In the academic literature on international relations one of the key concepts is soft power. No matter whether it is a capacity at the disposal of states or a contextual relationship demonstrating the ability of one actor to have an influence on the identity, interests or behaviors of another through the employment of non-coercive instruments, the consensus view is that soft power does emanate from the attractiveness of one actor’s values, policies and institutions in the eyes of others. Whether it is positional, contextual or relational, soft power springs from unintentional state or societal activities automatically in a bottom-up manner. Whereas hard power can be seen, observed and measured, soft power is hard to detect and measure. Whereas hard power is put into use by its practitioners intentionally, soft power is something in the air and in this sense much closer to latent, institutional or structural power.

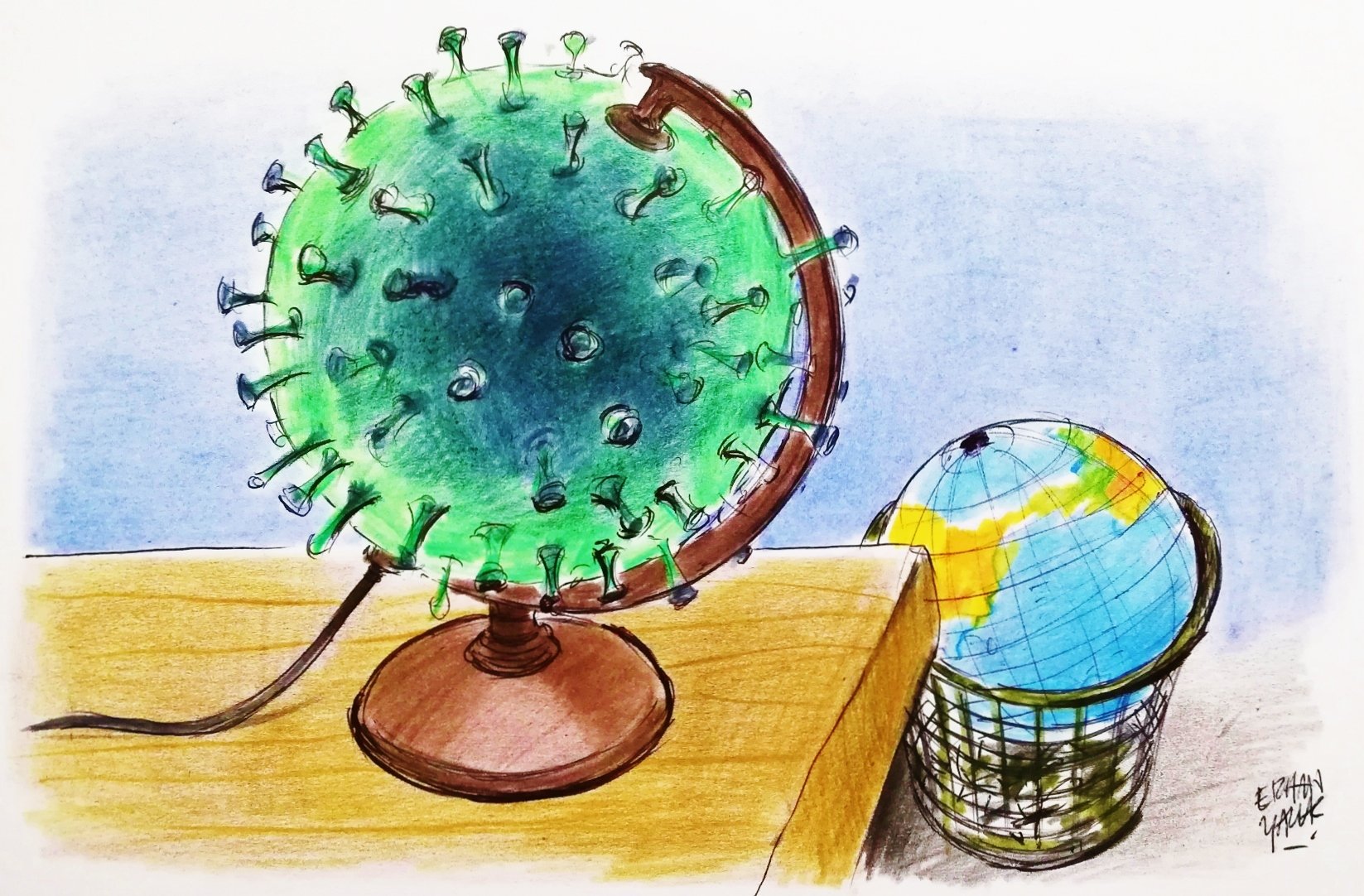

This was then. As we are now fast moving to the post COVID-19 era, soft power is losing its innocence and increasingly being defined as an ingredient in the toolkit of great powers. The more soft power is seen as something that needs to be manufactured in a strategic manner, the closer it comes to sharp power. I believe the years ahead will increasingly see soft power being mistakenly defined as sharp power and turn out to become a weapon at the hands of states, most notably great powers, to be employed in their geopolitical games.

Highlighting the line

In an era of great power competition, soft power cannot remain soft; it must transform into sharp power. Whereas soft power emanates from attraction, sharp power stems from cultivating a positive image about one’s self as well as activities of manipulation and disinformation targeting external audiences. Trying to cultivate a positive image about one’s self intentionally and strategically is not something wrong in itself, yet if you do it in such a way to gain further ground against your competitors and if manufacturing soft power activities paves the way for manipulation and disinformation, then the line between manufactured soft power and sharp power gets blurred and soft power increasingly becomes the penultimate stage before arriving at sharp power. When it becomes a tool to be employed in interstate competition, soft power can no longer be considered as soft or innocent nation-branding efforts.

I think this is the scene we have been increasingly witnessing over the last decade, and we will see more of it in the years to come. To test how it feels, just take a brief look at how Russia has been waging political warfare against liberal democracies in the aftermath of the Crimean crisis in 2014. There is a war between Russia and Western powers, and this war is being fought more politically than militarily. Apart from the ongoing proxy wars in Syria, Libya and other conflict-riven failed states, the growing power competition between Russia and liberal democracies has been evolving more in political than military platforms. Lending support to pro-Russian political parties and movements across Europe and the United States, helping manufacture a positive image about Russia and its policies through the employment of all available media platforms and resorting to disinformation campaigns with a view to tarnishing the image of the West all over the world can all be considered as textbook examples of how sharp power has increasingly become a part of Russian statecraft.

Investing in creating alternative truths and contesting conventional understanding of social realities constitute other examples of how sharp power is exercised. As universalism has begun giving way to relativism and as various practices of the globalization process have been increasingly replaced by various practices of protective nationalism in recent years, sharp power wars have inevitably turned out to be propaganda wars. It is undoubtedly clear that the shift from a U.S.-led unipolarity toward a contested multipolarity has eased this process.

After the coronavirus

I am of the view that this process will accelerate in the post COVID-19 age. The competition between the United States and China will intensify, and what will shape the end result of this growing competition will increasingly revolve around the question of how many followers China and the United States will each have in the following years. The two powers have already engaged in a propaganda war concerning the success of the measures each adopted to defeat the coronavirus.

The sad truth is that none of us is in any position to verify the authenticity and legitimacy of the narratives that American and Chinese governments radiate around the world. Should we name the coronavirus the Chinese virus as American President Donald Trump wants us to do? Is China helping others defeat the virus as a good international citizen, or is China’s mask diplomacy and financial assistance to needy countries aimed at salvaging China’s tarnished image in the early days of the pandemic? Is it the Chinese or American model of governance that performs better? What about the performance of the World Health Organization (WHO)? Has it actually transformed into the Chinese Health Organization as many China-bashers would have us believe, or are China’s increasing contributions to global governance, most notably in the realm of efforts to defeat global pandemics, what we need as Trump’s America is abdicating its global leadership and becoming more introverted each passing day?

What strikes me as a scholar of international relations is that it is becoming more and more difficult each passing day to assess the truth in the claims of any actor in any power competition. Objectivity is becoming increasingly contested. Multipolarity is aggravating this problem too, because as material power is dispersed among many actors, the number of alternative truths also multiply. In such an environment, it is going to become more difficult than ever to separate soft power from sharp power. As the power of attraction is considered to be more vital to the end result of various competitions across the globe, many will increasingly see it as way station to power of manipulation.

* Professor at the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Antalya Bilim University

Last Updated on Apr 27, 2020 4:29 pm

Discussion about this post