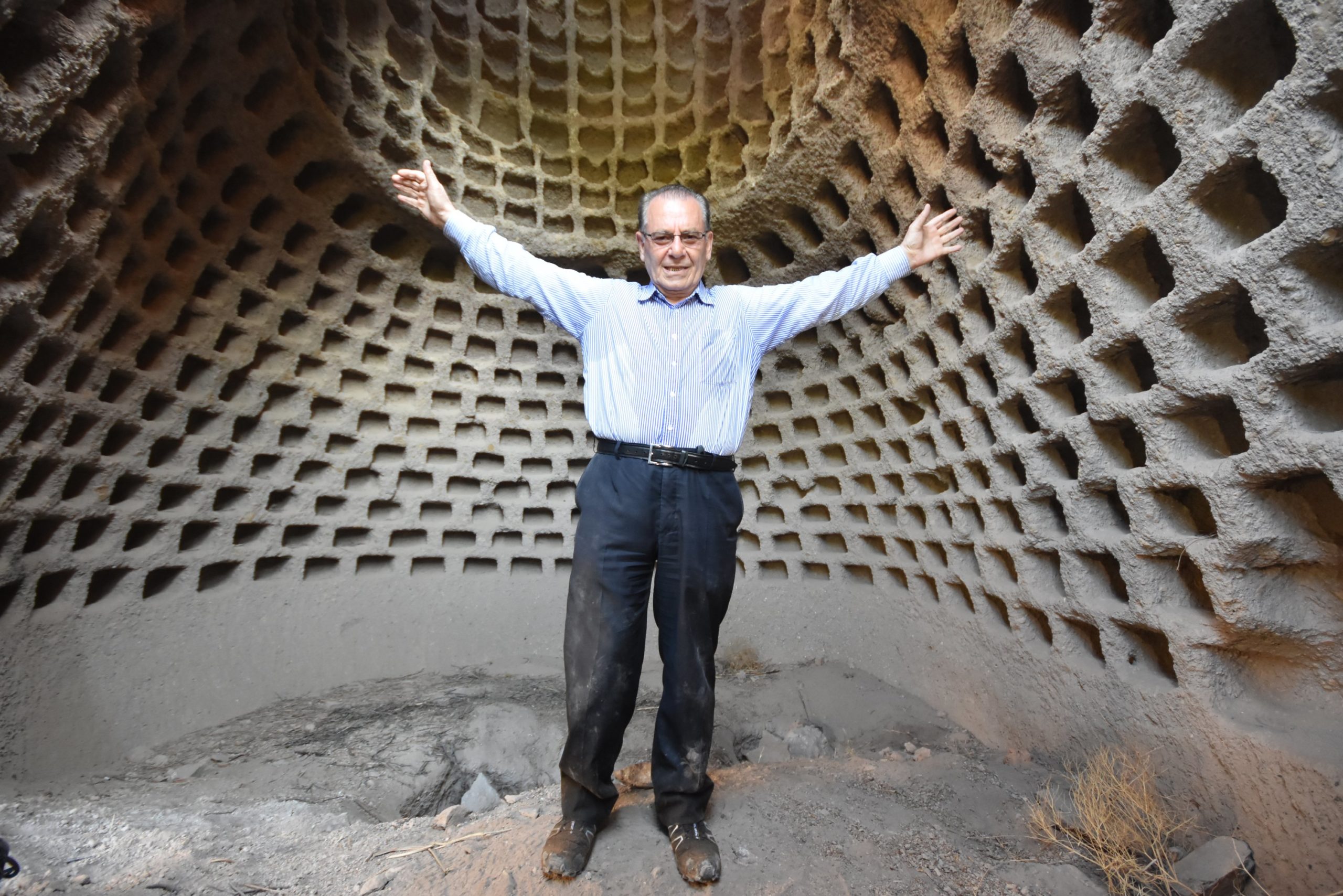

One of the most admirable is the dovecotes carved into a rock face formed by tuff, which is a mostly light-colored, slightly porous type of sedimentary stone composed of ash, sand and lava particles spewed by volcanoes on a hill on the opposite bank of the Bostanlar Creek, located in the west part of Ani. The subterranean structure embodies fine craftsmanship and has the appearance of a honeycomb.

Sezai Yazıcı, a researcher and author who has written four books on Ani, and a team of journalists from Anadolu Agency (AA) reached the dovecotes, which is 150 to 170 meters away from the road, after a challenging climb with the help of a ladder and rope. The structure is located in the rocks of a steep hill. The dovecotes are 2.5 kilometers from the entrance gate of Ani and 1,100 meters above the point where the Alaca Stream meets the Arpaçay River.

Sezai Yazıcı told AA that he carried out the first systematic study on Ani’s underground structures in Turkey.

Indicating that he climbed to the dovecotes in Ani for the first time in 2014, Yazıcı said: “I have been working on this area since 2010. I presented the first systematic study on the dovecotes and Ani caves in Turkey at a symposium at Kafkas University.”

Pigeonholes Carved into Tuff

Yazıcı has been studying the dovecotes around Bostanlar Creek for years. “Although it is known that there are 1,013 caves in five different valleys and 32 regions surrounding Ani, we have determined the presence of around 1,500 caves as a result of our new studies. The dovecotes in Ani are one of the most sophisticated areas. It is full of pigeonholes, 659 from ceiling to floor.”

Providing information about the structure of the dovecotes in pigeon nest measurements, Yazıcı noted: “Pigeonholes in the lower rows of the dovecotes are 30, 28 or 24 centimeters wide and 25, 24 or 11 centimeters deep, while their height is 11 centimeters. The east-west front of this area is 4 meters, the south-north front is 6.25 meters in size.”

“It is estimated that pigeons here were used in the postal service. There are two holes in the upper dome. We can tell that light comes from one of the holes to the southeast and pigeons come in and out from the other. This can also be considered a very sophisticated structure built to obtain quality fertilizer.”

He pointed out that pigeon breeding was carried out for different purposes in the past. “It is hard to imagine a classic postal service consisting of pigeons. We also have seen that the fertilizers obtained from the dovecotes in Bostanlar Creek have proven very useful in vegetable and fruit production here,” he added.

Last Updated on May 28, 2020 4:51 pm by Irem Yaşar

Discussion about this post