His cartoonish visage is unmistakable. Yet, his name evades collective memory. One of the most storied and colorful figures from the Yeşilçam era, Cevat Kurtuluş was a film extra, roaming the famously nostalgic street off İstiklal Avenue that has become synonymous with Turkey’s golden age of cinema. Lasting from 1952 to 1977, its copious movies are marked by the site-specific social ecology from which they emerged, similar to Broadway or Hollywood.

The man had a rotund midsection, a bulbous schnoz and flappy ears. He had a goofy smile that beamed through the perfect circles of his wide eyes, lightening his infectious smile. Often playing subordinate types such as the waiter, butler or driver, whether garbed in overalls or a tuxedo, his comic air could spark a flame following even the deadest dud of a bad joke, gifted with the physical timing of a silent actor.

In his hands, the 8-millimeter camera that he learned to wield moves with an erratic swing, capturing uncanny slices of his personalized world with a surprisingly genuine knack for showing the fleeting allure and informal atmosphere that also makes his sense of humor tick. Portrayals of fellow actors, like Comma and Dot, a duo out for cheap thrills, are as richly documented as his collegial impersonators of cross-dressers, urbanites and villagers.

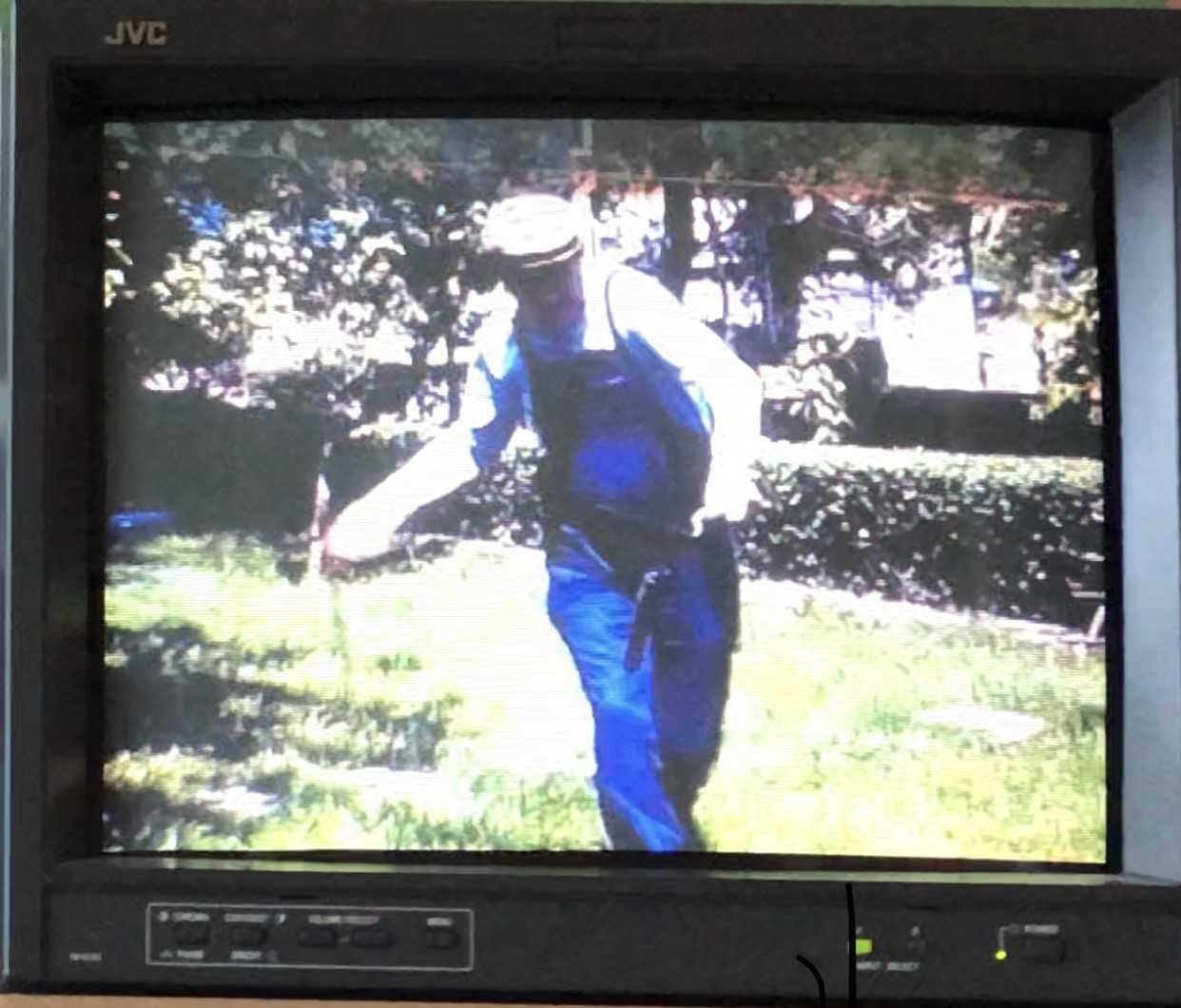

Suited to the nines in black-and-white attire, he skips for a dance with a trio of misfits, including a hefty, rural man in a white cap, beside a short, plaid-jacketed gent of the night and finally a bewigged bloke in a dress. The latter two form an unlikely couple as they promenade arm-in-arm within a bucolic setting, surrounded by forest on all sides. The revelers do not hold back their laughter. In true theatrical tradition, they are out to make fun of human role-playing.

Mediator of unknowns

Ege Berensel installed his exploratory homage to Kurtuluş via 12 vintage television monitors in four exhibition rooms throughout the multistory, seaside apartment complex currently housing AVTO, wherein Istanbul’s more intrepid art-goers will also delight in the scenic vistas along the Bosphorus thoroughfare of Kuruçeşme Avenue. In the vein of the late avant-garde auteur Jonas Mekas, Berensel concocted a sequential potpourri of spliced, found footage.

Recovered from Istanbul’s undiscovered troves of historical memorabilia strewn across the flea markets and junkyards that punctuate the sprawling cityscape with seductive abandon, Berensel spent about 15 years poring over the 8-millimeter reels that Kurtuluş shot with uninhibited joy and curiosity. Now, the collection belongs to the Kurtuluş family, many of whom are also depicted on casual, summery days through his roving lens.

Titled as his 2019 series, “Extra: Filmogram 1-12,” Berensel’s experimental films flash at AVTO with unrelenting intrigue, projecting a kind of insomniac grab that might trigger a flagrant renunciation of time’s passage from its unsuspecting audience. And with a special ear for melding original soundtrack to the soundless moving images on display, speakers set at the foot of the screens blare with unhinged, percussive noise.

The aggressive first impressions styled by Berensel’s background music are reminiscent of that produced by Glenn Ligon for the pair of videos he screened as part of his contribution to the 16th Istanbul Biennial, “Taksim 1 and 2.” And the videography demonstrates an angle on settings that, at once, might seem entirely normal, but when reflected through an artist’s singular recording, becomes otherworldly.

In light of recent creations

Inside each of the quartet of exhibition rooms, trios of monitors are propped up to display the Kurtuluş remix that Berensel devised out of his monolithic field of interests in which he immerses himself. Based in Ankara, the artist was born in Muğla in 1968 and despite a stint lecturing on aesthetics and criticism at Middle East Technical University (METU) in 2013, has generally shied away from entering the spotlights of the art world as a name brand creator.

But where some may take one step back, AVTO leaps two steps forward, sharing with Istanbul an altogether unique approach to the art space model, transforming the normative gallery view with its anti-capitalistic stance steeped in the Milanese milieu in which co-founder Sarp Özer received his education in curatorial studies. For the current show, “Cevdat Kurtuluş,” AVTO and Berensel deep dive into the subconscious imagination of Turkish popular culture.

For their public exhibition, the team AVTO wrote the following: “Scrutinizing how film operates through what is rendered tacit and explicit, ‘Cevat Kurtuluş’ is a visual research project that emanates from the 8 mm film records of theatre and cinema actor Cevat Kurtuluş. The work attempts to shed light on the Yeşilçam Cinema era’s previously off-screen space, imaginary-space, labor-space obscured by the camera.”

The films of Kurtuluş invite seers into a world that, until Berensel embarked on his investigatory practice, has remained largely invisible. There is a clarity to his moments of capture, suffused with a candid honesty that enshrines them as valuable documents in the history of Turkey’s cultural sector. In Berensel’s hands, the environments in which film professionals worked and lived in the mid-20th century Istanbul are freshly reevaluated.

There is an abundance of the slapstick creative energy that burst around Kurtuluş as his light-hearted presence showered those around him with a positive levity that appeared to instill coworkers and family alike with buoyant happiness. Despite the gravity of the political situations that were then curtaining Turkish citizens behind the walls and fears of the Cold War, the Yeşilçam era of cinema retorted a powerful, tragicomic mockery of the human condition.

Among the reels in color, such as for Berensel’s “Extra: Filmogram 03,” Kurtuluş squats on a vibrant green lawn, wearing bright, cobalt-hued denim. A woman in a muted purple headscarf looks on with a peculiar interest, standing in front of a simple country house painted sky blue. Her red dress almost glows beside a pair of long-haired dogs. In his worker’s beret, Kurtuluş is then seen wrapping his arms around two costumed confidants, all waiting to shoot.

The hulking jokester of a man then, runs headlong over the grass, past a film camera, where he stops to talk with the crew. Everyone lounges about under the sun, making merry and whiling away the day as they watch Kurtuluş give a performance. Hardly prosaic, Berensel conveyed something of the magic of cinema, the art of realizing the moveable imagination with a mechanical version of the eye, which remembers exactly, instantly, even if obscurely.

Last Updated on Mar 16, 2020 1:55 pm

Discussion about this post