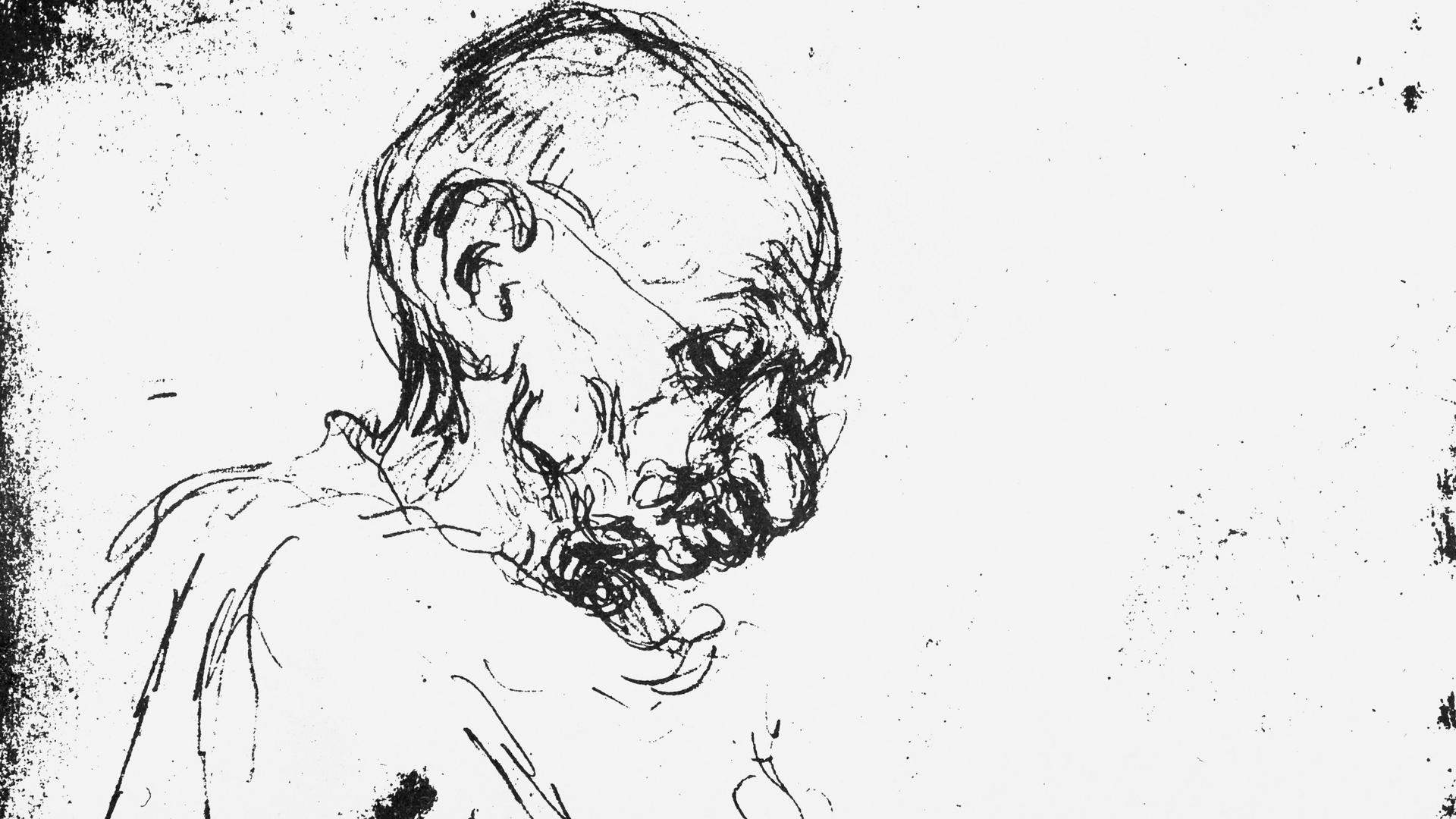

Mahatma Gandhi is symbolically everpresent in India, but much of what he stood for is now lost.

It is difficult to guess what United States President Donald Trump had in mind when he recently described Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi as the “Father of India.” But he achieved one thing: further trivialising an already diluted sobriquet ascribed to the country’s legendary leader Mahatma Gandhi.

You cannot miss him. Gandhi is everywhere in India – from currency notes to main roads that run through major cities, to statues sprinkled across the vast nation and various government programmes with his name on them. On his 150th birthday today, there is no reason to fear his name getting obliterated, but one cannot be so sure that his legacy will survive.

Gandhi looks like he will remain in the memory of the Subcontinent for a long time, but what he stood for is receding at a supersonic speed that India can afford only at its peril.

Take for instance, the fraught relations between the majority Hindu and the minority Muslim community. Gandhi fought all his life of cordial ties between the two, went on hunger-strikes to stop rioting among them and finally in 1948, a year after independence, fell prey to a Hindu right-wing nationalist assassin, Nathuram Godse, who was unable to tolerate his liberal, inclusive ideas and support for the Muslim community.

It is not that there have been no riots since his death. On the contrary, there have been innumerable instances of violent riots between the two communities leading to scores of deaths.

During his lifetime even Gandhi—despite his firm views on non-violence and peaceful inter-communal relations—found it difficult to douse the animosity that existed among the two communities. He was particularly devastated at the bloody riots that marked the partition of British India into independent India and Pakistan.

His assassination too did not help, and in independent India, violence between sections of Hindus and Muslims continued sporadically across parts of the country. Though riots of that nature have fallen in number in recent times, what has not improved is the deep prejudice that exists between the two communities. And now, paradoxically, right-wing nationalist Hindu groups led by the RSS and its political affiliate, the BJP are in power.

Riots have come down, but the animosity has taken the character of majoritarian domination that is visible in several ways – most notably cases of lynching that have left the nation reeling at the lawlessness and audacity.

In a country where someone like Gandhi stood for non-violence, the vigilante mobs led by radical Hindu groups have targeted hapless Muslims leading to deaths and serious injuries.

What is more shocking is that the state machinery does not seem to have responded reasonably to these attacks. Rarely have the culprits been penalised and, more often than not, been freed. In one instance, a federal minister Jayant Sinha even greeted the suspected attackers who had been let out on bail.

One would expect the sharp differences between the communities to soften with time as inter-community marriages become more common. But, increasingly, it has become challenging for a boy and a girl from the Hindu and Muslim communities to marry one another.

Vigilante groups call it “love jihad” and view it as a conspiracy to undermine their religion. Both Hindu and Muslim radical groups are complicit in the violence that is unleashed on such couples.

Gandhi, who stood against inter-caste animosity, would have cringed if he had been alive today, seeing the unravelling of everything he stood and fought for so admirably.

Despite the passage of 72 years since independence, atrocities committed on underprivileged castes have continued without a break. It is relatively routine to come across cases of so-called honour-killing, where parents don’t even spare their children if they marry someone from a caste lower than theirs. In many cases, young Indians who dare to go against the diktat of their families on this issue have been killed mercilessly.

Gandhi’s vision of a decentralised, village-centric economy has long been forgotten. Since the 1990s, when economic reforms were undertaken, the movement towards big, urban-centric industrial growth has increased exponentially. So much so, today’s Indian villages are largely empty and millions of families have migrated to the cities in search of jobs and livelihood.

The recent move by India’s federal government to rescind special status to Kashmir is another issue that Gandhi would have opposed. For, in all the moves, including the incorporation of this legislation (Article 370) in the Indian Constitution, Gandhi was in the know and in agreement.

Now to see it struck off and witnessing Kashmir in a siege-type situation would have upset him. As a well known Gandhian, 102-year-old H S Doreswamy was quoted as saying in The Hindu newspaper, “Gandhi would have launched a satyagraha (peaceful protest) against the abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir.”

The point then is, where does India stand vis-a-vis Gandhi’s legacy?

The Gandhi revered not just in India, but all over the world for his innovative resistance to colonial domination has been reduced to a caricature in the country of his birth. In fact, since the advent of the Modi government, some individuals affiliated to the ruling BJP and right-wing groups have started idolising Gandhi’s assassin Godse with the barely concealed motive of rewriting history and justify the killing.

Meanwhile, the Indian nation goes ahead celebrating mechanically its most treasured icon with holidays declared across the country, politicians including those from the right mouthing ‘nice’ things about him, Prime Minister Modi writing a piece on him in the New York Times while small civil society groups chant the hymns and songs popularised by Gandhi during the freedom struggle.

Tomorrow, it is back to square one. Gandhi will return to his post in photos, currency notes, statues and the various other memorabilia – immobilised and helpless.

If Gandhi were asked about Trump’s anointment of Modi as the new “father of India,” he would probably agree to give up the title and hand it over to the prime minister as he may see no reason to continue being the father of a nation he can no longer identify with.

Author: K S Dakshina Murthy

The writer is Associate Editor of the India-based news website www.thefederal.com

Source

Discussion about this post