What do we really know about the digital world we inhabit?

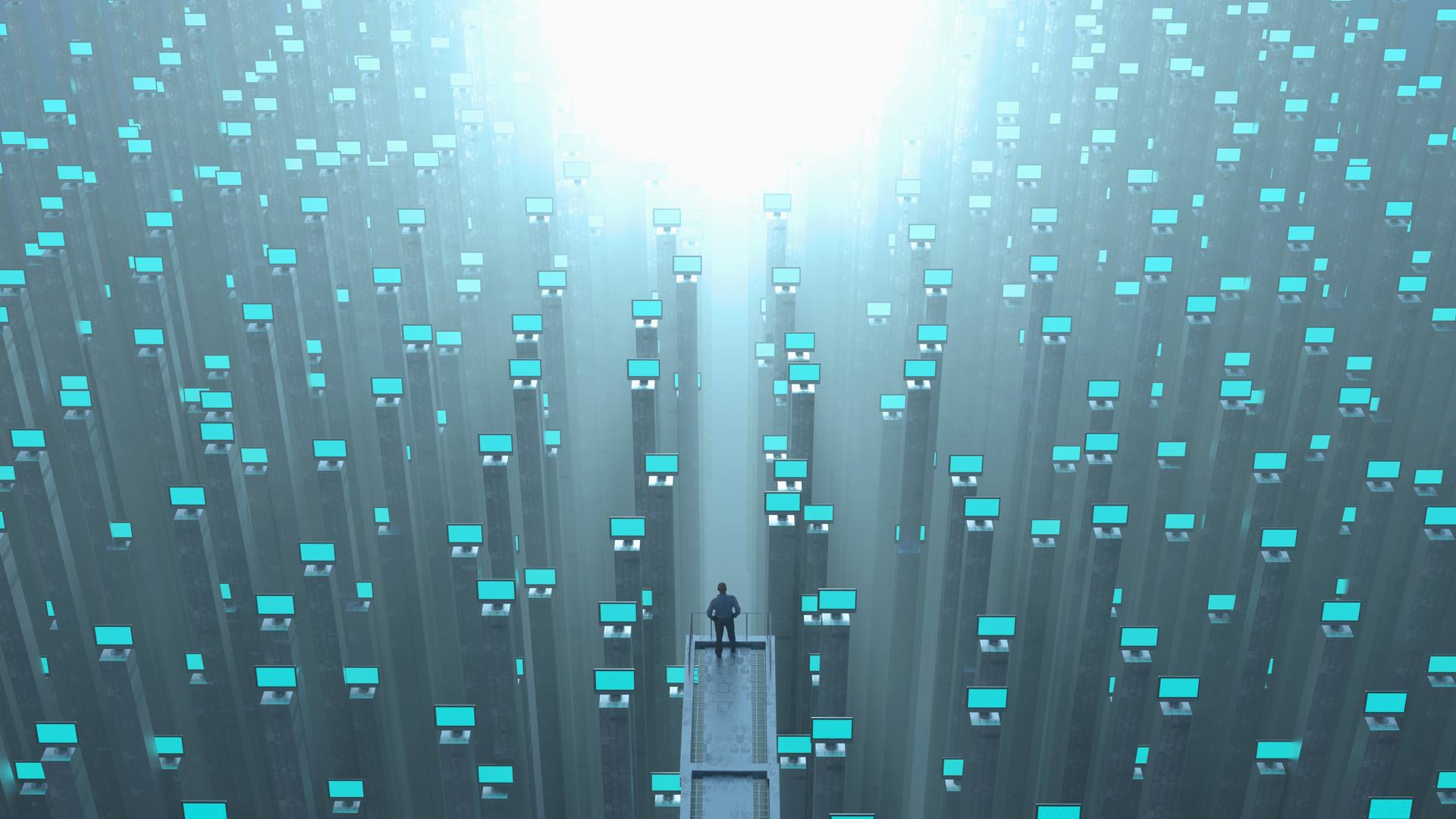

As the world around us increases in technological complexity, our understanding of it diminishes. Underlying this trend is a single idea: the belief that our existence is understandable through code, and better data will help us build a better world.

In reality, however, it seems like we are lost in a sea of information, divided by fundamentalism, simplistic narratives, conspiracy theories, and post-factual politics.

Given the libertarian utopianism behind the digital revolution, how did we end up in the era of ‘fake news’, algorithmic filters and surveillance capitalism? Is technology itself to blame or our relationship with it?

Fake Worlds

In his docu-film HyperNormalisation, Adam Curtis outlines how an army of technocrats, complacent radicals and tech entrepreneurs have conspired to create an unreal world; one whose comforting details blind us to its inauthenticity. Within this world emerged a constellation of immersive technologies: wielding tools of manipulation in service of cyber-capitalism, as its algorithms trap us in a cesspool of narcissistic oblivion.

Reality is now simulated; synthetic conditions that are generated seem more “real” than the actual experiential act, what cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard called “hyper-reality”.

At the heart of this is the notion that our contemporary experience is devoid of equilibrium. Artificial environments of learning, mobile devices, and interface VR or entertainment systems of communication and visual-sound displays have begun to reshape our perceptions and limbic systems in ways we are yet to grasp intelligibly.

Knowledge has replaced manufacturing as the most advanced mode of economic production, and data is the oil that greases our new silicon-fueled economies. New media exemplifies a profound fragmentation with its myriad streams of content, and when compounded with the disorientation of globalisation, has inverted reality into the sphere of the incomprehensible.

A departure into techno-fantasies is woven with insecurity: in the face of economic and social turmoil, we have fled to a more secure, wistful past on our screens.

This nostalgic drive expresses itself most powerfully on web 2.0 technologies. As populist contenders arise from the breakdown of existing economic and political arrangements, they have been largely successful in harnessing the power of social media to reach wider and more varied audiences than ever before.

Filtering Dissent

New media’s business model compels digital platforms to accumulate users, foster sociality and popularity through filtering algorithms that maximise attention and retention, generate a social currency of engagement and approval, and ultimately boost advertising profits.

Going viral is the Holy Grail.

Given the democratic principles at the core of the Internet, ‘trending’ parades as a cybernetic equivalent of the American Dream in a sprawling marketplace of eyeballs. As the corporate media’s concentrated spectacle is transmitted via the diffused spectacle of social media, the ‘narrowcasting’ of content in many ways intensifies the docility of consumers.

The governing protocols of interactive technologies present us with new dilemmas. Social media generates what Henry Jenkins describes as “affective economies,” in which users find legibility, or connectedness, through diverse emotional registers.

If legibility is contingent upon messages resonating at a particular frequency, then dissent becomes incompatible within the format; deviation cannot be tolerated because of how communities have come to discipline themselves.

Furthermore, there is an inherent vulgarisation of discourse that incentivises convergence over divergence – participation is predicated upon accruing attention and approval, insofar as there is unchallenged congruity of thought.

The correlation between the ability of consumers to filter their information by choice with the growth of echo chambers, while not wrong, is overstated. Less deliberated, is the individual’s automated extrapolation by algorithmic filters.

Public discourse is increasingly mediated by proprietary software systems owned by a handful of major corporations (Facebook, Google), which run filtering algorithms to determine what information is displayed to users on their ‘feeds’. Far from being neutral and objective, these algorithms are powerful intermediaries that prioritise certain voices over others.

Upworthy co-founder Eli Pariser uses the term “filter bubble” to describe this phenomenon of narrowcasting on social media, which he attributes to the “personalisation algorithms” imposed by companies like Facebook and Google that end up deepening seclusion from contrasting viewpoints.

Take the lead up to the 2016 US presidential election, which saw a proliferation of echo chambers on social platforms, as users limited to their own information bubbles were easy marks for misinformation campaigns.

The source of these ‘bubbles’ on social media is a combination of specific filtering logics that have become predominant – especially those of similarity and social ties, which structurally reduce diversity by design.

Meanwhile, a thwarted agency under neoliberal atomisation – a fetishisation of the individual detached from society – feeds a source of frustrated volition; a sense where our work is meaningless and elections don’t matter. To seek a way out of self-paralysis and feel animated, we overcompensate with outrage. New technologies incentivise this by offering everyone, at virtually any given moment, a platform to express indignation.

Through the currency of outrage, people can communicate their sensitivity to injustice through moralism culminating in today’s ‘age of outrage’. However, this discourse has been weaponised online as more of a vanity project, rather than attempting to identify problems and fix them in good faith.

‘Call-out’ culture, righteous grandstanding and public shaming are symptoms of a politics of defeat, as our (paradoxically) alienating social media platforms exacerbate tribalism and antagonistic speech to maximum effect.

Outrage can be mobilised constructively as the #MeToo movement has shown, identifying and calling out offenders has resulted in moving the cultural needle on matters of sexual assault and harassment.

‘Post-Truth’ Vortex

In a period of ascendant ethnocentrisms and authoritarian impulses, a ‘post-truth’ universe has become affixed to our turbulent socio-political landscape. Instead of ushering a new age where access to the truth becomes progressively democratised, the digital revolution – in its filtering of dissent – has facilitated half-baked beliefs to spread like wildfire into an ever-expanding cascade of disinformation.

The maxim “there are no facts, only interpretations” is warped into something of a postmodern platitude, whereby events that transpire are merely narratives to be inferred through a subjective lens. Lies can effectively masquerade as “alternative points of view,” as harmonious tones are amplified and transmissions that solicit dissonance are drowned out.

Hence, “facts possess a liberal bias,” and Kremlin propagandist-in-chief Dmitry Kiselyov can declare, “there is no such thing as objective reporting.”

On the surface, an old formula of slick, duplicitous stage management by the ruling class is not novel in itself. Politicians have always spouted falsehoods and cynically manoeuvred to preserve their interests. What distinguishes our epoch is a consensus responsible for manufacturing and maintaining consent – the technocratic urge to ‘fact check’ – was rendered impotent following the 2007-08 financial crisis, which ruptured the public’s faith in expertise, institutions and status-quo politics.

As a result, faith in conventional techniques for gauging reality (i.e., ‘facts’) has waned.

In this context, ‘fake news’ is but a symptom of our information ecologies responding to fractures in big media’s monopoly over content. A wellspring of ‘alternative media’ outlets have benefited from these communicative fissures, exploiting new technologies and old techniques to compete on the plane of truth-telling.

The rise and fall of ‘alt-right’ provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos illustrates just how fickle this new post-truth media landscape can be: from over 330,000 followers on Twitter to losing out on a book deal and being subsequently de-platformed, banned and blacklisted from mainstream broadcasting, and now broke.

Similar episodes with notorious far-right figures like Alex Jones and Tommy Robinson show just how easily one can build an online presence and profit from disinformation, and how quickly that reach can be taken away by de-platforming methods on those same new media outlets.

Embracing Complexity and the Unknown

In New Dark Age, James Bridle suggests that at the core of our thinking about technology lies a purblind faith: we simultaneously model our minds on the understanding of computers and believe that – if we supply them with enough data – they can solve all our problems.

Indeed, as the cybernetic realm has ushered in the colonisation of everyday life by information processing, we have come to accept the notion that everything is essentially computable.

But technology is not neutral. It embodies our politics and biases, and supersedes national borders and, at times, even its creators. While potentially anarchic and liberating, it is susceptible to capture by existing power structures. Information breeds overload and false certainty, leaving us to comprehend less about the world as powerful technologies garner more control over our everyday lives, as our social and political arrangements wallow in decay.

From the erosion of the nation-state, the triumph of transnational corporations, totalising global surveillance, environmental degradation, to rising inequality – while none of these are a direct result of new technologies, they are all a product of what Bridle regards as a failure to “perceive the wider networked effects of individual and corporate actions accelerated by opaque, technologically augmented complexity”. This opacity is deeply political, as it obscures the mechanics of power.

Yet Bridle doesn’t want to assert, as is frequently espoused, that ours is a period exceptionally confused by modernity – instead, just a new manifestation of it. Part of the reason for feeling that we inhabit an age that is increasingly unknowable is because more of the world is being organised by and for machines than by human beings.

Furthermore, our grasp of technology cannot be limited to a functional and pro-market perspective (“learn to code!”). Bridle claims that we need to know not only how things work, but “how things came to be, and how they continue to function in the world in ways that are often invisible and interwoven. What is required is not understanding, but literacy.”

What might be a solution? In our struggle to conceive of the scale of new technologies, Bridle believes in forwarding a non-data vision of reality, in which we are comfortable grappling with complexity – a “cloudy thinking” that embraces the unknown – as he argues.

This echoes philosopher Georges Bataille’s concept of “nonknowledge,” which states that the creation of knowledge entails a corresponding creation of new fields of ignorance. The expansion of information does not only produce answers to questions; it also spawns new unknowns and possibilities.

As Bridle affirms, “our technologies are extensions of ourselves, codified in machines and infrastructures, in frameworks of knowledge and action. Computers are not here to give us all the answers, but to allow us to put new questions, in new ways, to the universe.”

For, pregnant within these “radical technologies” as Adam Greenfield calls it, is the potential to usher in enormous changes that lead to very different futures: be it a “fully automated luxury communism” or a dystopian surveillance state and capitulation to networks of autonomous supercomputers.

New technology has raised the spectre that the machines we’ve invented will eventually replace what elevated humans from the rest of the animal kingdom: our intelligence. The hegemony of big data and computational thinking has had the curious effect of magnifying those perceived threats.

What is clear is that power and politics are at the heart of our algorithmic unease. The concern is that emergent networks of intelligence that we do not yet understand operate towards malevolent ends, and how we combat it will necessarily involve embracing complexity and the unknowable – while building differentiated and complimentary relationships between human and non-human intelligence.

Author: Amar Diwakar

Amar Diwakar is an independent writer and researcher. He has written for Al Jazeera English, The Boston Globe, In These Times, and other publications.

Source

Discussion about this post