Ottoman Levantine cities had existed between the 17th and 20th centuries, with diverse populations of Christian Greeks and Armenians, French and Italian families, Jews, Muslim Turks and Arabs.

But centuries of coexistence and multiculturalism came under threat soon after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, and their decline started as the map of the Middle East was redrawn.

Philip Mansel, an award-winning historian, sat with TRT World for an interview to discuss Levantine bastions such as Aleppo, Alexandria and Istanbul, and the rise of populist movements in today’s world.

A smartly, yet casually dressed historian, Mansel exudes an air of humility and approachability.

An expert on France and the Middle East, Mansel has written several books, including Aleppo: The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Great Merchant City, and Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean.

A day before the interview, Mansel spoke at the second Beyoglu Levantine Conference, organised by the Levantine Heritage Association and the Municipality of Beyoglu between November 10-12, 2017.

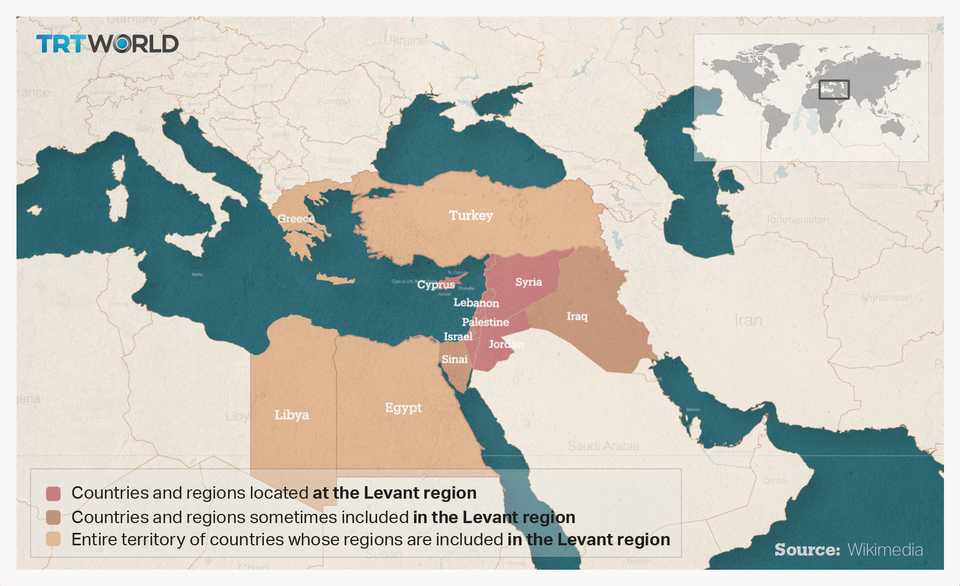

How would you define “the Levant”?

PHILIP MANSEL: The Levant is a region of the eastern Mediterranean where the sun rises: Le soleilseleveaulevant. And more particularly in the modern era, it’s the period after 1516 where the whole area is under the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Empire encourages foreign merchants to move to certain cities for trade and it’s really very easy for travellers going there, for missionaries, priests in Catholic orders, and certain diversity is established in cities like Istanbul, Izmir, Alexandria, and Beirut.

You mentioned [in your speech] that “Vulnerability is a characteristic of many Levantine cities.” What do you mean by that?

This mixture of peoples, of Muslims, Christians, Jews, Turks, Greeks, Kurds, Armenians, many other races, which you saw in these cities and also Aleppo was a great early Levantine city. It could be vulnerable. This could lead to explosions and riots; they’re in fact surprisingly rare. For example. And of course, the interest of foreign powers, always great in the region, particularly when the Ottoman Empire got weaker. [In] 1882 there were riots between Egyptians and Maltese in Alexandria; and then Britain bombards Alexandria and in fact it destroys much of Alexandria. That’s an example of vulnerability. For example, you see incredible photographs and films of [Izmir] burning [in 1922, during Turkey’s Independence War]. Often there were riots in Istanbul; 1895-1896. [Then there’s mob attacks against non-Muslim population in] 1955 which provoked the departure of many Greeks and Armenians.

But in fact this vulnerability was no greater than, say, Paris with all its revolutions, or Saint Petersburg with its Russian Revolution a hundred years ago which really diminished the city permanently and led to grass growing in the street and a huge exodus of people.

But maybe in a Levantine city you feel more of an edge, more of the daily possibility of some spark leading to an explosion. Certainly in Beirut you have this feeling anything could happen … there could be a return of violence. That’s why the Lebanese are so determined to enjoy themselves, because “we must eat drink and be merry; for tomorrow we die”.

You mention Aleppo among other Levantine cities but it’s not a port city. So how is it similar to the other cities and how is it different?

PM: Aleppo is fascinating. It’s not a Levantine port city but it’s only 75 kilometres from the Mediterranean. That’s not a lot. It had this port Iskenderun where there was always international trade from the 16th century.

[T]he two cities were interconnected and Aleppo—because it was a great trading centre, really because of geography. It’s on every trade route from the Gulf from Iran to the Caucasus from the Hijaz—it was a natural entrepot and there were foreign merchants there; Indians, Armenians, Europeans and consuls from 1516 [onwards].

And when Aleppo sank in the 17th century, Izmir became the new Aleppo, the new great world city of trade where Asia and Europe come shopping for each other. And many people from many families moved between Aleppo and Alexandria and Izmir.

Do you still think Izmir is a Levantine city?

PM: It’s a very international city. It feels quite different than Istanbul and other Turkish cities. It feels like a Mediterranean city. It’s trying to reconnect with its past with our Levantine Heritage Foundation: many other groups in Izmir, universities, the very good city museum, about its past, Izmir Chamber of Commerce is interested, we’ve had a conference there. And I notice there’s some fantastic interpreters and translators from Izmir still.

Of course its past, before 1922, is something extraordinary—it was like a Hong Kong on the Aegean.

Aleppo was under Ottoman rule. And you said [in your speech at the Levantine Conference] that while others revolted, Aleppo didn’t. Why was that?

PM: It’s a very good question. It was always a trading city. It was more peaceful than Damascus. And with this proverb, “If you do business with a dog, please call him sir,” they’re putting trade first. So maybe that trading spirit just made them carry on working while all the other cities of Syria were in revolt—almost all. Otherwise I don’t know; there may have been a clever governor or an army commander but it was late.

But the city is now divided. There are some areas I believe are controlled by Kurdish militias, many Armenians have left—it was a great Armenian city of the 16th century, many have gone to Armenia, many have gone to Canada or wherever they can go. And, as you know, many people from Aleppo ended up in Diyarbakir or Gaziantep or Istanbul. It’s a huge exodus. It’s the last of the mixed Ottoman cities to go: Istanbul, Izmir, Beirut, Sarajevo, they’ve all become divided or homogenised. Only Aleppo remained.

And the huge exodus. It’s very hard to get any [non-regime] news how many people have left, how many people are getting back, at one point, the city of two and a half million was reduced to five hundred thousand, I think. Maybe things are improving now. They could hardly have gotten worse.

And the suffering was worse than in Damascus. Horrific destruction of schools and hospitals and mosques and churches in these barrel bombs coming from planes, Syrian [regime] planes onto sometimes civilian areas.

You mentioned in your talk “the long awaited French occupation of Aleppo [in 1920]”. How do you see Ottoman-French relationship historically?

PM: Commercially Marseille lived off trade with the Levant from the 17th century. Huge French trade in Izmir, Aleppo, Alexandria, Istanbul. Culturally there were French missions from 1625 all over the Ottoman Empire, beginning to preach to local Christians, eventually founding schools where Muslims and Jews also went in the 19th century.

For example, some Turkish writers and politicians; [such as the 19th century author, poet, and playwright] Halit Ziya Usakligil, he went to a French school in Izmir. And many other examples. [Ottoman statesman] Talat Pasha had been to a French-Jewish school teaching for Alliance Israelite Universelle, and many others.

French becomes a common language for different communities and it’s the language of the world of modernity and science and education. [That’s why] people want to learn it: [Ottoman statesman] Enver Pasha knew it; [modern Turkey’s founder] Mustafa Kemal [Ataturk] knew it—and by the way Mustafa Kemal the great Turkish national leader, he’s also got a Levantine aspect: he’s from [Thessaloniki]. He would have met many people from different races, above all Jews, it was a majority-Jewish city, and [Thessaloniki] was more open, less oppressed than Istanbul under Abdulhamid.

He went to an Ottoman school where there were some French. He learned French also from WWI, read French books… He had a Levantine friend, Madame Carine, living in Beyoglu. His letters to her survive in French.

And he brought French laws under the republic. Many aspects of French Third Republic laws were… the concept of “laiklik” [laicite]… is French. And then there’s the French alliance with the Ottoman Empire; it more or less works militarily.

When the Ottoman Empire was very weak, after the siege of Vienna; they’re defeated, they think the Austrian armies are going to come to Istanbul. Then the French are circling like vultures like everybody else: “Which bits shall we have?” And some local Christian leaders, the patriarchs in Syria, encouraged this: “Come and liberate us!” they wrote to Louis the XIV. “Forget about the Rhine, think of the Euphrates.”

What do you foresee about Aleppo?

PM: I don’t know. Anything is possible. The [Syrian regime] hasn’t changed much. It’s the same as it was before the civil war. Will it change? Or will the situation go on where Armenian Syrians, not only Sunni Muslims, feel disenfranchised and strongly dislike the Assad family and the present [Syrian regime]? No one can deny there was strong hatred. Of course it was also sowed by some foreign governments and foreign movements but it was also local and Syrian. It’s a dictatorship. They’ll reconstruct in a certain way and companies close to the government will benefit. We’ll see what happens.

Do you think all Levantine cities are dead?

PM: People think Levantine cities were doomed. But in fact we’re having new Levantine cities whereby every modern city like Amsterdam or London or Paris, they’re all so international and many languages [and betraying] a certain vulnerability. A certain distance from the hinterland. I mean London is completely unlike Northern England for example. Polyglotism—very modern. And the role of international bodies and international companies perhaps they’re replacing embassies and consulates as sort of vehicles of modernisation.

And the indispensable references for people’s lives like the role of consulates in Izmir or Aleppo or Alexandria’s hugely important. People wanted to be beratli [enjoying the privileges bestowed upon the non-Muslim Ottoman population] and you learned new techniques from consuls and their officials. For example they ran the international quarantine in some ports. One thing that kept the Ottoman Empire back was disease and lack of quarantines and plague control.

What else? I think one reason why Levantine cities have been slightly forgotten is there have been very few great writers from them or great painters. Maybe we’ll find some more. There was Kavafis from Alexandria his poems are wonderful and that’s about it. Some novelists…

I think Levantine cities have a message for us: Different people can get along if they follow the law, if the government favours this.

But right now everybody is talking about separation. There’s Brexit, there’s the Catalans…

[I]t’s no better when you’re just left alone with Turks or English or Spanish… People will still quarrel and be violent. Ataturk made a wonderful remark after the destruction of Izmir [during Turkey’s Independence War] when somebody asked him “Well now what do we do?” He said: “Now we’ll fight among ourselves.”

He thought nationalism was the only way to save Turkey. And it was the fashion of the day. But he missed many aspects of his youth and he would dance these Rumeli dances… “Mixed villages have the best tunes,” according to musical historians who go around the Balkans and I think mixed cities have the best tunes also.

Living in London, I’ve seen it go from quite a dull English city where you could not find a proper cup of espresso, and now it is much more interesting and lively and more cheerful as many people have told me. Better food and coffee.

And I think it’s important to show that not everybody was controlled by race and religion and you could have multiple identities. And all these Turkish national leaders who spoke French also, Arab national leaders spoke Turkish also, in their youth in Istanbul. Many people could switch identity and from Greek become Italian or French. Like the Ottoman imperial family [expelled after the formation of the Republic from Turkey] settled down in France, although a lot of them have come back.

Nothing is fixed. Things are flexible. I think in a way Barcelona may be an Ottoman city because the coast of Catalonia doesn’t want independence I think; that’s where the pro-Spanish feeling is. It’s the countryside that’s more Catalan. And we have other Levantine cities in Europe like London, Paris, Marseille, Odessa, who knows what will happen [in the Ukraine] now.

We forget—globalisation isn’t new. The Mediterranean was quite a global area in the Middle Ages when all these ports spoke Italian, or bad Italian. It’s quite interesting the lingua franca which went on in Istanbul; the ulema [scholars] didn’t want [locals] to learn proper Italian. I think that’s proven in Morocco and Tunisia [too]. But they had to communicate for trade and war and ships so they had this broken Italian which a lot of people spoke in the ports and in Izmir and Istanbul and then after 1830 say French takes over and it was a global language and very, very widely spoken. I knew an old English lady who could remember Istanbul before 1914 and I said, “What was it like?” and she said, “It was all French!” Everybody spoke French. She had married a Turk, a Muslim.

I think that’s all I have to say.

Additional reporting by Murat Sofuoglu

Discussion about this post