Earlier this year, Israel began exporting natural gas. It was a significant development for a country which just a few years ago, was almost entirely dependent on imports to run factories and power plants.

What led to Israel’s energy transformation was the discovery of two giant offshore fields in the eastern Mediterranean.

The discovery of the Tamar gas field off the Israeli coast in 2009, and months later, the Leviathan field find, changed the hydrocarbon outlook of the region overnight.

These vast reserves have fuelled Tel Aviv’s dream of becoming a major player, aspiring to even one day supply Europe via liquified natural gas (LNG) exports.

Since then, half a dozen countries, which have shores on the eastern Mediterranean, have intensified efforts to find their own reserves. A few have succeeded – with big rewards.

For example, Egypt struck the massive Zohr gas field 4,000 metres below sea level in 2015. It holds an estimated 800 billion cubic meters (BCM) of gas.

It is the largest field so far found in the eastern Mediterranean. As a comparison, Zohr is producing 2.7 billion cubic feet (bcfd) of gas per day – that one field alone is more than half of Pakistan’s total gas output.

Greek Cyprus administration also found gas in the deepwater Calypso field in 2018.

According to the US Geological Survey, just the Levant Basin, which includes the waters of Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Palestine and the divided island of Cyprus, contains 122 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of gas.

Energy consulting firm, Wood Mackenzie, estimates that total gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean are about 125 TCF.

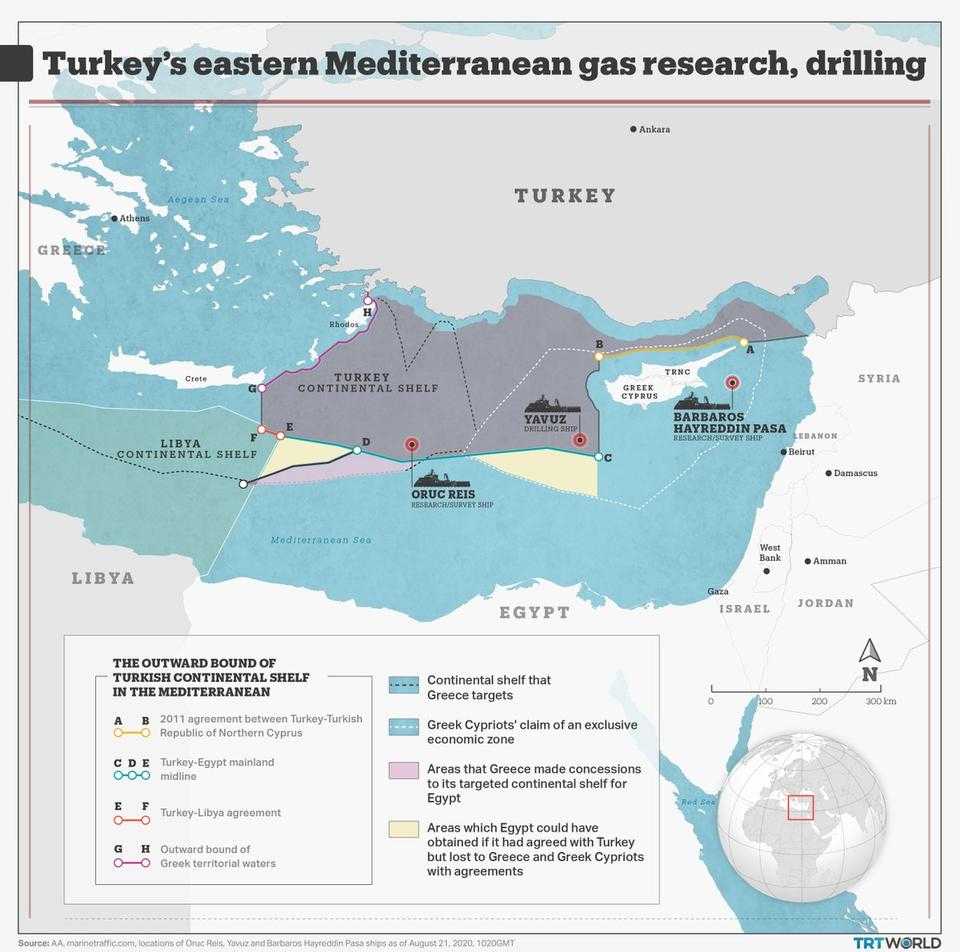

Driven by these discoveries, Ankara decided in 2017 to expedite their own search in the region.

It bought a seismic vessel and three drilling ships — Fatih, Yavuz and Kanuni — to begin the search in the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

Turkey meets almost all its gas needs from imports, a move that costs the country billions of dollars, a major strain on its foreign exchange reserves.

Its exploration efforts paid off as it announced a large gas find in the Black Sea last month.

But Turkey’s exploration in the eastern Mediterranean faces roadblocks from Greece and Greek Cypriots – they have drilled wells in contested offshore territories but do not want Turkey to do the same.

Turkey, a regional economic power, has been excluded from maritime agreements including those that Greece, Israel and Greek Cyprus have used to demarcate offshore gas blocks between themselves.

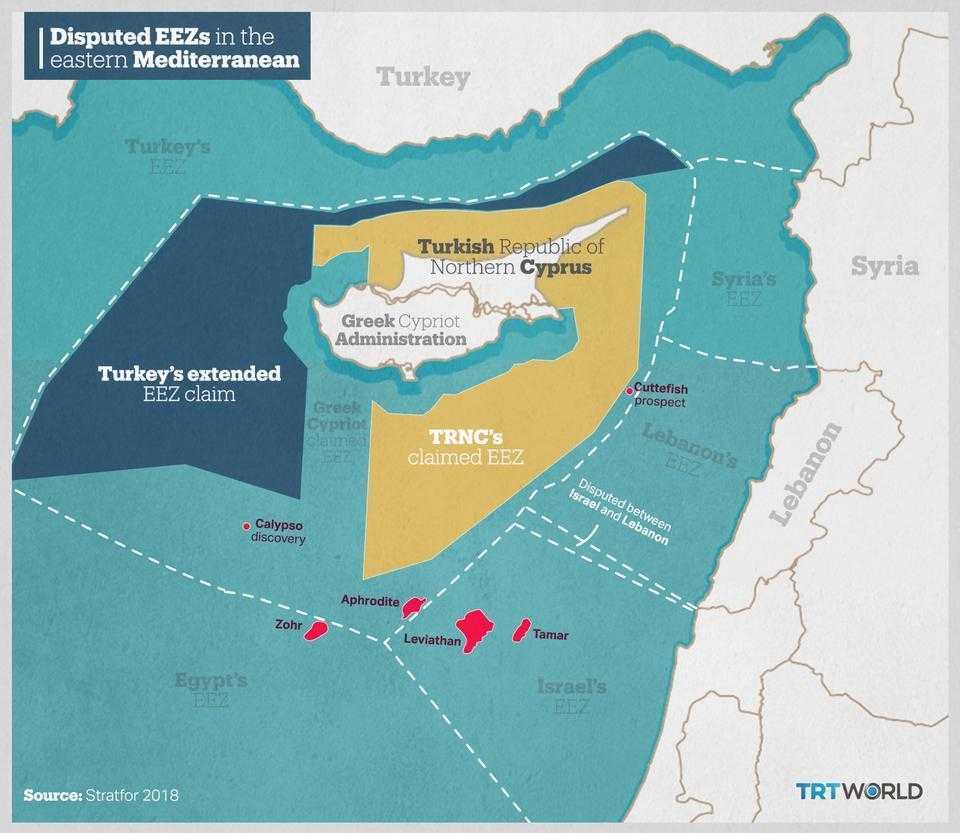

A major issue is the exploration work being carried out in the waters claimed by Greek Cyprus. The tiny island has been since the 1970s divided into two parts — one under the influence of Greece, and the other inhabited by Turkish Cypriots

Ankara says that the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) must have a share in the offshore resources.

The Greek Cypriot Administration has awarded exploration concessions to multinational companies in offshore regions west and southeast of the island without consulting with the TRNC.

Turkey has all along pushed for joint exploration, but the Greek Cypriot Administration has rejected the idea, saying other issues must be settled before the prospect of joint drilling can be discussed.

Similarly, Greece is trying to enforce exclusive economic zone (EEZ) rights around its many tiny islands in the Aegean Sea. An EEZ is an exclusive area of a country extending 200 nautical miles from its shore.

This leaves Turkey with a tiny offshore stretch and almost nothing in the eastern Mediterranean – something unacceptable to Ankara.

Turkey has the longest coastline along the eastern Mediterranean. If Southern Cyprus and Greece have their way, Turkey’s territorial claim shrinks to 41,000 square kilometres from what Ankara assesses should be 189,000 square kilometres.

The involvement of European petroleum giants further complicates the situation. Italian ENI is the operator of the Zohr field, and France’s Total has stakes in fields off Greek Cyprus.

Discussion about this post