Identity has been a central issue for all modernist thinkers, not least those of a nationalist persuasion. Before the advent of the nation-state, ordinary people, philosophers and religious leaders alike would generally define themselves by their faith. In any case, most would consider themselves a part of a local community, where the majority would stay their entire lives. And thus, there was no need for invented rational identities such as race and nation.

After the great turmoil that followed the French Revolution, nationalism became a widespread ideology – first among Europeans, and eventually the whole world. The initial nationalists to rise within the Ottoman Empire emerged among the Greeks, who were in close contact with Western European thought and succeeded in separating from the Empire to found modern Greece. And the last to claim a slimly defined national identity were the Turks, the original founders of the empire.

It’s interesting to note the first Turkish nationalists emerged from another empire – that presided over by Russia. This makes sense since we humans tend to perceive differences sooner than similarities. Turkish intellectuals living in Russia or territories under Russian influence were quicker to realize their national identity than their fellow Turks living in the Ottoman Empire. This broadly explains how the initial nationalist cadre who surrounded Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish nation-state, included exiles from Russia, Central Asia, Crimea and Transcaucasia.

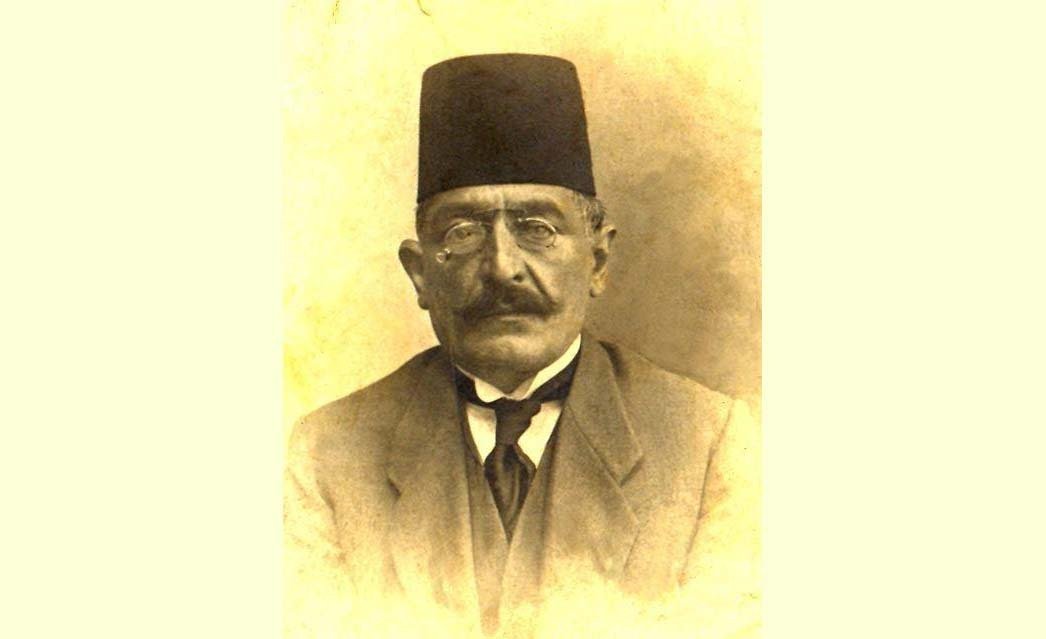

The case of Ahmet Ağaoğlu is perhaps the most distinguished one among others. Indeed, Ağaoğlu was not even a proper nationalist and changed his ideas frequently until he became akin to Atatürk. His political position also changed over the duration of Atatürk’s rule and afterward. In his early life, Ağaoğlu thought of himself as Persian, before declaring his identity Muslim, Russian Muslim, Caucasian Muslim and Turkish Muslim. Eventually, he came to refer to himself as simply a Turk.

Early life

Ahmet Ağaoğlu, or “Ahmet Bey Ağayev,” was born to a Shiite Turkish family in 1869 in the town of Shusha in the Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, which was then under Russian control. His father Mirza Hasan was a wealthy trader, who was fond of reading and hunting. “He lived and died a happy man,” recalled Ağaoğlu in his incompleted memoirs, “Even the Russian invasion didn’t bother him. They gave estate-holders titles of nobility. So, why should my father, son of nobles and ağa of Kurteli, be bothered or have cause to reflect?” Mirza Hasan thought of himself as a Muslim, a Shiite and a member of the Kurteli tribe, but not as a Turk, the identity his son Ahmet would devote his life to. Ağaoğlu’s mother Taze Hanım was from the Sarıcı Ali tribe, another respected Turkish tribe.

Ağaoğlu was first schooled in the local “mahalle mektebi” (a traditional elementary school), where he was taught in Turkish and Persian. In Turkish, he memorized Fuzuli’s “Leyla and Mecnun” and the “Ferişte” (“Angel”) of Mullah Cami at school. In Persian, he read “Bostan ve Gülistan” (Orchard and Rose Garden) from Sadi, the divan of Hafiz, history of Nadirşah, et cetera. He also learned Arabic from a private tutor at home.

After his initial studies, Ağaoğlu enrolled at high school in Tbilisi. He managed to read and write Russian thanking to the appeal of Russian books according to his own recalling. After graduating from high school, he moved to Paris in order to study history and philology at Sorbonne.

Azerbaijani nationalist

Ağaoğlu began writing as early as his high school years. He published some pieces in Turkish in local journals in Tbilisi. He also published in French when he was in Paris.

While in Paris, Ağaoğlu met some members of the Committee of Union and Progress (CPU), which would have a huge impact on his later life. Yet, he returned to Azerbaijan in 1894 to teach language and literature at high school after completing his studies at Sorbonne.

During the 1890s and early 1900s, Ağaoğlu was a part of the national Azerbaijani struggle against the Russian invasion of the Caucasus. After the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, Ağaoğlu fled to Turkey due to Russian political pressure, which changed his fate forever.

Turkish nationalist

Ağaoğlu didn’t feel as alienated in Istanbul as he had in Paris, becoming a familiar figure easily among the intellectuals of Ottoman Istanbul. He wrote for periodicals including Filibeli Ahmed Hilmi’s “Hikmet” and Mehmet Akif and Eşref Edip’s “Sebilürreşad,” while fulfilling work as an educational inspector. He also worked as the director of the Süleymaniye Library.

Ağaoğlu took the side of the nationalists in the nationalism-Islamism debate that raged at the time and was one of the founders of the “Türk Ocağı” (Turkish Hearth) association and “Türk Yurdu” (Turkish Homeland) journal. He also was a member of the CPU headquarters and was elected as a member of parliament for Afyon province.

Ağaoğlu stayed in Azerbaijan for a while after the Russian Revolution and was elected as a member of the Azerbaijani parliament. However, the British police arrested him in Istanbul while on the way to Paris in order to negotiate in the name of an independent Azerbaijan. He was exiled to Limni and Malta, from where he moved to Ankara in 1921 to join Mustafa Kemal for the national struggle in Anatolia against the Greek invasion.

Ağaoğlu seems to have tried his best to gain a free, nationalist Azerbaijan; however, the flow of historical events drove him toward the Turkish nationalist movement. Finally, he became a constant part of the inner circle of Kemal, who would become the “eternal leader” of Turkey.

Liberal

It’s a curious matter of history that Atatürk recruited people like Ağaoğlu, showing how he gathered up various rootless intellectuals from Russian territories in a way not dissimilar from the Ottoman recruitment of Christian youth for the Janissaries over previous centuries. Great authors of the likes of Yusuf Akçura and Ahmet Ağaoğlu never complained of anything and did whatever they were ordered by their paternal leader.

Ağaoğlu’s participation in the Serbest Cumhuriyet Fırkası (Liberal Republican Party) in 1930, upon the orders of Atatürk, was another ironic gesture of loyalty. The public showed great enthusiasm for the Serbest Fırka – to the degree that its own leaders decided to close it down and continue with the single-party rule, which great writer Kemal Tahir would call as “madrabazlık” (swindling) in his novel written on the history of the Serbest Fırka.

Ağaoğlu was no swindler. He showed only loyalty to the leader and his regime, which gave him a place after he lost his homeland to the Bolshevik imperialism. He left politics after the Serbest Fırka incident and became a professor at Istanbul University.

However, the repression of Kemalist rule would ultimately extend over its loyal follower, Ağaoğlu, too. Ağaoğlu would go on to publish a journal called “Akın” (Torrent), in which he criticized İnönü government’s statism, calling for economic liberalism. The government banned the journal and Ağaoğlu was fired from his position at the university in 1933. Before the official closure, Atatürk warned Ağaoğlu about his displeasure for the ideas Ağaoğlu defended in the journal. Yet, Ağaoğlu told him that he would not like to shut down the operation, which made Atatürk very angry. The “eternal leader” reminded Ağaoğlu that he was an Azerbaijani refugee in Turkey, thereby living at the leader’s indulgence.

Ağaoğlu was a vehement defender of individualism and liberalism. In terms of his nationalism, we cannot easily refer to him as a liberal as in the Western sense. Rather, he was against a holistic and statist economic and political model. He published two volumes to defend his libertarian thoughts, namely “Devlet ve Ferd” (The State and the Individual) and “Serbest İnsanlar Ülkesinde” (In the Land of Free Men). I believe Ağaoğlu would become a part of the Democrat Party (DP) of Adnan Menderes had he lived 10 more years – which might have been proven by his son Samed Ağaoğlu’s subsequent participation in DP. Ağaoğlu died on May 19, 1939, in Istanbul.

Last Updated on May 29, 2020 4:23 pm

Discussion about this post