The man had appeared earlier in his visions, a recurring hero of a protagonist who walks the line between reality and art in the mind of Antonio Cosentino. He is block-headed with oversized teeth and a stripe of baldness clean from his forehead to the back of his neck, like a wide ski trail, bordered by tufts of black hair that spike up behind his elephantine ears. But he is a dapper fellow, dressed in a casual white suit.

Where the figure had appeared before in Cosentino’s paintings, he emerges fresh for “Jpeg Archipelago,” sculpted in wood as the piece, “August” (2020). The single button of his dress coat protrudes exactly parallel with the watch he wears on his left wrist. His unstained, bleached pants are hiked up above his ankles. His shoes are an elegant black and white. If he were animated, he might start tapping.

Instead, the curious chap stands, motionless, beside a raw block of wood, perhaps a relative of his origins, the substance from which he was cut. His expression ages somewhat in a large-scale charcoal piece on paper, “Haygaz” (2020), that serves as the centerpiece of the floor installation, in which the features of Cosentino’s peculiar creative output are lit and form through neon displays of place names and from tin structures, such as “Aura Boat” (2020).

In the winter of 2018, Cosentino showed his 2013 tin sculpture, “The Stelyanos Hrisopulos,” at an alternative gallery called, Riverrun. The piece is a model ship adapting the Turkish author Sait Faik’s short story of the same name, which he proceeded to tow through the streets of Istanbul as part of a video artwork, compelling witnesses to grasp the historic Grecian adventure that runs clear through the largest Turkish metropolis.

For his current show, “Jpeg Archipelago,” Cosentino crafted a new ship out of a tin, titled, “Aura Boat.” His choice of materials, namely tin, derives from his insatiable urban explorations throughout Istanbul, in which he has observed the versatility of the pliable metal as a container for all of the staples of Turkish cuisine, like oil, cheese, or olives, and after its recycling when filled with concrete to regulate parking or soil to cultivate garden plants.

Cartography of alteration

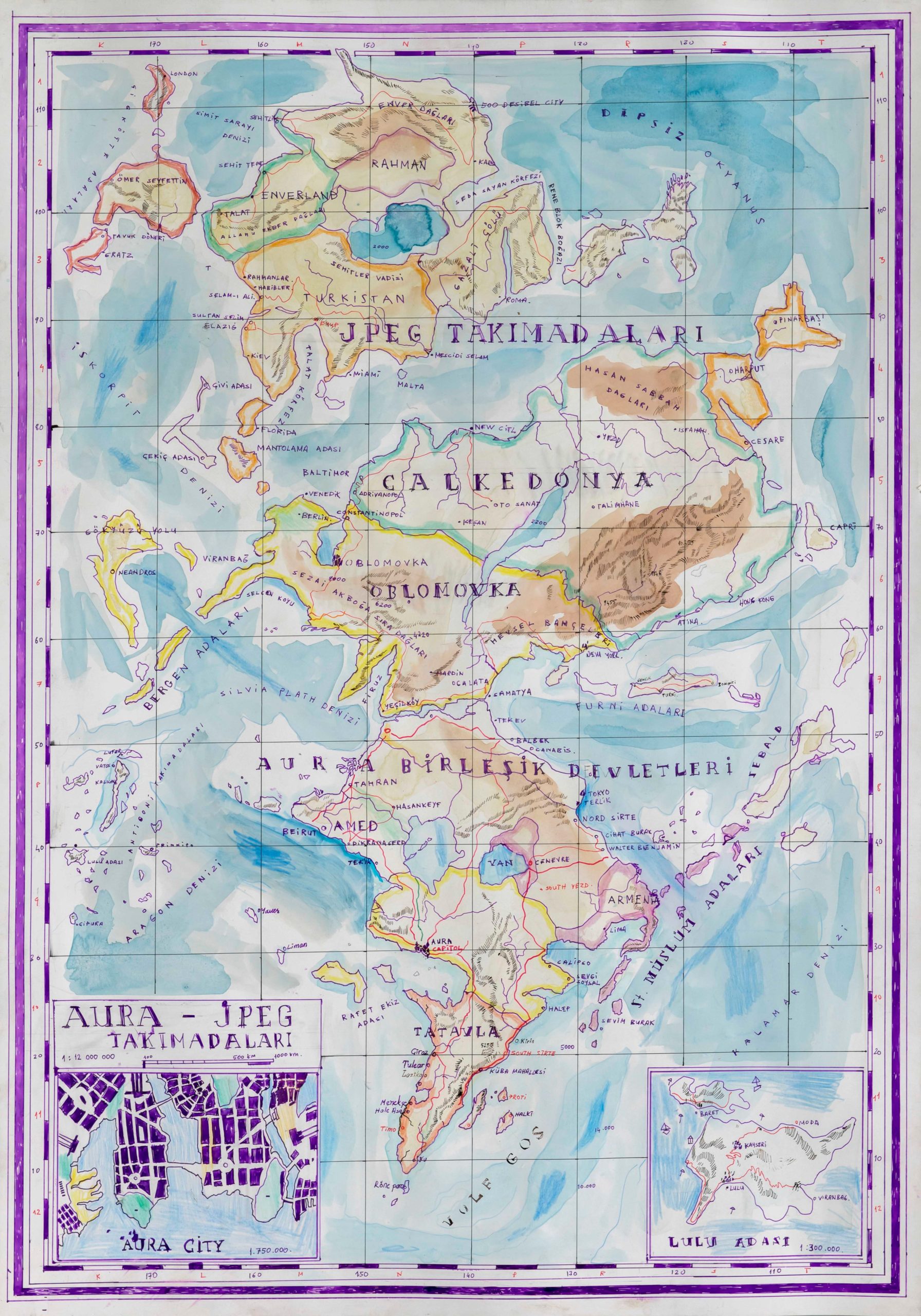

“Jpeg Archipelago” revolves around a curious map, the title artwork drawn by Cosentino to reflect a most unprecedented adaptation of the known world. His lands and seas are a mashup of displaced cities, in which the history of borders is rewritten according to a geography all his own. The fantasies of J.R.R. Tolkien come to mind in popular fiction, but Cosentino has not exactly drawn names from neologisms of philological invention.

London, for example, in “Jpeg Archipelago,” is, in Cosentino’s cheeky brand of humor, part of the “Çiğ Köfte Adalar” (Raw Meatball Islands), a dot on an outlying territory. A local incarnation of the approach to recreating global history from the ground up was shown during the 16th Istanbul Biennial, with the work of Norman Daly, “The Civilization of Llhuros.” But whereas artists like Daly have copied the museological model, Consentino is more artistic.

The installation of the 16 artworks that make up “Jpeg Archipelago” is immersive, offering its seers a liminal region of fancy in which they are caught between two lands, namely, Aura, a more favorable destination compared to “Jpeg Archipelago,” which in Cosentino’s map, is strewn with locations like “500 Decibel City,” or “Enverland,” etymological fabrications that might connote backward development, something akin to the global north and south.

The polished flooring of Zilberman Gallery transforms into the still waters of a sea in the frame of Cosentino’s exhibition. One artwork, a series of wood and ceramic sculptures titled, “August” (2020), figures a lady swimming up to her neck in the fictitious marine environment. Against the wall, paintings hang to represent the horizon. A canvas titled “Island” (2020) appears as from a night scene, capturing the ambiguity of both coming and going at once.

“I’m in the space, I feel the air surrounding me, it is a weird place. I don’t know how I came here. But I’m here. I will stay here for some time,” wrote Cosentino for a booklet accompanying the show, as his creative process often begins with a bout of creative writing before painting or sculpting for his multivalent installations and performances. “There is only one way out, to go to Jpeg Archipelago.”

Way out from inside

Cosentino is himself a traveler. His works, even in a gallery setting, are suffused with a sense of movement, driven by plot and character. To appreciate his installations brings about an experience that is both like reading a novel and watching a film, or a play. Visual cues are everywhere. The contemporary art medium through which he tells stories instigates active creative seeing, as he spreads the contagious inspiration that he catches everywhere

he goes.

With the talent of a stage designer, a distinctive eye for lighting is one of the elements that make a Cosentino exhibition special. His vibrant, varicolored illuminations have animated Istanbul’s many neighborhood galleries throughout the years, such as at Öktem Aykut in 2018, during the citywide “Large Meadow” summer exhibition organized by Riverrun. His tin sculptures have a Constructivist edge, melding street art, architectural modeling and city planning.

Despite works like, “Basketball Court” (2016), a relatively plain miniature reconstruction of its title subject, there are underlying subconscious metaphors and philosophical inquiries aplenty in “Jpeg Archipelago.”

In the curatorial text prepared by Zilberman, a famous essay by Walter Benjamin is referenced, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Production” in which the immortalized critic identifies artistic quality within the zeitgeist of industrial modernism.

“In principle, a work of art has always been reproducible. Manmade artifacts could always be imitated by men,” wrote Benjamin from the 1935 translation by educator Harry Zohn. “One might subsume the eliminated element in the term ‘aura’ and go on to say: that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art. This is a symptomatic process whose significance points beyond the realm of art.”

Interestingly, when Benjamin uses the term “aura” to define the essence of an artwork, he intersects with Cosentino’s latest revitalization of creative production as present within a perennial state of media res, that is, of process-based becoming, symbolized by the recurrence of a visual personality who leaps from canvas to sculpture to the idea in the imagined field of the “Jpeg Archipelago” installation.

With his pithy turns of phrase, Benjamin’s essay remains timely in an age when pandemic isolation is forcing art further into mechanical digitization. “By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence,” he wrote of original artwork as a cultural fixture in the face of technology. “And in permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced.”

Last Updated on Apr 06, 2020 3:50 pm

Discussion about this post